Lessons from an Untenable Situation

A storied club fires (a)nother manager, exposing leadership lessons aplenty

Recently, I asked my Amazon Echo device “who is the current manager of Manchester United Football Club?”

It replied “Erik ten Hag.”

After a decade of stumbles and around $25B in flushed investment, Amazon still hasn’t learned how to field a device that can provide up-to-date information. Manchester United had fired Erik ten Hag hours before.

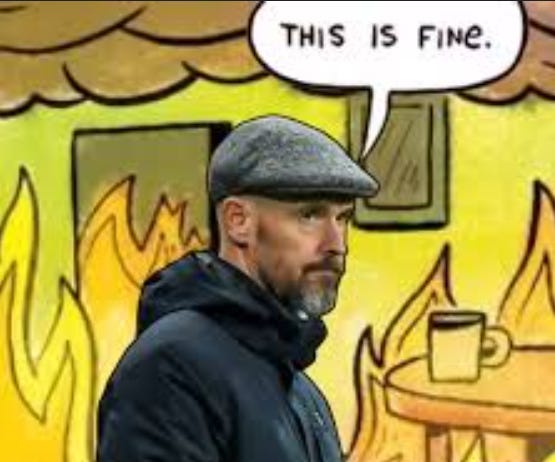

He’d lasted two-and-a-half years and won two trophies, but guided the team to only three wins and 14th place in the Premier League table after nine matches in the current season.

By club standards, it was an unthinkable situation, and an untenable one for ten Hag. The decision was clearly driven by unsatisfactory results.

But we can learn a lot by asking one more why to get beneath the skin of those results. Why couldn’t this particular manager get more from his team?

This isn’t a question we can typically ask, and is therefore a rare gift.

Rare Transparency

Usually, when a high-ranking manager or executive is fired, we can’t learn much because the reasons are shrouded in secrecy. The US military famously rubber stamps every sacking with “loss of trust and confidence,” which conceals what actually went down and prevents anything useful being learned.

Think about that. In any given year, approximately 10% of those carefully developed and competitively selected to become commanding officers lose their jobs.

Sometimes, it’s because of misconduct or criminality. But far more often, it’s for reasons of performance or style. And no one can learn from it, because the facts are not shared. They’re not rolled into case studies and taught in schools. They’re not studied and fed back to human resource administrators. Best we can tell, there isn’t any data tracked by anyone.

Which is why we should be especially energized to learn all we can when there is an opportunity. For the hapless ten Hag and others who occupy managerial roles in the public domain, this means they are subject to a post mortem others are able to swerve.

But before outlining what I think we can learn from Erik ten Hag’s failure at Manchester United, it’s worth stipulating that the club’s predicament cannot be laid solely at his doorstep.

Disunited

I wrote back in May that I believe Manchester United hasn’t learned to build the right habits of thought and action since Sir Alex Ferguson concluded his tenure 11 years ago. Partially because it grew too reliant on Ferguson’s personal touch and didn’t manage to translate his presence into a culture that could outlast him.

The ten Hag debacle continues the trend. His main contribution to the club seemed to be devising solutions to tactical problems and recruiting players who could make those problems more manageable.

He worked by episode. There didn’t seem to be an identity, vision, or thread running through it all.

Ultimately, he didn’t get satisfactory results. The question is why. And I see three standout lessons as intriguing as they are universally applicable for managers and leaders in any organization at any level.

What ten Hag Can Teach Us

The best way to learn is from someone else’s hard times. It beats the cliche of mumbling under your breath as you lug office trinkets quietly out the back door of your workplace in a nondescript cardboard box.

Erik ten Hag’s hard times give us three things to think about. Three things that, if mishandled, can get you fired.

(1) When it comes to accountability, you can hold or be held.

When your people come up short despite being well-resourced and properly supported, it’s a moment for accountability. To reinforce standards. To renew expectations. To drive an appropriately hard bargain.

