I.

There’s a moment of sublimely genius film-making in Fight Club. The insomnia-stricken protagonist at the heart of the story has been descending into madness, powerless to regain the mental initiative.

He suddenly realizes his life is being destroyed by his alter ego. He is destroying himself.

Surrounded by mayhem, tormented by an enigmatic and abrasive “friend” who shepherds him toward anarchy, his worldly possessions gone, he edges toward darkness.

Suddenly, the truth becomes clear. He knows what he must do to swerve oblivion disguised as liberation. His alter ego banished, he’s able to shake off the fever and see clearly again.

What a fantastic metaphor for so many things.

It’s that annual moment. The one where we reflect, or something like it. As life hurtles us along at the speed of heat, we try to slow down a tick and think about the bigger picture.

The meaning of liberty, our journey from colony to free nation, and our love for the idea of people emancipated from unjustified subjugation.

We raise these lofty ideals on flagpoles, we gather piles of charcoal, and we do what Americans have always done, no matter what.

We turn this mutha out.

Remember, it ain’t over until the fat lady sings … and files an insurance claim.

Fireworks remind us we had to fight to get where we are. They signify our cultural commotion. Our love affair with the decibel. Our attraction to mayhem.

Under a fusillade of errant bottle rockets, barbecue grills become efficient nitrate conveyors assembling magical tubes capable of translating short-term joy into long-term flab. Elvis croons from his perch of velvet immortality as thermal waves ripple through loosely confederated mini-carnivals of horseshoes, garden hoses, and hop-infused piss water.

In the digital background, social media feeds swell with exhortations of liberty, various food and frisbee chronicles, and most importantly, some of the strongest memes we will see all year.

As a US/UK dual citizen, I certainly have my favourites.

The memes are fun. But I do find myself drawn to a more serious meditation. A reflection on the ideas and values which fueled our journey to independence, and how much those ideas still matter to this day. In particular the role of civic responsibility in a free republic.

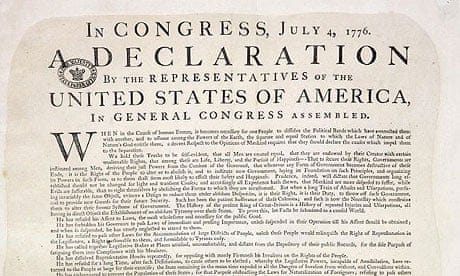

Every July 4th I reread the Declaration of Independence. Each time, I find myself awe-struck. Each time, I gain new insight.

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

These are perhaps the most powerful words in a document expressing the most powerful ideas of any political movement in recorded history.

The American Revolution started for different reasons than it carried on. But of the many tasks it sought to perform, the Declaration’s most important function was to provide a unifying collection of principles around which its movement could assemble, grow, threaten power, and eventually change the world.

Truths. As in, not debatable. The Declaration renders certain principles impervious to caveat by any man, including a monarch. Individuality is elevated and dignity is recognized. The existence of truths which transcend interpretation by the empowered is an important pronouncement.

Equal. And thus entitled to the same rights, not a lesser or greater version determined by politicians, courts, or even popular consensus.

Endowed and unalienable. Granted by nature, not by fellow man, government, monarch, or decree. The Declaration was doing just that, declaring what was already true as an element of the human condition. As distinct from a grant given by human power.

In its expression of the entitlements of being human, the Declaration of Independence lit a spark of Enlightenment-inspired idealism which has propelled the advancement of liberty, self-governance, and resistance to unwarranted authority ever since.

The world we inhabit is one shaped by this document.

II.

And yet, in its timeless beauty, to be justifiably revered across the ages, the Declaration of Independence acknowledges its own conundrum: in order to secure the equal rights granted by nature but threatened by man’s cravenness, a government must be formed with the purpose of codifying and guaranteeing those rights.

To do so, it must be possessed by and accountable to the people it protects. Those people must unify in order to preserve the right to individualize. Securing rights is a collective action problem designed to protect individual dignity.

The Declaration doesn’t and can’t exist on a legal argument for this collective action. It is not a legal document and carries no binding force. But it has a fundamentally legal purpose — declaring a legal separation.

