One of the skills I collected as a commanding officer was reading the sound of approaching footsteps. Hard heels and long strides are confident. Soft, short steps sound like the anxiety that often accompanies bad news.

Arriving via a trail of tentative shuffling, Captain Jelleau tapped on my open door, eager to burden me with a new problem.

I considered it then, and continue to believe steadfastly, that grinning through mental fatigue and listening to sometimes tedious problems is a big part of any leader’s job. When your people stop bringing you their problems, you have no reason to exist.

To understand Jelleau’s predicament, we must grip onto a clutch of Air Force vernacular.

A “booster club” is a front for the collection of unofficial revenue for unofficial purposes. Prominent among these, to buy gifts for teammates when they depart for pastures new.

Booster clubs make their money by selling beer and snacks in the squadron “heritage room.”

A heritage room is a bar. It can’t be labelled a bar because someone decided that would be too much like the Air Force encouraging boozing. Which, of course, it does and always has. But mustn’t do openly.

In our squadron, the standard going-away gift was an American flag flown in combat, and thus imbued with the solemnity and fighting spirit of our shared calling. Folded by the Honor Guard, it would be presented in a triangular case with a personalized, etched placard. Something like this.

As president of the booster club, Jelleau was responsible to procure the flags. Any gaps impacting gift presentation could get him impeached.

He’d recently bought 25, spending a few hundred of booster club funds. He’d brought one to show me, in his words, how he’d “screwed the pooch.”

Carefully unfurling it, he showcased its high-quality stitching, sturdy fabric, and obviously superior color-fastness. It was satin smooth, a sheen of distinction radiating from those hallowed stripes and precious stars which had pulled tears from my eyes more than once. It was a thing of beauty.

I didn’t see the problem. My growing impatience was communicated non-verbally, as Jelleau’s twitch grew toward a tremor.

He grasped fabric where the stripes met the binding, isolating the manufacturer’s tag. He held the tag flat so I could make out the imprint.

And that’s when I understood the problem.

“MADE IN CHINA”

It wasn’t a crisis. No taxpayer dollars had been harmed, no patriotic commandments violated.

But it felt oily and wrong to contemplate giving a Chinese-made US flag as a gift in a military unit. It was definitely “distant cousin” territory. You might date your distant cousin and never know it. But if you found out they were your distant cousin, you would stop dating them.

Worst case, we were out a couple hundred bucks. Yet, I felt the itch of a dilemma. My interest was in giving our people a beautiful flag. It would be unacceptable to give them anything less.

I asked Jelleau to order a couple of samples using approved vendors from the government purchasing catalog. When they arrived, we examined them together. The fabric was like a sheet from a cot in a refugee camp. The stitching felt like singed horse hairs twisted around chicken wire. Even the eyelets were cheaply made and somehow already tarnished, like they’d been cannibalized from a pair of old work boots.

And for the privilege of this shoddiness, per unit price was 20-30% more.

We agreed the quality of the flag was more important than the source. We exchanged oaths of secrecy and proceeded to use the foreign-made flags. Jelleau excised the labels, burned them, buried the ashes, and planted several poison ivy seedlings in the adjacent soil.

Yes, I’m aware I’m violating the secrecy oath now. Somewhere out there, Jelleau seethes. Which is why I gave him an alias.

Rational Decisions

The point of that story is to illustrate something economists refer to as rational choice theory. When we’re thinking and acting rationally, we make choices that vindicate our interests rather than promoting particular values.

When the two are in conflict, we must be at least indifferent to the impact of competing options to choose values over interests.

In the flag vignette, had the quality of a US-made flag approximated the quality of those we got from a foreign manufacturer, and if the prices had been within a few bucks of each other, we’d have sourced from a US supplier. But given the dramatic advantage in quality and price, not to mention the sunk cost already incurred, we did what best served the interests of the unit and its membership.

If you understand this razor-simple idea, that people and organizations will act in their interests most of the time, you possess a tool capable of cutting through 99% of the rampant misrepresentation, cynical propaganda, and bloated rhetorical chicanery unfolding around us constantly.

A few examples.