Sometimes, leaders don’t take this path. Whether out of charitable spirit, misguided empathy, or personal affection, they hold back the hard words. They bypass the uncomfortable moments. They throw their arms around the team.

Depending on the circumstances, this can work sparingly.

But it’s a poor choice of default. Most often, it denies the team the form of support they need, which is the healthy and clarifying pressure to inspire them back to expectations so they deliver next time around.

One of the best military leaders I ever knew cut off the fuel to his own career by being soft, both in perception and reality, when his team failed to deliver in a high-profile operation. He blamed bad luck and bad weather, when the real story was about bad planning. Complacency led some of the most elite performers on the planet to get key things wrong, and costly failure was the result.

He didn’t hold his squadron accountable. So he was held accountable by the promotion board. He was never promoted again and never commanded again. Had he held his team to account, and kept the right distance to do so in the first place, he’d be part of the Air Force’s senior team today.

So far this football season, no team has missed more big chances than Manchester United. The manager’s tactics and selections are producing an open net, and players are failing to put the ball into it.

And yet, you wouldn’t know it from ten Hag’s public comments. He constantly insisted the team was progressing, moving in the right direction, following a gradual process that would eventually produce winning results. In his final press conference, he blamed their fresh loss on bad luck.

His comments match his actions. Players who make key mistakes didn’t get benched. They were publicly congratulated for their efforts. Bruno Fernandes went 13 matches without scoring and cost the team dearly with his on-pitch indiscipline.

Yet, he remained a lock for selection every match and was seldom subbed. Other managers, more successful ones, are not afraid to bench a superstar who needs a reminder of mere mortality.

Players missing the goal when they shouldn’t isn’t something ten Hag could have fixed himself. He can set players up to succeed, but they have to do the rest.

However, when they fail to do so and he is seen to be coddling or assuaging, he adopts their performance. It becomes his. And he pays the price for it.

This is the choice for every senior manager. You are either seen to be holding your people to account, or you are seen to be part of the problem.

If the former, you’ll be given time to sort through issues and get on track. That time could be considerable if you’ve laid the groundwork. If the latter, you’ll be pushed aside in favor of someone perceived to be tough enough.

As a footnote to this lesson, be wary of the trick of talking tough publicly but accepting excuses behind the scenes.

First of all, if you’re not exercising accountability but simply covering for your team, you’re not a leader. You’re a cheerleader. You’re not making them better, so they will continue to struggle and eventually you’ll be found out.

Second, this signals your team you prefer duplicity to unpopularity. Which means you don’t care nearly enough.

Whether ten Hag privately held his players accountable, we don’t know. What we do know is that publicly, he tried to paper over their performances with excuses, and they didn’t get better.

He adopted their performance instead of improving it, and paid the price.

(2) You get more of what you recognize, and less of what you don’t.

For large swathes of the past 18 months, Alejandro Garnacho has been United’s best player. He’s provided more creativity and attacking threat than anyone else. He’s unsettled defenses, forcing them to adjust, often creating exploitable gaps. And he’s hustled non-stop, making defensive recovery runs, fighting for every loose ball, and putting his body in painful positions to fight for possession.

For these sins, he found himself benched several times. When ten Hag was asked about this publicly, he chose words downplaying Garnacho’s contributions. He framed the player as still having a lot of work to do to be excellent at the highest level.

Failing to recognize a player’s efforts and results send them the signal nothing they do matters. Their effort level is likely to drop as the fire in their belly cools.

Meanwhile, someone who wasn’t performing as well got to play anyway, which sent the message that you can get out-hustled, out-run, and overall out-competed and still get plenty of opportunity.

Few things are more powerful in an organization than the recognition a leader gives. In a situation where your best performers feel under-appreciated, they will slow down. This won’t get cancelled out by lesser performers speeding up, because they got their recognition without needing to do so.

Getting recognition wrong throttles performance.