Every revolution is plagued with these contradictions, and ours was no different. So we are left with a non-legal document which nonetheless does a much better job of expressing our core ideals than any law ever could or ever has.

This puzzle creates a persistent divide between what we believe (our values) and what is legally binding (our laws).

This gestures to one of the Declaration’s most glaring omissions: its failure to deal with slavery.

Sometimes our reverence for founding history clouds the reality of how it all actually happened. Like the imperfect ideas it expresses, our Declaration of Independence is an imperfect document. Most notably, a paragraph vilifying King George III for his role in creating the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the manner in which slavery offends the humane ideals voiced in the Declaration, was scrubbed from the first draft.

Historians will tell us that makes sense.

In context, including an open critique of slavery would have likely scuttled the consensus needed to earn the Declaration legitimacy across thirteen colonies and killed the revolution in its cradle.

But historians also concede the fundamental contradiction between the Declaration’s language and the entire concept of slavery in the colonies robbed the founding period of an important element of moral and legal clarity.

This planted a bomb in the new America. It made the Civil War inevitable, and continues to ripple through America’s divided heart to this day.

III.

What makes the Declaration special is not its position on what we now consider the headline issues. It’s the focus on ordinary issues of governance.

Popularized history says colonists rebelled because of unreasonable taxes, the quartering of soldiers in their homes, and compromised civil liberties.

This makes for a good story. But the King did not initially attempt to physically subjugate the colonies or impose his will by force. That came later.

What drove the Declaration was simple neglect. The Declaration’s complaints, far from the stuff of coloring books, are both mundane and profound.

In the text of the Declaration, drafted primarily by Thomas Jefferson in the few weeks prior to July 4th, 1776, there is a systematic list of 27 grievances against King George III.

These are the basis of the colonies’ decision to pull away from British rule. Here’s a snip of the first nine.

Let’s assume Jefferson prioritized in this list of grievances those which were most objectionable to the colonies, and that others agreed during its revision.

That would mean these nine grievances, one third of the those enumerated, are the main causes for the Revolution.

The King, says Jefferson, refuses to pass laws, agree to laws, or empower his colonial governors to make laws.

The King refuses to support or facilitate legislation. The King is fixing elections, appointing his cronies to judgeships, and refusing to allow anyone not beholden to him to occupy a legislative or judicial post.

These are not complaints about physical intimidation or the quartering of troops.

These are complaints about basic governance.

The impacts mentioned and alluded to here are not about some comic strip version of jack-booted physical tyranny characterized by violence and military impunity.

They are concerned with the disorganization, economic chaos, and unstable expectations resulting from the King’s failure to orchestrate adequate rule. The colonies are no longer properly represented, and their attempts to represent themselves are being undermined.

No longer willing to tolerate these impacts, the signatories insisted on their own governance. They considered it a duty of civic responsibility to fellow colonists.

This brings me to how little has changed.

Or more accurately, how much we’ve let back-sliding, inertia, and various incremental excuses and exigencies pull us backward in time.

Public trust in government is at an all-time low. Our form of government provides that citizens will be represented in a bicameral legislature, with elected Representatives responsible for the advancement of local interests at the Federal level. But, as is becoming broadly obvious, our representatives don’t represent.

Representatives today do not govern, continuing a pattern stretching back a few decades. The preference now is to engage in divisive rhetoric on hot-button issues, thereby getting everyone pissed off and distracted so they don’t notice legislative malaise.

This drives electoral funding while pushing Americans into factional tribalism over marginalia impacting slivers of the population. The big, boring, procedural aspects of administering the world’s most consequential nation go untouched, and virtually no aspect of American life is properly understood, supported, or regulated by its governing bodies.

Few meaningful laws get passed. Important economic and social issues languish until courts are forced to resolve them or (more often) the executive branch fills the power void by issuing legally-binding orders or re-interpreting laws to give itself the authority to move forward.

When Representatives do get energized to push or obstruct on particular legislative issues, they are nearly always acting on behalf of a special interest which has lobbied them for support, fattening their re-election coffers or extending some other form of less obvious but perfectly legal political payola.

In other words, we are suffering from a lack of basic governance.

Americans are under-informed or misinformed about how government should work, and therefore far less outraged about this morass of ineptitude than they ought to be.