This morning I saw a BBC investigative report into baby food manufacturing in the UK. See how the pouch in the example above says it’s for babies 6+ months old? That’s new. Before BBC exposed the practice, manufacturers were labeling their products for babies at 4+ months. This is contrary to pediatric recommendations, backed by science, which recommend a milk-only diet until 6 months.

The companies didn’t sacrifice the revenue upside of having these pouches stuffed into the mouths of babes two months earlier because it was the right thing to do. Had that been the case, they wouldn’t have needed their drawers pulled down on national TV to take action. They calculated that in order to avoid negative sentiment from fussy moms and to swerve regulatory intervention, it was in their interest to change marketing practices and limit their losses.

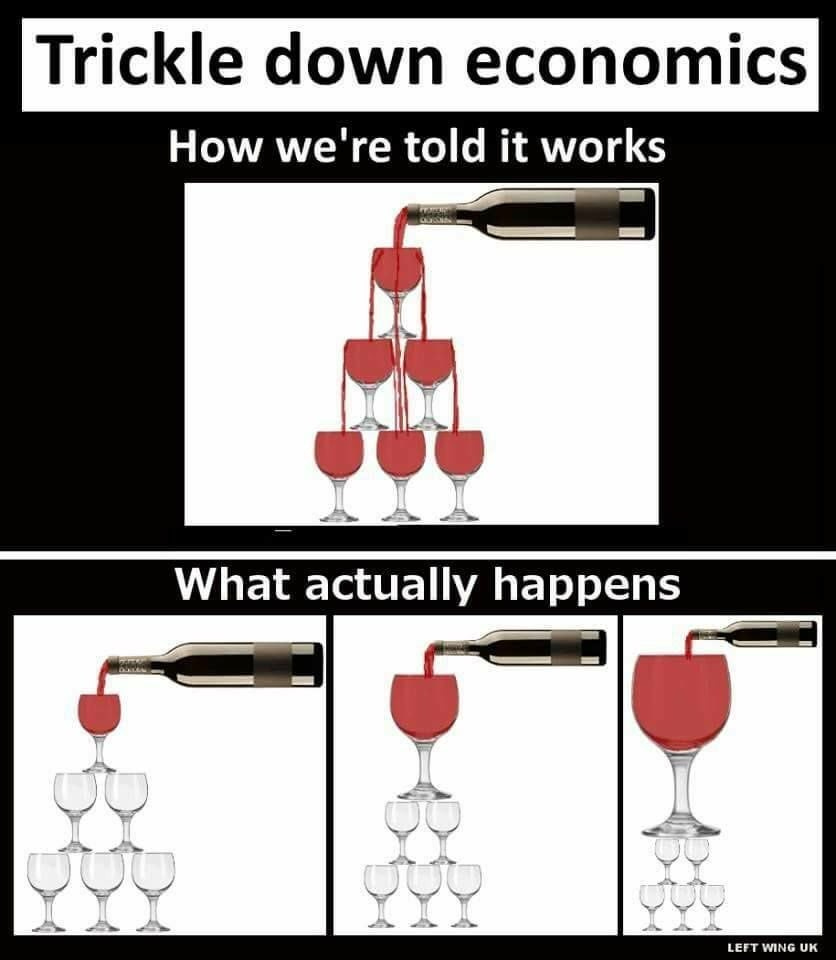

Rational choice theory is why “trickle down” doesn’t. Wealthy individuals and large corporations do not gain materially by paying higher salaries and wages to workers. They are unlikely to voluntarily devolve their wealth simply because it helps the overall economy or reduces social spending or grows opportunity for others. These are values, and will be trumped by interests nearly always.

This explains why real median wages have risen just 17% since 1984 while per capita GDP has doubled. And why the share of income earned by the top 10% wealthiest Americans has gone from a third to half of national total in that same time.

It explains why sometimes, individuals will choose to stay unemployed rather than go to work. If the costs of working will offset income enough to make them poorer, they lack a rational reason to seek a job. Shouting at them about being lazy is an appeal to values, and will seldom succeed. Just ask my wife.