In 2022, I launched a new warehouse for Amazon in its UK operations network, a project valued at about $300M. I worked to set a tone of frugality, reminding every stakeholder that we were launching during a time of slowing growth, and needed to be responsible with increasingly scarce resources.

My team and I saved the company several million against projected launch costs. I was happy to accept the thanks and congratulations of a dozen senior leaders who heralded our efforts as we crushed our first peak season. I was rated a “Role Model” on Amazon’s leadership principles.

But when compensation review came around, my total earnings were decreasing year-on-year. There were esoteric reasons given for that which amounted to dry shit. They’re a great story for another time. But the bottom line is I didn’t feel recognized. Had I launched another building the following year, how motivated would I have been to invest the extra hours and effort to police avoidable cost? To innovate training and hiring methods? To carefully study shipping and storage value streams and innovate them to reduce waste?

The next round of launches didn’t go as smoothly. The message was clear that the professional juice wasn’t worth the personal squeeze.

(3) Without relationships, you are dead.

There’s an old adage in the long-haul aviation business. “There’s a jackass on every crew. If you don’t know who it is, it’s you.”

When you don’t cultivate relationships, you get isolated. You lose awareness of the key details you need. As situational awareness erodes, you’ll make inputs that don’t align to the circumstances, often making things worse.

Erik ten Hag struggled to build relationships with his players. The public chafing over Garnacho’s performance was a continuation of melodrama from the prior season, when Jadon Sancho was benched, separated from the team, and eventually loaned out to a German club after a falling out driven by public criticisms from ten Hag. Regardless of the substance of those critiques, the manager let them alienate him from a player the club had invested heavily to acquire and develop. Sancho ended up back in the league this season with Chelsea, and performing at a high level.

Club hero Scott McTominay was sold away over the summer.

Club legend Cristiano Ronaldo was benched and marginalized, eventually leaving in a bitter episode that ended his storied run in the worst way and cost the club millions.

Marcus Rashford scored 30 goals two seasons ago, and this season can barely break into the starting eleven. He plays without joy, his non-verbals telling a sorry tale.

Harry Maguire went from top of his game to disgraced, his confidence shattered and prospects diminished. This was England’s premier central defender not long ago. Under ten Hag, he got worse, with players he once overshadowed since brought into the club to compensate for his faded contributions.

The picture painted is grim. The manager evidently struggled to connect in even the most basic way with people who shared his goals and wanted to succeed under his hand.

I’ve seen this play out many times in my own journey. In ‘17, I crossed paths with a General Manager at Amazon who was tough, competent, and had a reputation for driving high standards. Over the next year, a clear pattern emerged. When things were going well, he was affable and easy to approach.

But when things didn’t go well, any perceived connection was exposed as superficial when he turned on the team like a wild dog. Public criticisms spilled over into insults and toxicity. Morale plummeted. And before he knew it, this individual was orphaned from his own inner circle, having pissed everyone off.

After that, when things went sideways, he had no way to recover. No one to work through with corrective inputs. It became obvious to the relevant executive that there was a huge problem keeping this fellow from running his building effectively.

The ensuing intervention managed to restore a decent and workable set of relationships, and the leader actually survived with his role intact. He was the exception, and only got the chance because he was humble enough to admit he’d created the problem and to ask for support.

Most times, if you put yourself on an island, you’ll die there. In professional terms, if you make yourself irrelevant to your own team, you will become officially irrelevant to them soon enough.

Conclusion

We don’t get to learn from leadership failure very often. Most times, leaders are considered symbols or icons of the organization, so to publicly expose their shortcomings reflects poorly on the organization. For this reason, their sackings are back-door departures shrouded in vagary.

Which is why we have to seize every lesson we can from those we do see.

Erik ten Hag was in an atypical role in a unique set of circumstances, but the failures we can make out from his tenure are common. Which makes them useful insights for you and me, and for anyone in the arena.

Tony is an independent writer with a three-decade background in leadership comprised of both military and private sector experience. He writes from his home in the UK.