But I Digress

Timeless wit and wisdom from an American everyman

I.

When I was about ten, I sat in the back of our family car with my brother while our Dad took us through the McDonald’s drive-thru. This was before AI-assisted or app-based ordering. You had to talk to a human, usually a teenager or parolee, sometimes a teenage parolee. Someone doing a shit job for a shit wage while taking shit off everyone and wearing the shittiest work uniform in the history of work or uniforms.

On this occasion, Father Carr was preoccupied with pickles. He carefully explained to the teenage parolee that he didn’t want any pickles on his Big Mac. He explained how last time he had gotten all the way home only to find pickles had been installed despite assurances to the contrary. He explained why this mattered — how pickles should be banned from the human diet, and perhaps the canine diet. He mentioned how he wouldn’t feed a pickle to a starving man, as letting him die would be more humane. He repeated his instruction as a footnote in each phase of the ordering process.

“Will there be anything else?”

“No, that’s all. Just remember no pickles.”

“That’ll be $13.49, please drive around.”

“Thanks again for leaving those pickles off.”

In receipt of the greasy grub sack, he pulled away.

The family carriage thickened with the trademark aroma of the best assembly line feast achievable with salt-infused corn syrup. My brother and I salivated. It was a rare treat. The old man loved an occasional Big Mac, but harbored a visceral hatred of McDonald’s existence in every way.

He pulled over to the edge of parking lot. Rifling through the sack, he located his target. Gently opening the lid on the cutting edge cardboard crypt, he lifted the top bun, grunting in vague approval. I’ve seldom been more relieved. I was hungry enough to consider a clump of my own hair to hold me over.

But I was counting my gherkins before they were sliced.

What happened next was jarring and amazing. Whenever I reflect on it, there is a blend of mirth, shock, and fear which feels as real as it did decades ago.

The Big Mac’s upper deck was clean, but when the old man inspected the lower deck, it was crawling with pickles. Three, maybe even four. The hapless denizen responsible to build Big Macs in the meat dungeon had obviously gotten word of the pickle ban after building the lower half, and had been too lazy, ornery, or inept to undertake a fresh assembly.

“You motherfuckers,” he growled.

It was the first time I’d ever heard him use that word. My energy was focused on not laughing in a moment where doing so would lead to crying.

Then, all Hell broke loose.

He slammed the box shut angrily, crushing into inedibility the unsuspecting creation within. His hands gripped the steering wheel with the force of a cardboard bailer. He tossed the sack haphazardly into the passenger seat, senselessly jostling two sandwiches I can only assume were properly built, though they perished before we could know.

This was my intro to collateral damage.

I expected him to park, go inside, and hand someone their own lungs while kneeing them in the groin. But he was in a creative mood.

Dad pulled the car around to the drive thru, moving at undue speed as onlookers gawped. Motoring through an empty lane, he reached the open window where the sack had been handed over, reared back within the limited space available, and heaved a fastball so merciless Nolan Ryan would have smacked him on the ass in approval.

The projectile, a mostly inorganic jumble of quasi-food loosely packed into a rigid paper container, made injurious contact with a hapless employee. An audible thwap rang out, followed by cries of shock and pain. Dad growled a stream of profane contempt as he pulled away, so furious he was driving his prized carriage like a company rental, eventually slowing and easing as the minutes elapsed.

We sat in stone silence. No one ate anything. We went home and raided the cupboard for some peanuts and that most charming American contradiction, the cold hot dog.

It was a loose end never tied. He didn’t explain or smooth it over. His fully berserk irrationality didn’t fit his usual persona. He could have gotten a refund or a replacement. He could have taken the pickles off, or just eaten them. The man was constantly telling us not to get hung up on small stuff. If ever I complained about the food in front of me, he’d tell me I was lucky to have anything that didn’t make me heave or faint.

In the end, he paid $13.49 for food we didn’t eat, assaulted an employee who lacked culpability for a tiny mistake of no consequence, and broke the sound barrier with a weaponized meat slab. Then drove home in quiet self-defeat, never explaining actions so out of character.

Years later, I asked him about it.

He digressed into a story about Stan, a workmate who had gone nuts one day and beat the tar out of a coworker who’d made a rudely framed joke about Mrs. Stan’s private behavior. The guy had to be stretchered out of the factory, his kneecap shattered. So furious was Stan, the red mist aloft as the ambulance arrived, that he ran loose and resumed womping on his victim as he lay supine and defenseless on a gurney.

Turned out Stan’s wife had been having an affair, and he’d found out just that morning. He lacked the resiliency to cope with what would normally have been accepted as uncool but good-natured jawboning.

Dad’s message was simple. You never know what’s going on in someone’s life. Consider that. Assess demeanor. It was emotional intelligence before the term had a name.

He went on to explain that on the Day of the Pickle, he’d had a barrage of bad news. Everything had gone wrong all at once. He was getting laid off at work, having relationship problems at home, received a surprise tax bill in the mail, and found out his best friend had cancer. McDonald’s on Center Street had tested him at the wrong moment.

He felt bad about it. Not only had he set a terrible example, but who knows what life trauma the poor bastard he assaulted had going on. It was not his finest moment.

Over the years, my Dad would often digress into stories. It wasn’t a purposeful teaching strategy. He would just get distracted by his own thoughts and swerve into an example suited to the moment. He was a damn good storyteller, though I did not appreciate his skill at the time. Sometimes he’d be a good minute into a story before I realized we had departed the path and descended into the thicket.

Like most kids, I was too much of a dumbass to recognize the value in my Dad’s digressions at the time. It’s only via the slow dawning of my own age-earned wisdom that I’ve begun to truly appreciate his.

These days, I tell my own stories, and I know where I got the impulse and whatever ability comes with it.

Telling stories was a key element of my leadership style when I was in the arena professionally. But the moments were seldom planned. They were organic by-products of involvement and connection. My ghosts would tap me on the shoulder and remind me of experience relevant to the moment.

I would then share my meager insight before re-ascending to the topic or task at hand, often marking the transition with words my Dad never said because they were not his language.