As a nation, we’re painfully oblivious to the issue of campaign finance and money in politics. It is perniciously insidious and corrosive to our way of life. Many devoted patriots have tried to tell us, but the message is not burning through.

But the presence of money in politics, as corrosive as it has proven to be, is not our biggest problem. Indeed, the reason I wring my hands between shovel-fulls of potato salad this Independence Day lies a lot closer to the original reasons we needed a Revolution in the first place.

Some problems are timeless, which is what makes a timeless document like the Declaration so important and so durably insightful.

IV.

The link between ordinary Americans and our Representatives in Congress is broken. We’re not listening to them, and vice versa. Apathy looms large after decades of institutional decay. We’ve lost confidence in our government. We’ve fallen a long way since the pledging of sacred honor.

Matter of fact, I can’t remember the last time I heard a US politician use the word honor with a straight face.

The good news is that those who built our system of government had a plan for this moment.

They gave us a House of Representatives to make sure the voice of the general public was never drowned out by wealth or aristocracy or unwarranted control of the Federal agenda. They then gave us the freedom to express ourselves, making sure we could speak and someone would be there to listen. In this way, they made sure we could grab our government by the scruff, carry it back to where it belonged, and tell it to behave. It would be bound to listen.

That remained more or less the case until 1911, which was the last time Congress discharged its Constitutional duty to reapportion representatives according to updated district populations.

Every time a census is recorded, Congress is duty-bound to reapportion. This provides a ratio that guarantees a popular voice. Starting with the 1920 Census, Congress refused to reapportion, citing immigration, farm labor patterns, and urban growth. The concern was reapportionment would disadvantage Southern states and create a rural-urban divide capable of killing the Republican party.

So instead of solving the problem, we just stopped growing the House. Since then, the population has more than tripled. Among nations with legislatures, only India has a less equitable ratio of citizens to legislators.

Now throw in redistricting and gerrymandering.

Now throw in unchecked lobbying and dark money in elections, which encourages legislators to listen to funders at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Now throw in 24/7 outrage media that collects revenue by persuading us government is the problem. Not our tool to guarantee our rights as Jefferson envisioned. Not a method of withstanding the inherent pressures of collective action combined with human nature, as Adams counseled. Not a means of securing tranquility, as Washington fervently hoped.

We are now persuaded government is a threat and an opposition.

And that’s in the brief moments media isn’t punching us in the amygdala, stoking irrational fears of all sorts. A hellscape teeming with criminally inclined immigrant gangs. Insect swarms everywhere. Thieves lurk in every church, rapists at every highway rest stop, brainless drug addicts probably peering through your kitchen window even now.

Vote for us and increase your credit limit. All will be well.

Truth is hard to come by, and diluted by undeserved doubt even when it presents itself.

Surrendering to the merciless corporate march of profit uber alles, media agents have transformed themselves into hate machines spewing opinion stripped of facts, which are like gold dust.

They’re doing what sells. Which makes it our fault, because we’re buying it. Except some of our reactions are involuntary, neuro-chemical realities they’ve tapped into using the dark advertising art of mental manipulation.

We are sat at a table where a media waitress incessantly tops up our plastic cup with irresistible, bias-confirming misinformation packaged not just for easy digestion, but for hardcore addiction.

The few outlets still attempting to report truth are sparse flickers in a hurricane of confusion-spiralling wickedness. Lies sold as truths, adopted as gospel, and chambered in the guns of the culture war.

We are in a post-truth era, where facts are redefined to suit agendas. Terrifyingly, Americans go along with this because it suits us ideologically. No one knows what to believe any more, so they believe what feels right.

Is it any wonder we’re confused, insecure, and borderline hysterical most of the time?

And amid the din and confusion, our House refuses to represent us, or to even equip itself to properly do so. This can only mean the incentive to represent has been superseded by incentives to the contrary.

Which sounds familiar.

Because that’s what happened all the way back in the 18th Century. This is not a new problem. It’s not a King this time. But it’s doing the same thing that was done to us before.

We’re not facing jackbooted thuggery or physical subjugation at the point of a bayonet. Only an insane idiot would instigate a population with more guns than people and a serious beef with politicians.

