Whether you are a Fortune 100 CEO, a small business owner with five employees, or a flag officer with a hundred thousand people in your command, this message is for you.

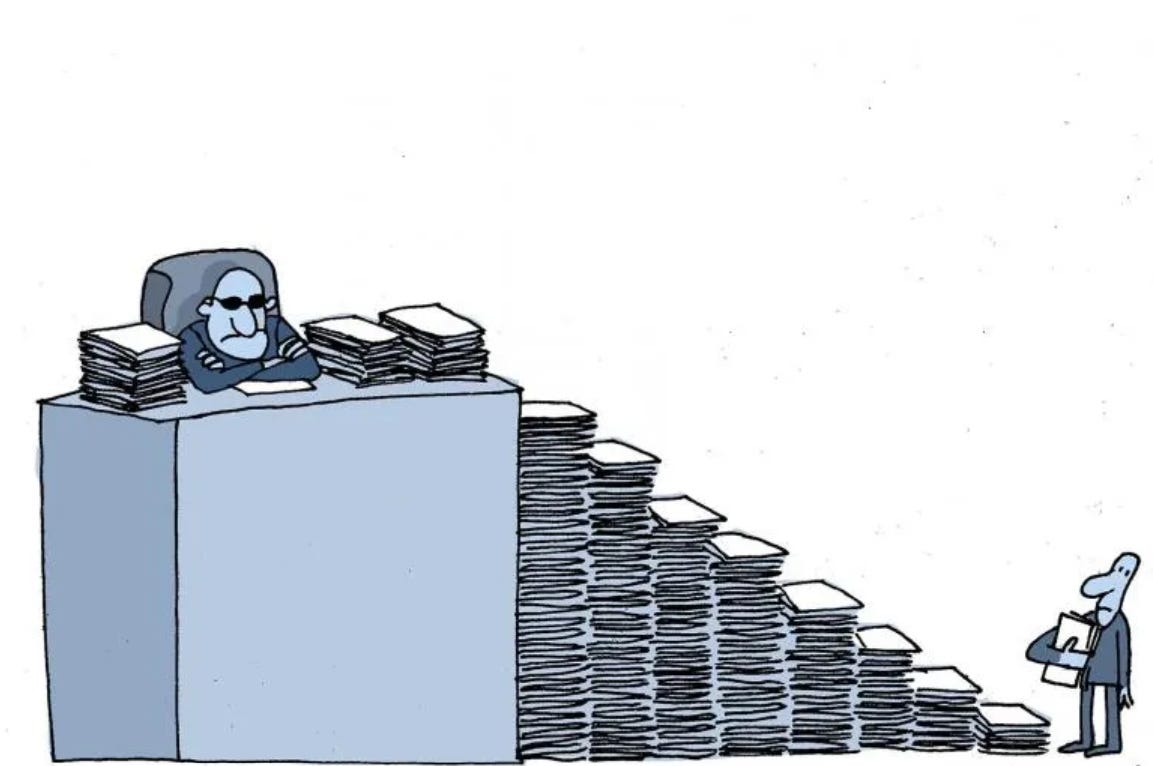

Processes, rules, and policies are terrible proxies for leadership.

We love to create bureaucracy as a substitute for leading, an attempt to expand a leader’s personal surface area. But in doing so we plant the seeds of our own suffering and failure.

Bureaucracies are regarded as legitimate organizational forms, but they are actually just ornate jails within which we incarcerate joy.

Nameless and devoid of mercy, they are where logic goes to die, first tortured until all hope is gone.

Bureaucracies …

Make the simple difficult, and the difficult impossible.

Assassinate common sense, ask questions where conclusions are obvious, and draw conclusions where questions should be asked.

Create policies for how to interpret rules and rules for how to interpret policies. When in doubt, they generate multiples of both.

Maybe I’m being too subtle. I wouldn’t want my hatred to come across as mere disdain.

So let me continue the digression.

Permission to chew bubble gum in a bureaucracy involves talking to sixteen people and getting twenty signatures. All from people whose jobs are crying out to be automated.

Bureaucracies claim to be about efficiency, but the only thing efficient is how quickly one faceless minion passes you on to the next.

Bureaucracies diffuse authority into little tiny fractions until no one is accountable for anything.

They are the origin of the phrase “who do I see about this?”

And yet, bureaucracies grant authority so generously that it rests in the hands of innumerable morons, who exercise it to inflate their own importance at the expense of doing what is clearly and obviously sensible.

And because so many rules and policies have been created, such morons will encounter no trouble in finding cover to legitimize their absurdity.

Bureaucracies do not distinguish between customer and adversary.

Both are regarded the same, but customers are treated worse because they demand more.

These serial burglars of fun can be depended upon for two things: (a) lethargic handling of any request, and (b) its eventual refusal.

Unless you asked for something you didn’t want.