“But I digress.”

II.

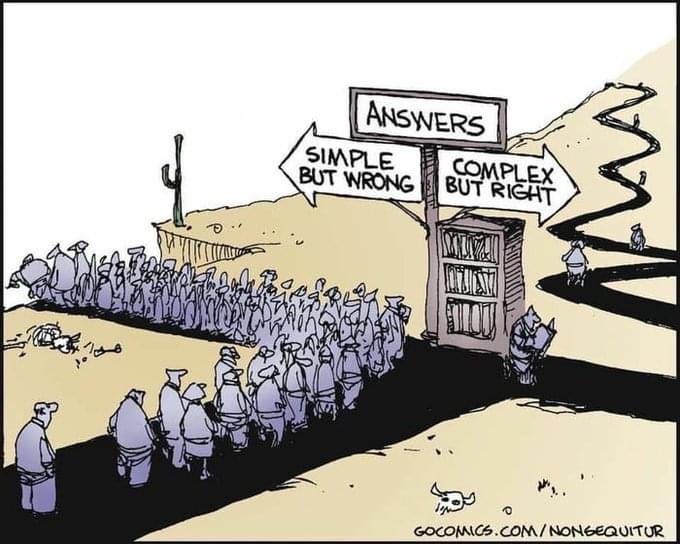

Our world overflows with information.

Every dam ever built to order and organize information has been shattered and swept away. But our brains haven’t magically adapted to handle the overflow. So we face a daily grapple to sort wheat from chaff. To dynamically decide what to skip, what gets skimmed, and what can permeate.

And what to fuss at.

What we’ve been realizing these past few years, and also not realizing, is how much information is spurious, overstated, understated, misstated, designed to mislead, or pulled from a random orifice and held out as legitimate.

Information is like sludge sucked from an underground oil field. Raw. Full of grit, sand, and detritus. Choked with impurities.

Only when we refine it does it become knowledge. Such refinement takes reasoning, skepticism, scrutiny, and synthesis. The tools of an active mind loosed by the humility of knowing how little we know.

Just as we can’t run our 10-cylinder SUVs on unrefined fossil gravy, we can’t run our brains on raw information. Not without sputtering, backfires, and breakdowns.

Information makes us ask questions. Knowledge helps us distill and triangulate answers. The answers help us make assumptions, arrive at sane conclusions, and make sensible decisions.

When we confuse the two, it’s like crossing the streams, which is very bad. Raw information leads us to make shitty decisions, and useful knowledge is constantly called into question rather than serving as a platform for action.

Which means we’re in a hell of a predicament at this moment in time.

A planetary predicament of overload, confusion, and mischief. A contest waged by those who understand how to organize and package information to influence, co-opt, or bypass the minds of the masses by collapsing distinctions between information and knowledge.

Information cleverly disguised as knowledge is everywhere. Knowledge is purposely mislabeled as information so it can become more debatable. What seems true often isn’t, and vice versa.

In such an environment, we license ourselves to believe whatever we want.

“Want” is a feeling. And thus, irrational. And thus, a poor platform for decisions. We often want things that are not good for us. Things that materially diminish us for the sake of being fat, dumb, and temporarily happy. Like a Big Mac while absorbing a Fast and Furious sequel and a bottle of whiskey.

When we are continually rewarded with dopamine and likes for indulging our feelings, we get ensnared in a neurochemical trap. Feelings become our primary navigational tool, and every time we feel good, we become more convinced our feelings are inherently right.

We become snowflakes, self-validating by pretending the world exists to conform to our preferences, attitudes, and appetites. That validation embeds ever more deeply when others agree, and we can always find those others online.

In a world where everyone is entitled to not just believe but live their own truth, consensus becomes elusive. We become not so much divided as atomized. Anytime we start to inch toward rationality by pooling facts or sharing questions, a fresh wave of message bombardment scatters us again.

Of course, we can’t live our own truths.

Many things we pretend to be true are mutually exclusive from truths asserted by others. Since we inhabit the same plane of reality, both can’t be true. So when we say we’re living our own truth, we’re really just saying we choose to believe something. Whether it’s true or not.

Which is another way of declaring oneself to be quite possibly full of shit. Not to mention stricken with the gross vernacular of Oprah TV.

In a land of bespoke and individually determined truth, collective action becomes vanishingly rare. Threats live rent free as inaction becomes a human contagion. The sludge once confined to underground wells bubbles out, oozing its filth into every crevasse. Eventually, it takes human form, zombifying institutions, organizations, and governments.

We wake up one day to notice important offices are occupied by invertebrate slobs we don’t consider qualified to serve as local dog catcher. Under the duress of distraction, we’ve voted sludgebots into high office, and we now whinge and wince at the inaction, distraction, and corruption they shake in front of us like a severed head.

In this moment, more information won’t help. It’ll gum up the works even more. More knowledge would help, but it lacks the octane to power us through the syrupy, slimy swamp we’re desperate to exfiltrate.

More capacity to refine information into knowledge would start to address our problem. But we’ve lost our longstanding and broad-based commitment to that idea. In fact, the sludgebot mafia are now hounding and heckling education, the most gilded of geese. Education is not only the key to a continuing an advantage in anything, but the key to human growth. There are a millions reasons why someone would want people to have less knowledge. None of them are good.

To rediscover enough shared clarity for collective traction, we need something else.

We need wisdom. That rarest salt of the Earth.

Knowledge that’s been lived and tested. Super high octane knowledge infused with the propulsive power of experience, failure, recovery, and reflection.

The good news is that there is plenty of wisdom to help us through this moment.

The bad news is that we’re looking for it in all the wrong places.

III.

Appreciation is often delay-fused. It occupies the conscience after a slow dawning of self-awareness. Long after it was earned.

I was a knucklehead kid. Typical underachiever with a decent brain and indecent work ethic. Feckless, fibbing fraudster with embezzled paper route proceeds in one pocket and a forged hall pass in the other. Smirking prankster and jovial attention hound laying truth to folksy witticisms about idle hands.