Perhaps most of all, rational choice theory explains why we need regulation. Without regulatory pressure, Amazon will sell flammable pajamas. Without a legal constraint, Amazon will seize and spend unmatched 401k contributions left on the table by employee attrition. Without a legal constraint, Amazon will create that attrition by forcing people to relocate after they were hired on remote work contracts. In all cases, Amazon and companies like it will be unmoved by tiny violins plucking the mournful tunes of betrayed values.

They don’t care. Because caring costs more than not giving a shit about people. Nihilism, it turns out, is cost-effective.

Without a legal constraint, UK water utilities will pay huge bonuses to executives while dumping sewage, chemical slurry, and trillions of plastic particles into public waterways. By the time three-eyed fish with braided orange hair start appearing, the executives will have dined heavily on their bonuses and be either dead or too old to prosecute.

Without a legal constraint, lobbyists will dump multiple Fort Knox equivalents into every US election to purchase access to lawmakers and influence over legislation. And without a legal constraint, legislators will represent lobbies who enrich and empower them rather than bother with individual constituents who can do neither. Writing letters pleading with them to reassert their Constitutional role and duty hasn’t worked for a long time and won’t work now. They’re behaving rationally.

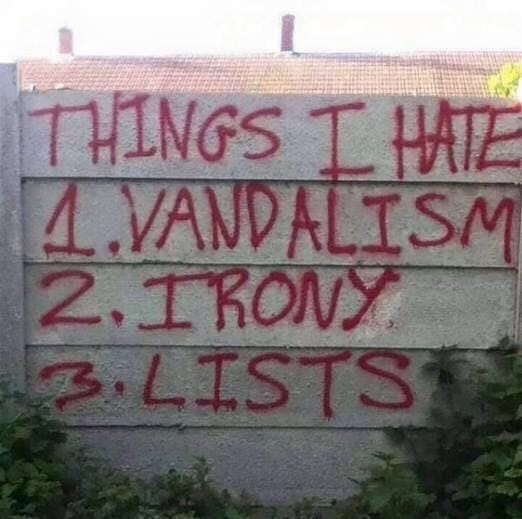

American prison populations quadrupled in the same 40-year period violent crime rates were cut in half. In that same time, the number of private prisons being run for profit exploded, with substantial slices of profit poured into lobbying. And in that same time, in an incredible coincidence, every lawmaker and their dog advocated laws to lengthen sentences for non-violent offenses, creating the need for more private prisons. Weirdly, white-collar crimes were not as popular with lawmakers as small-time drug possession, vagrancy, and vandalism.

As Americans, we’re socialized to define phenomenon in terms of moral rectitude and personal responsibility. We want to believe there is a universal definition of rightness. We want to believe in just deserts.

We think of something as “good” or “bad.” When we see something bad, we yearn for the clarity of a villain who made a heartless or unethical or criminal decision.

But most of what we lament is the utterly predictable consequence of people and organizations making rational decisions in a system that rewards them for doing things that harm others.

When we understand this, we understand that the only way to change undesired patterns of behavior is to manipulate incentives so they align with the desired behaviors. “Good” decisions then become more commonplace.

We also understand that expecting a person to work harder for the same money isn’t a sustainable position because it’s not rational.

Expecting a retailer to build a clear and easily navigable online shopping experience is unrealistic. They make a lot more money by tricking ocularly challenged grannies into buying things they don’t want and making it nigh on impossible for them to cancel.

Expecting a company to voluntarily pay sufficient wages to make welfare programs unnecessary is unrealistic. They’re happy to let the government and taxpayers shoulder the social burden, even if it creates the absurdity of people paying taxes to fund their own welfare checks.

Expecting a corporation to accept decent margins on a $10 claw hammer when they can sell it to the government for $189 is unrealistic.

And of course, expecting food manufacturers to refrain from the slow poisoning of our entire population is irrational, as they make a shitload more money by pumping us full of sugar and ultra-processed bilge than they do selling us real food. Especially if they have to pay apple pickers a decent wage instead of handing them a few bills under the table.

Are Values Irrelevant?

Does what I’m saying mean that things like norms and traditions and values don’t matter anymore? That we’re surrendering to the individual and societal anarchy of every man/woman for themselves? Is that the natural (d)evolution of rational choice theory getting deeply embedded into our frail and nebulous ethos?

