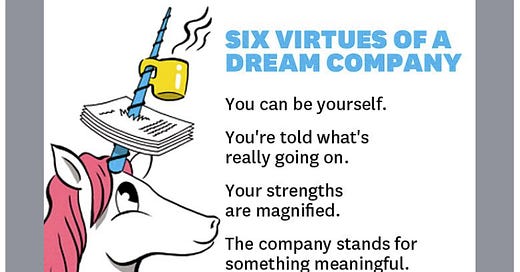

I recently ran across an insightful article, published a decade ago in Harvard Business Review (HBR), exhorting the virtues of a “dream company.” The authors interviewed hundreds of executives in reaching the ultimate conclusion that authenticity, more than any other quality, conjoins the cultural qualities most prevalent in engaged and positive workplaces.

Authenticity, in this context, means employees are able to behave freely as individuals, have honest communication with leaders and executives, enjoy genuine investment in their growth, expend discretionary effort because they believe intrinsically in what they are doing, and are relatively unhindered by red tape and bureaucratic control. The argument extends to say that creating this sort of engaged culture leads to better results.

I’ve certainly found these themes ring true in my own professional journey. When teammates are given honest insight into the circumstances of the larger organization, they can form stable expectations about the future and feel a sense of belonging and shared fate. These are feelings of safety. They lead to larger individual investment of time and energy and strong focus on the long term in favour of short-term gain-seeking.

Being honest with people is also a subtle but powerful form of advancing equality; if I share what I know with you, recognizing that not only can you “handle the truth” but you might actually provide insight and ideas that hadn’t occurred to me, I am in doing so treating you as an intellectual equal. I am recognizing that I’m no smarter than you even if I have more authority or status in the organization.

This can be a difficult behaviour for senior leaders who’ve reached their posts by exercising high intellect and judgement, developing masses of confidence over time which can impair humility. They can easily believe themselves smarter than anyone else in the room. But not only is honesty damned important to feelings of trust and empowerment within teams, having an open communication loop is critical to avoiding insularity and entropy in senior management circles. See Enron for an example of how a closed executive loop and a lack of intellectual humility can allow a company to persuade itself onto a catastrophic course.

But if this is all so clear and such a matter of common sense, why does it need to be encouraged? Why isn’t it just the norm and the accepted wisdom?

In a word: shareholders.

Successful companies grow bigger. Big companies go from being family-run and/or privately owned to being publicly traded. Investors buy shares in the company, thereby becoming its source of capital on the bet it will succeed and give them a return on their investment. This subjects the company to corporate governance by a board. While even the smallest companies exist to make money (often or perhaps usually, at least in the beginning, in addition to other motivations), the transition to board governance means that the company’s executives are now accountable to a third party — the shareholder — to maximize the company’s value. This is a fundamental shift in the value proposition for company leaders. Strong performance is no longer enough; they need to create strong performance in a way that increases share price.

While it’s an American myth that maximizing company value always and inescapably equates to maximizing shareholder value, there are powerful reasons why this mindset dominates big business boardrooms.

First is the disruption and complexity which can ensue when these motives are spliced apart. For example, a company learns that the manner in which it has been disposing of manufacturing by-products is polluting fresh water reserves in the local community. It has a choice between paying a nominal fine on a recurring basis or undertaking a massively expensive process redesign in order to be more responsible. If the former action will result in a higher share price than the latter, board members will feel pressure — if not an outright duty — to pay the fine and continue polluting, even if this offends the company’s value in other ways. And in fact, the company in this hypothetical, having made its decision to continue irresponsible behaviour, will then feel compelled to downplay or conceal its conduct, to include by forcing its own teams into lies and artifices by legally binding them into non-disclosure as a condition of employment.

This is one hypothetical example of an infinite ocean of conundrums which can accumulate into an unintended corporate culture which trades one form of value for another, over time becoming bottom-line obsessed at the expense of other principles.

But second, and perhaps more powerful, is the individual interests of board members themselves. Because board members and executives are compensated in ways tied closely to market performance, such as shares of company stock and/or bonuses and options tied to financial results, their interests and those of shareholders are tightly unified. It becomes strictly rational for a company executive to make a decision or support an option which will maximize share value, because this will also maximize value for the individual.

Creating a positive and engaging work environment for employees is not cheap. It means providing ample resources and staffing. It means investing heavily in recruitment, education, and development of individuals. It means leaders must invest their time in explaining decisions and must wrestle with the challenges they invite by being honest about policy, resource, and operational adjustments.

Many companies, if not most, start out by organizing themselves around principles which will attract and retain strong talent. This leads them in the direction of the six virtues and the culture of authenticity championed in the HBR article. And they tend to stick with these commitments as long as things are going well.

The tricky part is how companies react when things don’t go well. When shareholders start to lose value, boards face tough questions about the decision they’ve made. Investors can threaten to chuck out board members in favour of replacements who will make them more money. They can threaten and often initiate legal action which, even if it never culminates in a courtroom, can be costly and distracting while ratcheting up pressure to achieve share price improvement. Look no further than the Byzantine machinations of the wildly popular Succession for a telling heuristic.

To avoid all this, boards will do what they must to defend against it, to include posturing for shareholders with short-term cost controls. Reductions in resources, staffing, support, and compensation are typical signals of real or perceived investor pressure, and can be expected any time financial results fall below expectation. Operational cost controls also become more likely, and driving compliance with them means more policy, more red tape, more rules. Process and permission become proxies for conversation and latitude. And since upholding share price also means sparing senior executives their blushes, transparency about the source and rationale for unpopular decisions falls off drastically.

Suddenly there are fresh reasons to guard and control rather than release information, because release opens the possibility of varying interpretations of what is happening, and the open sharing of these interpretations can impact perceptions about company performance. Negative perceptions gnaw away at share price. Honesty and openness are thus diminished in favour of perception management. This means spin and influence as proxies for straight truths. As this form of communication becomes more prevalent inside an organization, dissonance begins to ring in the ears of employees, who become less and less certain of what is happening in their own company. Expectations become less stable, and an underlying hysteria can take hold, causing a loss of talent with those most principled the first to go for the exits.

Any organization is a complex amalgam of values and interests. When the two coincide, both will be vindicated by the organization’s behaviour. When they diverge, interests will win at the expense of values. And once a company begins to lie about itself, it then develops an interest in making that lie feel true. This compounds the dishonesty required to vindicate its interest. Authenticity is a predictable and early casualty.

This is but a modest and abstract glance at the well-trod path that carries many companies, though not all to be fair, distant from what they set out to be. And the cherry on top is that by leaving values at the side of the path over time, they become more financially successful. Which, in popular and practical judgment, simply means more successful.

And this is why the idea of a “dream company” is unintentionally spot-on. Such companies will remain the stuff of dreams, because in the end, the structure and system within which companies exist is not conducive to this wonderful ideal. They can’t achieve it and be successful as defined by the environment. And nor will it ever likely be the case, so we will continue dreaming dreams but living reality.

TC is an American management professional passionate about positive work experiences. He writes from Manchester, United Kingdom.