I nudged an elementary school teacher into retirement. He got censured for threatening to “choke the little bastard” after I told him he could “like or lump” my disruptions, which on that day had included removing every molecule of chalk from his classroom to delay his earnestly banal teachings.

I helped a football coach secure an unpaid stay-cation. He eased me onto the ground with a well executed lariat after I mentioned not giving “a squirt of piss” for his insights.

Such amusements were occasional pastimes.

But overall, I was benevolent. Chaotic good, we might say. At no point did I add to the population, subtract from the population, or find it necessary to establish dominance in a jail cell.

I left home at seventeen having done no one any real harm, including myself. Nor anyone any real good, including myself.

There were occasional flashes of what I might grow into. Spontaneous moments of field marshaling on a baseball diamond. Fractals of literary inclination, including a vaunted “A++” from Mr. Sample for a spellbinding narrative of love and loss starring Jack. He was my abuse-surviving hamster who, like many in his generation, died too young, never knowing the exquisite torture of teen angst.

My parents took no notice. Their indifference, punctuated by confused hostility, reinforced the isolation and self-loathing typical of every kid, ever. Which is why they are to blame for every bad deed I have ever committed.

I make sarcastic use here of the prevailing mentality of my generation. Persecution syndrome is the Gen X costume. Never mind that every generation of Americans is statistically dominated by well-fed, well-loved kids whose parents are often self-absorbed and aloof, but seldom ill-intentioned.

The narrative nevertheless demands that we all lay claim to being forlorn, love-struck, neglected misfits never understood by anyone, least of all the disguised aliens who raised us. All of humanity and high art depend on a steady supply of victims.

But on reflection, it’s become clear to me I was never a victim. Never neglected. Never a misfit. At least not in the ways channeled by punk rock or John Hughes.

I was given more than I knew by a man who never explained and probably never realized what he was giving me. I shall explain.

IV.

Not even a half-clothed supermodel with a 100-volt cattle prod could tempt or coerce my eyeballs onto the pages of a textbook. But I was weirdly devoted to consuming every word of the newspaper, every day.

This smacks of garden variety youthful contradiction. But it was actually an early yearning for knowledge of the great beyond. It led to a skull full of trailheads for the pursuit of greater insight. But also a head ringing with dissonance.

In the mid-80s, it became obvious my home town was dying. Vacant buildings, peeling paint, cracks in the sidewalk with weeds growing through them. Beat up cars kept rolling via second-chance rust vessels unearthed from local junkyards more numerous than grocery stores.

Our baseball uniforms, sponsored by local businesses, went from decent cotton to polyester so cheap it would disintegrate in hot water. Cold washes left every kid wearing stains all season long. By September, we all looked like dumpster-raiding railway hobos.

Some of us looked like hobos anyway, like the kid in the red sleeves below. This is what getting traded after the season starts looks like. Such late moves mark a player as either a hot prospect or a spare part. Little doubt in my mind which applied.

You can sometimes read an American town’s fortune by outlining the story of a single strip mall. Foot Locker and The Gap closed their doors, replaced by Payless and a thrift shop. The video arcade became a gun shop. A large dirt mound later, it was equipped with its own firing range. You could shop for discount pleather sneakers to the sweet symphony of spent rounds.

Once a bucolic and tranquil enclave teeming with with nuclear families happily drenched in the ennui of stability, it was rusting like a saltwater shipwreck.

There was steady growth for movie rental shops and video game retailers, as escaping reality became more sensible than confronting it.

Fast food establishments multiplied like spring rabbits, as people working longer hours for less money sought the convenience and affordability of expertly disguised, edible salt formations disguised as tasty treats. As repeat dopamine flooding entrenched cravings, demand escalated further.

But while slinging burgers gave many a factory laborer and industrial tradesman the means to survive as the economy’s manufacturing foundations crumbled, it mainly became true that people willing to work couldn’t find decent jobs.

When that goes on long enough, they become unwilling to work. But they still need money, especially once they turn to booze, weed, or some other Novocaine.

If you won’t work but you need money, you get it by other means. Such as selling drugs, stealing, running scams, defrauding systems designed to rescue the legitimately needy, or borrowing from any bank or person fool enough to lend or violent enough to collect by other means. Or by frequenting pawn shops which soon outnumbered the junkyards, each with ample dimly-lit parking for the shady machinations of life in the underbelly.

Everywhere I looked, the past looked a lot better than the future.

And yet, according to my daily newspaper, America was booming. The mayor, governor, and president said it was morning again. Prosperity was spreading like a virus of joy. Giddy denizens were buying property, raising Budweiser toasts to low inflation, and cosplaying scenes from Leave it to Beaver.

Reagan told us to embrace optimism. Endorse low corporate taxes. Endorse free trade. Support a reduction in government services, which will shrink government and lower tax burdens. Consent to privatization. The dispensed wisdom indicated that supporting an ascendant vision of unregulated capitalism wasn’t just the key to a Utopian future, but it was the hidden hand behind an unfolding Utopian present.

Children are too naive to be cynical. Their minds are open and curious.

So I asked my Dad why there was such a huge divergence between what Reagan described and what we could see with our own eyes. In retrospect, he showed remarkable poise in delivering a calm answer.

“Well, some of the difference is because of where we live,” he advised, going on to explain to me how Ohio’s industries were especially exposed to the particular changes of that time. But then he made his real point.

“Never get your wisdom from a salesman.”

He explained how Reagan was selling a vision designed to earn the consent of the voting public. If he could make everyone believe their lives and futures were rapidly improving because markets were more free to create broad-based prosperity, he could secure permission for more deregulation, more union-busting, and more corporate solutions to public problems.

These things would shape America in the way many wanted.

People bought what Reagan was selling. His 525 electoral votes in the 1984 election still stand as the most ever cast for a presidential candidate.

Ohioans did not benefit from this decision, which ran contrary to their interests. 66% of the votes in my home county of Marion were cast for Reagan. They trusted in Ronnie’s wisdom, and the corrosion of their way of life hastened.