We’re in trouble because of ordinary issues of governance.

History may not repeat itself, but it rhymes. We’re deep in a rhyming chorus at this moment in time.

V.

So we are lacking in proper representation, and the accountability mechanism to help us see and act on this problem is broken, kicked into the tall weeds of capital-driven free expression divorced from its purpose.

Even if the media woke up tomorrow and regulated itself, it would take Americans decades to believe in anything it said again. Even longer for that confidence to extend to Congress and other institutions.

But even those thoughts are fanciful. We’re still in afterburner heading the wrong way. That will remain the case until we muster the collective will to grab our Congress by the scruff, insist that it reapportion so it can hear us again, and then start telling it what we expect.

I see no evidence that we are within light years of such a thing.

Which makes it fair to question whether we are making proper use of the freedom we’ve been given at great cost to others.

VI.

America’s revolutionaries acted out of civic responsibility. They were unwilling to bear the erosion in humanity and breeding of chaos they saw as handmaidens to a vacuum of power.

The problem today is different. There isn’t an all-powerful King preventing us from governing ourselves.

This time it’s on us. We’re the all-powerful. We own the government. We are its legal guardians. We pay for it. Our votes determine who is in it. And with the rise of social media, we have a louder voice than ever before.

For any of this to matter, we have to overcome our selfish views, discard our biases, shut out the hate fed to us by those who profit from spewing it, and regain our own representation.

We have to get back to the basics. Support when we agree. Oppose when we disagree. Form opinions based on evidence. Form opinions without considering what one partisan faction or another says we should think.

We have to think for ourselves.

Which is what the OG Revolutionaries did. They said to the King “hey, we’ve been thinkin’ about some stuff,” and then told him how it was going to be. No one in the world would have predicted anything other than a total slaughter of the rebels, capped with a ritual at the gallows to deter others.

Against all odds, they navigated a minefield of violence and civic ambiguity to bring order to a new nation.

We have to do something similar now while learning from the King’s mistake, which was refusing to resolve matters peacefully.

Every system ever built to protect freedom is under attack from the moment it is born. The civic duty of its participants will determine how long it can survive between rounds of upheaval, sometimes marked by bloodshed.

George Washington understood that. He believed an informed and civically active public was the only lasting bulwark against the march of power.

During the Constitutional Convention, Washington held his cards close. He remained objective and wanted to be seen that way. Not only because he hated political parties and their inherent stupidity, but because he was eager to set an example of calm, thoughtful leadership.

He became vocal during one particular Constitutional debate. Reapportionment. We have Art I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the US Constitution because Washington was insistent it be there.

But it’s not in the Bill of Rights. In 1929, Congress saw fit to ignore Washington’s timeless advice and give themselves the legal latitude to ignore this clause.

That was a mistake. Surely we see that now. While we don’t need to stick with Washington’s original ratio and have a House of 11,000 representatives, we needn’t stick with 435 until it becomes terminally evident doing so can kill us.

VII.

Have we been sleeping?

Have we slept?

Because as I look around now, there is a sudden realization that the problems we have are not posed by foreign governments, deep cover operatives, deep state conspiracies, or unholy round tables of malevolent billionaires.

It’s just us. You and me. We were handed the tools of representative government. We’re not exercising them. In our hypnotic torpor, we’re boosting Cheetos and freebasing Revolutionary nostalgia while shit goes awry.

This invalidates two unspoken assumptions of the Declaration of Independence.

Citizens who are civically engaged.

Public officials who are responsible and know citizens will insist upon it.

The next few decades will reveal whether we are capable of recapturing our founding spirit and rediscovering our will to be as civically responsible as those who ignited our march to freedom. Even when it feels routine, mundane, or tedious.

Or whether we are too far gone.

Either way, may the memes, fireworks, and hot dogs continue, preferably with a rock-n-roll soundtrack.

Tony is an American writer and veteran.

I found it interesting that you spelled shit Shite.

Are you reporting back to the MI5 or the MI6?

Maybe we need to look into your background and your connections.

So which is it Sir Carr?

Are you an American or are you a Brit?

If you are more loyal to the Brit's you need to be returned there.