Amazon's Rank and Yank Talent Process

Forced distribution fuels dishonesty, coercion, and a "Hunger Games" mentality

In the 1980s, General Electric CEO Jack Welch sat in a quiet room, twisted his moustache, and with what must have been a thunderous belly laugh, concocted a talent management technique so frostbitten with rational calculus it would have made Machiavelli himself blush with envy.

Welch’s brainchild, “Rank and Yank,” became a widely-adopted tool in large corporations over the next few decades.

Rank and Yank guides talent assessments through a 3-step process:

Rank every salaried employee’s job performance 1 through n. Do this at every level within each node of the organization.

Use the rank-ordered list to identify a bottom segment of performers, usually 10% but perhaps more or less.

Fire those in the bottom segment.

Survivors then have their compensation and career progression calibrated according to where they fell in the rating curve.

With this approach, employees are not evaluated according to the results they’ve delivered or their performance vs. expectations communicated to them. This means an individual can do more than expected of them, be considered a strong performer, and still get fired.

And because employees are rated against one another in a gambit for professional survival, Rank and Yank is an inherently cut-throat method known to instigate unhealthy competition and negative work cultures.

These and other liabilities led most businesses to abandon Rank and Yank over the years in favor of more humane and sensible methods of differentiating performance.

But a few companies persisted in using it. One was Enron, which went defunct after its normalized toxicity spilled over into broad-based dishonesty, arrogance, and criminal fraud.

Another, Amazon, continues to use Rank and Yank to this day. And the reasons for doing so echo those attached to Jack Welch’s original conception nearly a half century ago.

Fear as motivation.

Creation of a compliant workforce.

Low-cost generation of discretionary effort.

We should discuss each of these in a bit more detail.

But before we do that, I will acknowledge variance between what I have just said and Amazon’s official position.

Amazon doesn’t admit to employing Rank and Yank, and if it did stipulate, would slap a much more digestible label on it.

There are indeed some differences between the unashamedly draconian Welch/Enron versions of years gone by and Amazon’s evolved, better cloaked version.

To make Rank and Yank more palatable, Amazon adorns it in the garb of continuous performance improvement, ornaments it with comforting claims about it being a common industry practice, and seals it with the credibility of a globally consequential retailer and massive employer.

This is an attempt to decouple its talent process from forced attrition through the employment of two ingenious artifices.

The company does not attach attrition targets to the talent assessment process. They are implicit by the imposition of a curve which insists that a certain percentage of salaried employees be declared “Least Effective” (LE). But by removing any mention of attrition from reviews, Amazon achieves a degree of inferential separation.

Those in the LE category are not summarily fired. They’re entered into performance management plans which purport to afford them an opportunity to improve. In the vast majority of cases, LE is the beginning of a path out of the company. But by inserting a process between designation and sacking, Amazon affords itself conceptual distance from openly caustic labor management practices.

But make no mistake. When you peel away its exaggerated exterior, you find the same charred, festering, vampiric heart pumping sludge into the veins of a coercive and misery-inducing process.

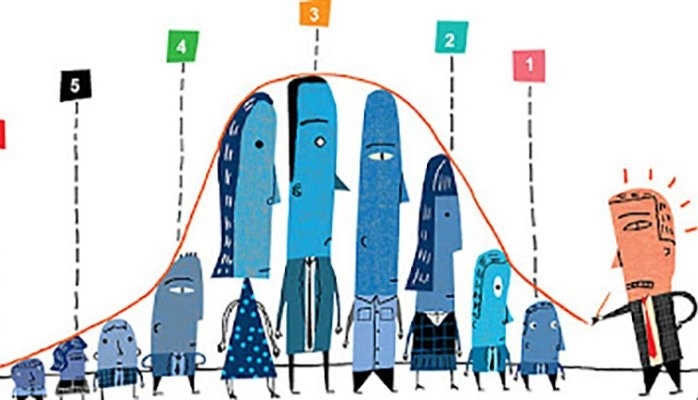

It doesn’t have winners and losers. It has survivors and victims. Everyone is ranked. A talent curve is overlaid onto that ranked list. Those at the bottom are hunted and eventually perish, with few exceptions.