As countless millions became slow-motion victims of their own votes in the years that followed, I managed to remain largely unscathed. Because I started getting my wisdom from people who were not trying to sell me anything.

People in the trenches.

Ordinary people.

V.

Absorbing the wisdom of ordinary people made it clear to me my life would be better if I got the hell out of my hometown at the first opportunity.

My Dad, despite his grimly accurate assessments of industrial enshittification, had given me little explicit preparation for navigating the adult world. He figured I’d figure it out. And I did figure it out, but not in the way he figured I would.

Over his objections, which fostered years of mutual strain and silence, I enlisted in the US Air Force immediately after high school. The decision wasn’t an informed or deliberate one. It was part impulse and part intuition.

But it was also pragmatic. Self-aware.

Because I knew two things. First, that I needed to get out rapidly or I would stay forever. Second, that I was not ready for the double-edged freedom of a college campus.

I needed to mature. I needed to learn a trade. I needed regimentation and guidance. For the first time, I didn’t choose the path of least resistance. Going the hard way felt right.

And it was right, at least for me.

From day one, I knew it had been the right call. It was like catching lighting in a bottle and riding the thunder for decades. Instantly, I found that a life of discipline, values, and team achievement under pressure innately resonated with who I was.

I had a fantastic career, never looking back.

Except I did. Often unconsciously, glancing aft to refine where I was going by making reference to where I had been.

Traversing the phases and segments of life, raising my own family and developing my own ideas about the world, gave me increasingly compelling reasons to let the backward glance become a reflective gaze.

After the last engine shutdown checklist was complete and the rippling commotion of a second career came and went, life got quieter. Calmer. The nest emptied. Roots went deeper into the soil of our family’s chosen settlement.

No longer responsible for thousands of people, I discovered one of the great joys of life, masked from my reality across three decades of professional demand and operational intensity punctuated by parenting, travel, love, and red wine.

That great joy: idle time.

Time to think. Or stare at the wall. Or exercise. Time to write stories like this one, free of the creativity-crushing vice of a merciless deadline or the cranial burglary of a desk-pounding boss suckling at the teat of corporate approval.

For 35 years, I’d occasionally borrowed some of my life on consignment.

Suddenly, I owned it.

After the Air Force, a new project loop had opened. It was the project of figuring out who I was when I wasn’t wearing a uniform with a shoulder-mounted insignia. Of gradually bringing that innate sense of self to a conscious place. Of deciding how to interpret the wonder and decrepitude of the world when no one was telling me what to think.

A decade later, idle time had provided the final resource necessary to close that loop. Like a last, reluctant drip of molasses, self awareness seeped out of nerveless marrow into my bones, where it could stimulate and be felt.

The delay fuse finally detonated.

I felt appreciation. Not merely for the material impact of my Dad’s iron-plated work ethic and selfless commitment to family. But for two other things.

First, his advice on getting wisdom from ordinary people.

Second, his wisdom as an ordinary everyman who lived the timeless reality of working class American life.

It never occurred to me his stories were anything other than mental and verbal detours from the task or moment at hand.

Until it did. Maybe because I finally had time to let it all sink in. Maybe because my mind, after spending decades tensed into rigidity by pace and challenge, finally became limber enough for a broader stream of consciousness to seep in.

Maybe because I would soon be a grandfather, and felt the gentle dig of nature’s spurs urging me toward a campaign of wise counsel for the mind of a new prince.

Something clicked, and the old man’s words lifted from the mental pages of his stories and took their shape as platinum-encrusted maxims capable of lighting the paths of life.

Without ever explicitly commanding me to listen or heed, he managed to bake into me the timeless, durable, sublime wisdom of an ordinary man who lived a life marked by constant acts of ordinary heroism, quietly providing two of the hands keeping the world aloft.

VI.

Atlas, it turns out, wasn’t one man.

He’s a heuristic representing the combined toil of countless millions. With calloused hands, they lift and carry civilization. While princely politicos freshen their mascara for donation dinners and executives pass collection plates during inveterate sermons of commercial faith, ordinary people spin the globe fast enough to give it gravity. They keep the roof from leaking so the house party can roll on.

My Dad would have been 77 a couple of months ago. I choose this moment to share his wisdom with you. I don’t do it for him, for reasons you’ll understand in a few paragraphs.

I do it for myself, I suppose. For the pure act of expression, and for the sense it helps me make of life in a world gone mad.

I don’t necessarily share this wisdom for your benefit, but I hope that’s an ancillary perk, and that maybe you’ll even share some back. But experience tells me that if I want anything which follows to be of any value, I’ll have to first persuade you to lower the thick mental shields typically equipped by all of us as we wander in a world so crowded with towering bullshit that we seldom catch a ray of truth.

So here’s my plea.

Don’t buy into the spicy online witticisms of those my age, including my own. Underneath it all, we’re huddling in the corner of a self-made psychic prison of perpetual nostalgic agony, bewildered that our parents dared to live lives, carry scars, develop problems, or be human.

Maybe that’s true for all generations. Maybe none of us ever stop re-living the various traumas that wounded us as we took shape, and shaped us by their wounding, be it real, embellished, or totally imagined.

But I’ve noticed in my generation a particular craving for simple explanations and a particular allergy to complex realities.

This gives us an excuse to do what punk rock, John Hughes, rat psychology, and high school mythology encourage. Which is to attribute our inadequacies to those fiendishly neglectful 1980s parents.

You know, the ones busy making sense of simultaneous and orthogonal tectonic shifts in the social norms, financial contours, and employment realities of an increasingly schizoid American narrative, bouncing constantly between “it’s morning again” and “we’re all gonna be nuked.”

We shouldn’t be stunned that our parents, crawling out from under the shadow of Vietnam to find a landscape dotted with bomb shelters, junk bonds, and rusting factories, turned to hedonism and hair metal as coping mechanisms.

And of course, we’re not stunned. We’re just rationalizing. Every generation’s loudest voices blame parents and kids for the world’s ills, conveniently overflying themselves.

My take is different.