I don’t think so. At least not yet. And there are two facts which illustrate this.

First, it’s still possible to deliver sufficient offense to common sensibility that people choose to exercise their meager power by rejecting something en masse.

The Q1 ‘25 Tesla sell-off is a vivid example. The company’s share price was already struggling for a variety of reasons when certain segments of the car-buying public turned their backs on the company after its CEO’s notoriously divisive involvement in national politics.

The risk becomes more acute with exposure to multiple markets and cultures, as the sheer diversity of values makes it mathematically more likely someone will be offended by something.

Second, we’re not always rational in our decisions.

When passions are inflamed, we make decisions irrationally. We respond to emotion instead of fact or theory or logic. The emotions most likely to remove us from a rational decision space are fear and anger. So when someone wants us to make our decisions irrationally, they tap into our worries or piss us off. Or both.

Immigration is an entire issue sustained by triggering irrationality in service of a rational objective. Let me explain what I mean by asking a few questions.

Does it make any sense that one of the most divisive and incessantly debated issues in American political discourse over several decades hasn’t been subject to substantial legislative reform in nearly 40 years?

Does it make sense that agents of both major political parties have proposed comprehensive, bipartisan legislation likely to fix the issue only to have it thwarted by parliamentary tactics, often from within their own ranks?

We sent people to the moon. We split the atom. We invented hot dogs and baseball and velvet Elvis paintings. We pioneered every major innovation of the Information Age. We’re Americans. We can do anything.

If we wanted to fix immigration, it would be fixed.

Immigration remains broken because it serves the interests of a great many people to leave it broken. And this is achieved by sport-bitching about it constantly, inflaming passions on all sides of the political debate, attaching it to various elements of ideological and cultural conflict to ensure it remains intractably emotional.

This benefits businesses that want cheap immigrant labor. It benefits politicians who want to fill campaign coffers with contributions freed from wallets by irrational hatred of immigration and/or responses to it.

It benefits demagogues by keeping people argumentative and distracted rather than unified with a clarity of purpose. And of course, it benefits legislators by giving them a live issue they can use as an excuse for inaction on other issues, and by preventing anyone from being accountable for the success or failure of a new legal regime.

Most polls tell us that there’s no reason for all the noise. Most of us are in favor of calmly improving things, while a quarter of us on either side are hardliners.

Now think of every hot button issue that pisses you off. Ask yourself whether it’s really impossible to fix it, or whether it remains broken because it keeps us irrational. And in doing so, supports the rational aims of others.

In a way, this reads as good news. It means we’re still in a value-based universe, where the strongest reactions come from passion and not from cold-eyed rationality.

The trick, of course, is cutting through the noise to understand where there is overlap in the values we hold dear. Where we can stand on common ground and push for outcomes and behaviors and decisions that serve our interests without offending our values, and serve our values without offending our interests.

The unfolding issue of tariffs will be an interesting test of this idea. Resting the burden of tariffs on foreign nations appeals to our America-first passions. If we believe foreign countries and their businesses, like the Chinese flag makers, have been sticking it to us, then the idea of making them suffer is emotionally appealing.

But this approach is likely to offend the economic and popular interests of foreign governments, triggering them to make rational decisions to claw those interests back. Such decisions are likely to be coercive or subversive, and likely to compound economic damage to us. Perhaps even to the entire global financial and commercial systems.

But resting that burden on the actual employers who have it within their power to revitalize American industry and employ more American workers is more likely to generate the rational reaction we seek, or claim to seek.

Whatever happens, carry with you the razor-simple idea that most of the time, people and organizations act in their best interest as they perceive it. And when they’re doing something self-defeating, they’ve been moved there by irrationality.

These are not universal truths. The only universal truth is that there is no such thing.

But they’re more true and applicable and durable than most of the braying claptrap foisted upon us non-stop. Cutting through all that, distilling the essence of what is actually going on, is an increasingly relevant tactic for modern survival.

Or so I say.

This was on my radar, now it’s on yours.

Tony is an independent writer who specializes in leadership, organizations, and defense matters, but reserves the right to spill words about whatever he damn pleases.