In my 7.5 years at Amazon, I never met a single individual who thought forcing a talent curve was a good idea. I never met anyone who felt it was consonant with Amazon’s leadership principles.

General Managers hated it the most, because the imposition of talent ratings upon their teams by someone who didn’t know or work with their people was a fundamental boundary violation. A burglary of their authority commonly responsible for undermining relationships and team cultures they’d worked tirelessly to build.

But never mind everyone hating it. Year after year, we would bitch about it. Challenge it. Employ data, evidence, logic, and principle to question it. And year after year, we would be ignored.

There are reasons Amazon sticks with it, and we’re seeing some of those reasons stick out as more prominent cultural features of the company over the past couple of years.

Let’s visit them again with a few vignettes. Each of these is modeled on an actual situation I observed indirectly during my Amazon tenure, though I have bent and sanitized them enough to protect identities.

Fear as Motivation

Phil McCracken is a senior ops manager running a safe and successful outbound operation in an Amazon warehouse. After a solid year of performance, his GM gives him feedback that he has met a high performance bar. Phil then learns that his close colleague, John Coctosten, has been put onto a performance plan and is likely to lose his job. This sends an unwelcome chill down Phil’s spine.

Phil and John have very similar performance profiles, experience, and results. Both are similarly regarded by regional leadership. When John is offered severance and let go a few weeks later, Phil is consumed with fear. He knows he must not have been too far above John in talent review.

With John now gone, will he be next? Over the next year, Phil puts in 10-15 more hours every week, sacrificing personal and social time. Beneath a calm exterior, he is swimming with stress and coping through bad habits. He oversubscribes to work, further degrading his health and relationships. He becomes more notorious in pointing out his own contributions and less celebratory of his peers.

Phil is protecting his job out of fear. Not the fear that he might under-perform. He knows he is great at his job. But the fear his work might not be understood or appreciated, or that despite his best efforts, he might be deemed the slowest gazelle at talent review.

Mark Twain said “nothing so focuses the mind as the prospect of being hanged.” Amazon has co-opted this grim logic and injected into talent management.

Creation of a Compliant Workforce

Lilly White is an Amazon GM. Among her senior managers, she has no weak performers, having rehabilitated a previous struggler and managed a serial under-performer out of the company in the past year. At talent review, she finds herself in a fight to keep one of her senior ops managers, Phil McCracken, out of LE. He’s been a solid performer, delivered above expectation, and has run the safest and most productive outbound department in the region, fulfilling more than $800M in Amazon revenue.

But Phil hasn’t been involved in any high-profile projects. He’s not as active in promoting himself or establishing his profile. Phil’s moral courage and integrity compel him to challenge regional leaders more often than peers, and his honesty lends to a blunt communication style. He has fallen out of favor with the regional director over a few disagreements. As talent review unfolds and the group find themselves forced to choose one more LE at his level, Phil ends up designated, over Lilly’s passionate objections.

Lilly places Phil into an improvement plan which is totally pro forma. She does her best to stitch together some goals which can help Phil improve, but she doesn’t see a lot of opportunity and has to stretch to come up with much. After four weeks of observation, she concludes Phil has met his objectives and no longer requires additional support. She removes Phil from the plan.

When she tells her regional ops and HR directors, they immediately schedule a call to discuss it with her. On that call, she finds her judgement questioned, along with her integrity. She’s asked to prove and justify why she took Phil off the plan rather than continue to manage him out of Amazon. Insulted, she harbors resentment but gets her head down and focuses on her role, delivering a marvelous Prime Day and topping the performance scorecard for her region.

After third quarter talent review comes and goes, Lilly is pulled into a call where she is told she herself is now going onto a performance plan. Her failure to be “tough enough” on her “under-performing” senior ops manager is the reason. The plan was used as punishment for failing to comply. Never mind that doing so would have forced Lilly to make one of her direct reports jobless for reasons she felt were dishonest and wrong.