When I think about the personal challenges I’ve faced in life, I’m grateful for their relative scarcity and convinced they became my total responsibility the day I slung my hook and left home for good.

It’s not that I disown Gen X mythology. It’s fun. I was as sure as the next mousse-haired punk that my parents were Martians wearing human skin, embedded to conduct espionage and emotional torture. They didn’t understand my struggles. They couldn’t live my truth. They were committed to my unhappiness.

But when I look back, I see the quiet turmoil and isolation of growing up in a broken home with material scarcity and awkward relationships as one of my life’s greatest blessings.

Had things been different, I’d be different. Had I been closer to family, it might have had less to prove, reducing the energy I drew upon to achieve and build. To prove to the world, but more importantly to myself, that I had the guile and substance to be something.

The void of meaning I felt scaling the city wall to make my escape gave me something to chase. A reason to be open to the world. I found meaning in service, in education, in the contrast and self-discovery that accompany travel and adventure. Most critically, I found meaning in a relationship that didn’t just improve the picture of my life, but became a new canvas. In that, I became my own person with my own soul, the tethers of home severed, lashed elsewhere.

Being grateful changes the lens. It helps me glimpse the good things when I look back on trying times. Those good things orbit the memory of my old man.

He’s been gone a while now, but as the years tick by, I find the wisdom he imparted ever more insightful.

I hope you will too.

VII.

Extraordinary people are the flames moths struggle to resist. They speak with authority, or seem to. They speak with credibility, backed by wealth and power and institutions. They have brands, logos, and expensive suits.

And they’re mainly full of shit, even if they don’t know it. What they dispense as wisdom is actually manipulation. They want you to buy something. They want you to believe something, and live their truth. They want you to vote for something.

The smarter they sound, the more likely they are to keep you buzzing around their flame.

But their wisdom changes with the shifting of the tides. What sells today will be a bygone fad next week. What supports political interests, commercial motives, or ideological factions will change as frequently and sharply as mountain weather.

Remember Mr. Popeil? Betamax? The Ford Pinto? All revolutionary. All very much commercially dead as quick as they were birthed.

Remember when lying, cheating, adultery, and immodesty were uncool? Try getting a job as an executive or media personality these days without documenting at least three of these as habits. To get elected, you’ll need all four plus either jail time or documented mishandling of state secrets. Unless you’ve been caught naked with a bowl of jello, which is like an electoral FastPass.

Remember when Russia was our sworn enemy because they oppose human liberty? Pepperidge Farm remembers. It also remembers when “Pepperidge Farm Remembers” was a commercial jingle implying the wisdom of unbridled nostalgia.

Temporary things are a false basis for wisdom, because the wisdom they claim to generate is as temporary as the context in which they exist. As they vanish, what was claimed wise is exposed as something less.

Ordinary people live a timeless reality. The are born, they work, they love, and they die, trying to do it all with dignity. They harbor no grandiose visions of changing the world. They struggle through it as they find it.

So when they offer wisdom, it has greater purity. They aren’t selling. Their voices express knowledge refined by experience, suffering, failure, recovery, and a level of stubborn perseverance only distilled in those who have negotiated to survive and done so under threat.

Extraordinary people sail yachts. Ordinary people mold their hulls and stitch their sails. You can choose to take advice from either, both, or neither. But as you weigh the question, ask yourself which one is more in touch with common reality. Which will be relatable. Which will empathize enough to help you.

Which might be walking around in quiet possession of true insight.

Below are a few thoughts from a wise man. Nearly always delivered spontaneously, when something jarred a thoughtful digression. A story illustrating something he thought I needed to know.

It took a while for these pennies to drop. But they turned out to be minted from solid platinum.

Hope you enjoy Dale’s Digressions.

“Nobody cares.”

If you’re waiting for the world to congratulate you, bring a sack lunch. It’ll be a long wait.

No one’s going to care about you. Most people won’t even notice you. They’ll never see or appreciate your work. Accolades, promotions, and degrees won’t mean anything beyond your own skull.

Social media makes everyone feel more seen and important than they actually are. They become celebrities in their own minds, walking around to their own theme music. But the reality is we’re all just walking barcodes getting scanned as we move through stages of workaday obscurity.

The more you expect to be validated, the harder you’ll fall when you realize the world is an inherently selfish place. Whatever anyone says, they’re mainly trying to look after themselves, and that’s okay.

If you’re lucky, you’ll have good people in your life. Family, close friends, maybe a battle buddy. They’ll genuinely care. They’ll feel your wins and losses with you. They’ll pick you up and knock you down when you need it. No one else will, no matter how much they want to. No matter how much they pretend to.

The sooner you get that, the sooner you’ll start achieving things for yourself, and for the benefit and respect of your close circle. This helps you avoid wasting energy. It helps you prioritize.

And it prevents the hollowness people feel after pissing away part of their life trying to impress people who don’t care about them.

“Any territory you surrender will have to be re-taken at double cost.”

Once upon a time, the neighbor’s constantly unhinged dog decided to hold a solo digging festival in our back yard. It left a decent lawn looking like a groundhog preserve. Incensed, my father ran it off with huge stick in his hand, teaching local kids a few new expletives in the process.

Smiling, the dog leapt the chain link into its own yard before doing an about face to taunt the old man as he made his way up the walk to roust the hapless resident who soon answered his angry knocks.

He told the guy to control his dog. The guy chuckled dismissively. He said if happened again, the dog would come home with a limp, or not at all. This prompted the man’s daughter to instantly melt into a panicked sob, while the neighbor himself nervously chugged on his cigarette. His body language turned deferential, his presence shrinking along with his grin.

“Won’t happen again,” he said.

And it didn’t.

Afterward, Dad crystallized this moment with a story from Vietnam. Having taken a hill at steep cost, his platoon were ordered to march on, leaving unguarded what they had just shed lives and limbs to possess. The enemy soon reoccupied.

Not only that, the enemy was emboldened. They realized Americans were not willing to commit enough resources to hold what they captured. A demoralizing, bloody game of whack-a-mole ensued for Dad’s unit and countless others. Worst of all, they were routinely ordered to recapture territory they’d already taken, always at a steeper cost against an enemy on notice of their intentions.

It was the same in civil life, he advised. The instant you own something, how you protect it sends messages.

If you won’t protect your yard, the dog will consider that he owns it and can shit in it whenever he wants. The dog’s owner will clock that too, and tell every banjo strummer he knows. The next move will be on your garage. Then your truck. Then your house. Then maybe your family. Soon, you’ll have to fight to reclaim what’s yours. That fight at least doubles your cost, all because you messaged an invitation vs a deterrent.

On the other hand, if you make yourself an uncooperative target, if you push back and stand up, if you find that bit of menace within yourself when you need it, lunatics will find some other sucker to heckle.

People commonly think about this idea in the security domain, but it’s a general rule of human interaction. I think about how willingly American workers gave away their unions. They’ll have to fight twice as hard to get them back, but it’s the only alternative to the modern feudal system actively sought by corporations.

“Doing the right thing is never wrong. Doing the wrong thing is never right.”

Dad spent some years as a foreman on a production line in a factory which packaged cereals. The work was grueling and repetitive. Each worker needed basic machinist skills to remediate minor faults and keep the line running.

In the early 80s, looking to pay a lower wage and save on labor, the plant stopped requiring a machinist qualification. Efficiency dropped, which triggered managers to put pressure on frontline employees to keep the line moving. This in turn led to an increase in safety incidents as unskilled linesmen attempted to work around machine issues rather than pause and fix them.

On my Dad’s line, this culminated in a near miss. One of his men was responsible for positioning boxes and moving them under a pneumatic box press. A super-heated plate contacted the box for a couple seconds under the right pressure, the heat activated the adhesive on the flap, and the box sealed. A minor fault caused the press to cycle at an irregular interval. The unskilled linesman didn’t know how to fix it and had been castigated for clogging up the line earlier in the week. So he did his best to guess the irregular press interval.

He guessed wrong. Fumbling to position the box, he got his hand in the way of the press and couldn’t quite retract it in time. His thumb sustained a third degree burn, with only the presence of a blackened and dead thumbnail preventing a much more serious injury. Hearing him scream out in agony, Dad smashed the emergency stop, sent his entire line on break, and joined them himself after rendering first aid and sending the worker to the hospital.

His manager found Dad in the break room talking to his guys, his characteristic unfiltered Marlboro drooping from the corner of his mouth as he coached them on distinguishing workable from unworkable machine issues.

The manager told him to get everyone back on the line.

He told the manager to pound sand.

He wanted the press fixed first, and he wanted a qualified machinist for the problem station. It turned into a pissing contest, and my old man carried a lifetime undefeated record in those. He was suspended for three days without pay, and gave zero fucks about that. He happily caught up on some home projects.

Then he went back to work to find the situation was no better. So he stopped the line again, repeated the cycle complete with the pissing contest, and got suspended again. When he returned, he was pulled into a meeting with his boss and HR. They showed him a risk assessment, quoted him an OSHA standard, and explained that repairing the press was scheduled for the next down day.

“That’s all fine. Just give me a machinist for that station and I’ve got no issues.”

The manager refused. The company didn’t want to set a precedent that machinist skills were required, which would go against its move to hire more unskilled workers at a lower wage. A third stalemate developed. His job was threatened. He was reminded he lacked the authority for managerial decisions, and that stopping the line without a valid reason was against policy.

“I won’t put someone at risk after there’s already been an injury. It’s wrong. Nothing you’re telling me makes it right. Keeping the line still and fixing that press is the right decision. Nothing you’re telling me can make it wrong.”

That night, the line was paused for four hours on the midnight shift so the press could be troubleshot and repaired. Dad went in and helped fix it himself.

In my own professional journey, I’ve applied this principle many times. I’ve also paraphrased it as “keep the easy things easy.” Moral clarity is rare, so when you have moral clarity, don’t waste energy trying to make things murky. Just do the right thing.

Today’s work cultures are shaped by corporate financial obsession that’s been permitted to metastasize and spread to the front lines of organizations. Financial obsession rides the horse of bureaucracy, and bureaucracy will do whatever it must do to protect its interests. It’ll make up policies, limit speech, starve workers of information, bully and coerce compliance, and ultimately attempt to criminalize doing the right thing if it hurts the bottom line.

But not even the black magic of bureaucratic wizardry can make it wrong to do the right thing, or vice versa. My Dad could have lost his job, sure. But in his mind, a job with a company that would fire him for insisting on basic safety wasn’t worth having anyway.

As an interesting footnote, my Dad caught the employee who burned his thumb — the one he almost got fired trying to protect — stealing an expensive impact wrench from the plant. The guy rationalized his actions by falling back on the company’s previous disregard for his safety. Dad reported him anyway, and he was fired.

Because doing the wrong thing is never right.

“Life Is Obligation.”

The old man liked to strum his acoustic guitar, gently humming to Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot, or Bob Seger. I found out later that it was a replacement for a previous guitar he’d pawned off years earlier after getting laid off for a few months. He ran out of cash reserves, yet the mortgage came due. So he did the responsible thing.

“Life is obligation,” he would say when anyone complained about the weight of responsibility.

“Life is obligation. And that’s okay. It means you matter to someone. When people depend on you, they are trusting you to deliver. That makes you important. It gives your life meaning. I can’t imagine anyone being happy if no one needed them for anything.”

Our world revolves around this idea to a much greater degree than we realize. If ordinary people summarily paused their sense of duty, every expectation we have in everyday life would destabilize. The whole world would wobble. But the assumption is safe, because responsibility is safe in the hands of ordinary people. It’s how their lives are defined.

I’ve found a lot of resonance in his advice, but I’ve also found it incomplete, and even dangerous in the wrong hands. Getting addicted to obligation is costly to one’s own agency and time. You can wake up one day to find you’re so busy doing things to support everyone else that you’ve obliterated yourself. You’re no longer doing the things you enjoy, your mental and physical health are not good, and when you stop and actually assess your happiness level, the needle on the fun meter doesn’t lift (or it’s pegged, depending on your commitment to sarcasm).