Rank and Yank provides an entire playing field for the issuance and enforcement of executive fiat. It’s a recurring reminder of who is in charge and how authority works. While Amazon pretends that managers are encouraged to disagree with superiors and pretends they retain the authority to make their own management decisions, some of the most important decisions impacting their teams are out of their hands. Talent designations drive pay, promotion, and job security. And decisions about them are often not made by actual line managers. Instead, they’re made at executive level and enforced at the point of a career bayonet.

This turns talent reviews into compliance machines.

Low-Cost Generation of Discretionary Effort

Charlotte Webb is an HR manager for an Amazon warehouse. She does superb work, is experienced, and expertly manages her team. As talent review approaches, she expects a good result and a promotion to the next level. Having proved herself convincingly at current level over the past several years, she has nothing left to prove.

Or so she reasonably believes.

After talent review, her boss tells her she is “getting close,” but still needs to convince a few stakeholders. It’s suggested she volunteer to expand her role and lead two warehouses simultaneously in the coming year as a way to eliminate any doubts. Eager to prove herself and secure a valuable promotion, she tells her family things are going to be busier for a while. She volunteers, expands her role, and finds herself working twice as hard for the same salary.

Reflecting with her husband one evening after a few glasses of wine, it dawns on Charlotte that the job she’s doing is meant for someone at the next level. She’s been tricked into doing it without the promotion, in order to earn the promotion. Nonetheless, having committed to a path, she sticks with it and spends the rest of the year pulling double duty.

This is common practice in Amazon and comes in myriad forms and configurations. And it’s a completely deliberate and manipulative form of cost savings.

As a work environment, operations requires everyone giving everything they’ve got at all times. If everyone does the minimum required, the operation fails. But if everyone gives the most they can, success follows.

There are two ways to unlock discretionary effort.

The right way, the lasting way, the positive way, is to inspire teams and take care of them. Provide material support. Keep them safe physically and psychologically. Provide strong leadership, recognition, and pay. Then get out of the way. This approach requires resource investment in developing strong leaders. It trades an efficiency model for a relationship-driven model, and in doing so embraces the messy non-linearity of human performance.

The wrong way, the perishable way, the cheap way, is to dangle carrots in front of them and hoodwink them into a perpetual chase where they give more than is fair or reasonable to expect.

Talent reviews at Amazon are carrot factories, and the path to legalized usury. Driven by cynicism, they extract a margin of extra-contractual value while pretending to do their victims a favor.

I don’t know about you, but that does not sound like the behavior of “Earth’s Best Employer” to me.

Rank and Yank is not really a talent device. It is a control device. The design is to control behavior, coerce employees, and keep them on the psychic defensive.

Whatever arguments might be made in favor of this talent approach, a single fact defeats them all and should make companies like Amazon shed this decrepit practice.

That fact is that Rank and Yank results in individuals being given inaccurate performance ratings. Fitting a curve by rating people against one another presumes a fixed percentage of under-performance. When this percentage is wrong, which is pretty much always, someone is given a dishonest rating.

When dishonest ratings impact things like pay, promotion, and job security, the result is not just pathological, but outright toxic.

The inherent dishonesty alone should be enough reason for Amazon to kill Rank and Yank, even if nothing else I have argued is accepted.

But I doubt anything I have written here comes as a surprise to Amazon’s executives or their HR advisors. As I’ve argued, I suspect they cling to Rank and Yank because it serves interests of cost control, compliance, and coercion.

I wouldn’t have made these arguments a few years ago. But what Amazon has been demonstrating to us recently is that it doesn’t view its people as people, but as units of production to be squeezed, sweated, and optimized like machinery.

When your mindset dehumanizes labor in this way, empathy and emotional intelligence are not prevalent. They are replaced by short-termism and profit obsession.

And in that sort of culture, Amazon’s version of Rank and Yank fits just perfectly.

TC is an independent writer and speaker on organizational leadership. He has more than 30 years of leadership experience, including military command and director-level roles in commercial operations.

Well written and put. I also personally witnessed and experienced all of this, and more, during my time in Amazon operations and HR. Keep shining the light on these dark corners.

Missed one important thing. GM implemented rank and yank because they were secretly on the edge of bankruptcy. They managed to distract from their financial troubles through laying off the bottom 10% every year for longer than they should have been able to manage.