He went back for his guitar a few months later and it was gone. One of many examples of quiet sacrifice of his own joy to be responsible for his family. But it gave his life definition, and I’ve found the same to be true in my own life.

“Don’t Waste Time on Liars.”

A few old buddies would come over and knock back a few beers with Dad occasionally. Guys he’d been with since high school, and in one case all the way through his tour in Vietnam as well.

I noticed one of them stopped showing up for these occasional hangouts, and asked where he’d gone.

“He lied to me. We’re not friends anymore.”

He could get along with anyone, my Dad. He was inclusive before it had a name. Smart, dumb, old, young, native born or immigrant, similar or different. He didn’t care about any of that. But he had very few people in his friend circle, because he only kept people there he could trust. If they proved otherwise, they were gone.

The guy he stopped hanging with had partnered with him to restore an old GTO, and they agreed to split the proceeds when they sold it. But the friend sold it for a few hundred more than he represented, shorting my Dad a chunk of his half. He found out about it, and that was that. The guy offered to give him the money. He told him to keep the money but never call or visit again.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, you can fix stupid. With education and mentorship, a fool can become less foolish, perhaps even smart.

But experience tells me you can’t fix a liar. Avoiding truth is a reflection of moral cowardice. It speaks to character, and that’s near impossible to change with anything less than mortal shock.

When I started my career in the Air Force, integrity was a core value and a prominent feature of service. Honor was required, and therefore reliably assumed in teammates. If they came up short, they were off the team.

By the time I retired, dishonesty was the norm. Executive shitlords had driven the service into a bureaucratic ditch, leaving values at the altar of budget while inventing new ways to mismanage and then lie about it.

It happened because early stage moral lapses were rationalized and tolerated under the mistaken notion of protecting interests. But if you have to tolerate lies to protect something, it’s not worth protecting. In fact, you’re surrendering to whatever it is while persuading yourself otherwise.

When you get fleas, don’t blame the dog. He’s doing what he does. Blame yourself for thinking you were doing him a favor by protecting him from flea treatment.

“Trust an Employer Like You Trust a Crocodile.”

Work is a contract, not a friendship. People get fooled into trusting a company because they become friends with their boss or buy into company values. But at the end of the day, your employer will do what serves company interests. If that means leaving you jobless, homeless, or hopeless, they won’t lose a wink of sleep.

My Dad had a guy on his factory line called Herman, a modest and middle-aged Marionite who’d served fifteen years on Navy ships, mooring ashore five years short of retirement to rescue his marriage.

Unfortunately, his wife developed a serious mental illness and needed additional support.

Herman repeatedly asked for a shift change. Denied by manager. Asked for time off. Denied again. Asked for a few hours away to attend an appointment. Denied again. He escalated, following the process steps to appeal his manager’s decisions. Every time, denied.

Painted into a corner, he eventually lashed out, sharing a few excerpts from a seething inner monologue with the entire shop floor as he stormed out in a rage. His rant included industrial language capturing his opinion of the general manager, the general manager’s wife, her mother, and various others.

He was fired for cause. This left him with more time but limited material resources to support his wife’s treatment. She eventually took her own life. Herman did the same not long later. A tragic spin-off of a common work tale, and a grim script that continues to play out constantly to this very day.

Employers are driven by ice-veined rationality. They will liquidate and delete anything that gets in the way of those interests, to include employees they tricked into feeling something extra-contractual.

Look no further than the legion of ambushed workers recently cashiered from big tech companies despite record profits, cash flows, and tax breaks robber barons admire from their flaming recliners in the pit of Hell. The smiling snakes running today’s soulless profit foundries are in the stride of creating a saw-toothed reptilocracy devoid of basic protections or fairness. Dehumanization of human workers is an assumption of their plan.

But it’s really just a re-framing of an old picture that hasn’t changed much over time.

A manager who is your friend one day will scapegoat you the next to save his job. A sergeant will send you on patrol to keep himself inside the perimeter.

When you start confusing work with a familial relationship, you’ll start to care. When you care, you’ll be vulnerable. Then, you’ll get burned. Too many times getting burned, you’ll get fragile, and the world doesn’t treat fragility with kindness. It treats fragility with cruelty.

Being the misguided knave I was and arguably still am, I translated my Dad’s cautionary wisdom into a Quixotic call to action. I set out to change the world. You know, as one does.

I sought to prove workplace relationships could be real. Trust could be built even within contractual boundaries. A general manager or commanding officer could genuinely care, and not only would the trust extended by employees be validated, but they’d work harder, give more, and hit higher notes as a result. There is no law of the universe that people must be miserable in their work, I told myself and sermonized to others.

This worked in the military to an extent, though it became obvious to employees that the biggest decisions impacting their lives were centralized and made at galactic levels in distant locales. So even if they trusted me and each other, they knew my authority was bounded within tactical execution. Pragmatism demanded they limit investment and stay emotionally detached.

In the commercial world, I’ve learned relationships are not merely misguided, but a dangerous idea. I built tightly-knit teams with high levels of belonging and mutual support. Time and again, those teams were blown apart by corporate cost spasms. I was left holding the bag, acting as the face of a company ravaging teams for a margin so atomic I couldn’t begin to honestly rationalize the impact to people and families. It was the drip that broke the dam of my time with Amazon, and I’ve since watched the company totally abandon any semblance of employee loyalty.

There’s another useful footnote lurking in this maxim, and I’ve seen it play out many times now.

Like everything going back to when hills were pebbles, employers have fat years and lean years. In the fat years, everyone can win. Businesses struggle to match talent to growth. Jobs are safer, opportunities abound, and collaborative attitudes can prevail. As the party rages on, clown-shoed executives piss away money like tomorrow’s never coming.

But for the wretched living, tomorrow always comes. When the lean years hit, someone has to lose. Companies trim or lop their labor forces. They study each segment of the talent pool to isolate and hunt the slowest gazelles. Employees know this, and become pragmatic about keeping their jobs, which fuels a zero-sum culture of cutthroat competition.

This instantly vaporizes any residual shreds of relationship culture. Which explains why companies always seem to be reinventing rather than reviving their cultures when fat years return and retention again matters.

“Funerals Are Not For Dead People.”

Whatever trace of spirituality my Dad took with him to war was scrubbed away by what he saw there. Some soldiers become more devout to cope with what they experience. Others become convinced no God would preside over such senseless savagery. Dad was the latter.

When his lifelong pal and fellow veteran died, I asked why he skipped the funeral and didn’t go pay respects.

“Pay respects to who?” he asked rhetorically. “He won’t know I am there. He’s dead. The funeral is for the living. So we can try to make sense of his death and commemorate his life. I don’t care to do those things with those people.”

He sat quietly on the back porch with a six pack that night, watching the sun go down. He didn’t need the loss to make sense, but he did commemorate in his own way.

Many things we do for ourselves despite saying and even believing they’re for others. Companies, governments, and agencies do this too, sometimes being deliberately performative while other times over-estimating the value others will place on things.

Every peak season, Amazon showers warehouse associates with penny chocolates and holds impromptu prize draws. Who asks for this and who is it really for? Is this about creating an appearance without real investment? Is it just a weird form of tithing so managers don’t feel guilt about working conditions?

Take a look at how many employees are sent packing in January for a clue to the answer.

“Shake Hands With Strangers. Keep the Other Hand Free.”

I was too young to remember it, but the story was shared with me later about the time our family van broke down during a trip to Washington, D.C. The neighborhood was rough. This was long before mobile phones.

My old man stood over an open hood troubleshooting while his young wife sat pensively in the van, an infant and toddler obliviously fussing in their seats. Many eyes peered while others leered at the out-of-towners broken down on a side street in a strange place, their safety in the balance. He knew it was a vulnerable moment. He could feel the risk. He was angry at himself for needing help. But to get out of this, he would have to trust a stranger.

After a few minutes, a passerby pulled over, popped his trunk, and approached. Dad smiled and shook his hand. They talked, they stood over the engine and mumbled in unison. The man grabbed his tools and some duct tape. A temp repair got the engine gargling back to reluctant life and we limped our way to a nearby auto parts store, the helpful stranger shepherding us from a few car lengths behind before waving a smiling farewell.

“I got lucky. The right stranger found us first. It could have been different. When you shake hands with a stranger, keep the other hand free.”

Years later, Gen. James Mattis described the razor-thin line dividing peace and menace in fragile negotiations with Taliban insurgents. “Be polite, be professional, and have a plan to kill everyone in the room.”

There can be no progress without risk. But it is a potentially lethal error to accept risk without thinking through the what-ifs.

I heard in Mattis’ maxim the echoes of an old lamentation my Dad shared.

“Be kind to strangers. No one is kind anymore. The world is scared of itself. Strangers and even neighbors are scared by default. No one wants to risk confrontation because everyone’s got a gun these days. When neighbors don’t talk to each other over minor stuff, things fester and they get alienated. They don’t communicate, so they assume the worst in each other. Sometimes, they’re correct. Usually not.”

He was talking about how fear, mainly unwarranted, had atomized once close-knit communities. Security cameras, guard dogs, cans of mace in purses, revolvers in glove boxes. Half the world was selling how scared we should be while the other half was buying it, literally.

“This is why we don’t have shared gardens in town anymore. Everyone has locks on their doors and privacy fences. Cars are parked everywhere because no one carpools anymore.

“But at the same time, a little paranoia goes a long way. Bad people prey on the kindness of good people. So be kind, but don’t be naive.”

Being kind to others takes more courage than it should. But unless we muster that courage, we continue toward a future where there is no “us” anymore. Just a gaggle of humans situated in a common locale, but no community.

The evidence says we should be less fearful of crime now than ever before. The threat is always there, so keeping a hand free during a handshake is always sensible.

But we must keep extending hands.

VIII.

My father shared a lot of wisdom with me, usually with such unintended guile that my mind was totally open, no guards raised.

And yet, it took many years for a lot of what he shared to really hit home.

His gift, and the source of much of his wisdom, was being a fish in a school of fish.

But in his digressions, he showed himself to be more. A big fish. An intellect and conscience unappreciated in his time. The guy you walk past in the store, perhaps trading a friendly hello or a soft glance, never knowing how special and powerful a person you just bumped into.

Many of the axioms and common notions we permit to shape our perspectives and guide our decisions are highly suspect.

In some cases, wisdom is no longer wise because it hasn’t been meaningfully revised since it walked off a 17th century farming plot. In some cases, it was never wise in the first place.

But most of the time, it was never wisdom. It was something else, painted with the clever livery of wisdom but serving as a vessel for persuasion, grift, or manipulation.

Wisdom doesn’t have instrumentality. It is just truth about the world, fit for common consumption. It is the oatmeal of common parlance.

Ordinary people know the world in ways special people don’t. And most of us, at the end of the day, are ordinary. Communications architectures of the current day want to convince us otherwise, but we will only suffer by giving in to that delusion.

My Dad was an ordinary fellow. He told me stories. They contained timeless wisdom.

It took me a long time to recognize what I’d been given. But just as every day is a new opportunity to be an oblivious moron, it’s also an opportunity to drink old wine and reach new consciousness.

I realize now the priceless value of wisdom ferried via innocuous digressions.

Sure, no one will care in a hundred years. Sure, we’re all just ants on an anthill, making enough money to play along and build a life where we can cultivate the relationships that serve as life’s only dependable source of joy or fulfillment. Sure, neither a pink slip nor a bullet knows the difference between a wise person and a damn fool.

But none of that makes it more or less possible to live your own truth. None of it makes banana peels less slippery, or cats less interested in playing fetch.

And none of it makes wisdom less wise.

But I digress.

Tony is an American writer.

Outstanding. Thank you for sharing the wisdom.

TL;DR at its best. Loved it all the way to the end.