If a well-functioning organization is a flowing field of green grass symbolizing harmony, intersectional interests, and breezy communion, a bureaucracy is more like a peat bog. A dank morass teeming with degeneration, unlikely to yield any constructive output until it’s been left to rot for another thousand years.

And yet …

We accept that an organization which reaches a certain scale must bureaucratize unless it chooses to break itself up.

Although we don’t sit together and deliberately say “let’s create something terrible,” … this is exactly what we do by the incremental addition and multiplication of rules, processes, job titles, and cubicle farms.

In the fullness of time, these growths form a dense thicket of red tape impassable by mortal means.

Still, we keep taking this path.

Because despite claiming to love freedom elementally, we fear the non-linearity and disarray of a liberated organization. We sense a need for administration to maintain order as activity grows.

Without firmness of order, we worry that actions insufficiently directed will diverge chaotically.

We also worry that size exposes us to more liability, making us more assailable. We become risk obsessed, creating mechanisms to protect us.

What we don’t realize is that such cures are worse than diseases.

Because once we legitimize the attitude and culture which accompany bureaucracy, misery follows. The lived experiences of people operating within it become misaligned from the values we state and intentions we harbor.

For example …

Not long ago, I told an uplifting story of Gen. Mike Minihan recognizing the combat excellence of mobility airmen and their commanders during Allies Refuge, the evacuation of Afghanistan.

Minihan took a personal interest in affirming the contributions of these airmen. He made certain they knew the value of what they had done. His leadership elevated the spirits of everyone involved, and filled the hearts of everyone watching.

But there’s more to the story, and it’s not so inspiring.

It turns out those decorated by Minihan, and scores of others involved in Allies Refuge, were not initially recognized as they should have been.

In some cases, because of the wrong people being in command roles, medal nominations were not submitted at all. This is what my Dad would have called a “cryin ass shame.”

In other cases, nominations were submitted but declined because the individual and/or deeds performed did not meet “requirements.”

According to who, you ask? A bureaucratic committee.

Applying made-up criteria layered into overgrown rule books over two decades, a “review board” comprised of mid-level functionaries who have never met the people involved and wouldn’t know an operational mission if it sucker punched them … sit in an air conditioned office and pass judgement.

They don’t pick up the phone to resolve ambiguity or ask for clarification. They’re not solving for yes.

They’re not in the business of recognizing warfighting airmen. That’s the business of leaders. Bureaucrats won’t lead, which is the whole point. They are a terrible proxy for leadership.

Medals boards are “grading paperwork.” And when one of the myriad rules isn’t met, or they can resolve ambiguity in favor of their non-combat biases, they simply stamp it denied and move on. It’s not like they’ll have to confront the commander they’ve insulted.

Except when that commander is Mike Minihan.

At some stage of these recent proceedings, and I don’t know exactly when, Gen. Minihan got word that the heroes of Allies Refuge were not being given the medals they deserved.

From what I understand, he was pissed off.

The general immediately rallied his team and got into the issue. In what’s been described to me as “taking a flamethrower” to the process and those lording over it, he basically insisted everyone get a grip.

The proper nominations were generated, routed, approved, and presented. Proving that the original resistance was completely unfounded, and just more chicanery from pencil-clutching losers who are on medals boards because they’re not in specialties for which a warfighting demand exists.

In the time it took for a leader to right this wrong, a clutch of exceptional airmen had their faith in the Air Force and its leadership needlessly tested. None could be blamed for pushing in their chips over this issue should they so choose.

I reckon some did, and I reckon others came close. For others the jury is still out.

None of this happened because of malign intent.

It happened because of two things which don’t conspire to create shite consequences but often do.

First, the use of proxy mechanisms for proper leadership, and second, leader neglect of such proxies when they run amok.

A “medals board” only exists because some well-meaning jackass created it back in the early oughts.

Back then, everyone was doing unprecedented stuff, medals were flowing freely because everyone was a superstar, and some star-spangled curmudgeon felt the need to tighten the lid on the cookie jar.

Thus, a bureaucracy proxying for leadership was born.

And then, over the course of two decades, lazy or incurious or cowardly leaders accepted increasing levels of medals board fuckery as an immutable input condition.

When I took command, my team and I committed ourselves to continuing what our predecessors had started, which was to make the 14th Airlift Squadron the most capable C-17 airdrop crew force on the planet.

And we did. And then we deployed.

And in the summer of 2011, in 129 days of operations, our single squadron delivered 22% of everything dropped from the sky into Afghanistan across the entire year.

We pioneered new tactics, opened new drop zones, forged new partnerships with ground forces. At a time when the Army wanted soldiers off roads and out of convoys, we supported with thousands of tons of sustainment on time, on target.

We re-supplied troops in contact, preventing them from being overrun when under direct enemy assault.

All done safely, professionally, dependably.

And when our tour was done, half the medals submitted were disapproved or downgraded. My boss actually called me to apologize that the medals board had screwed us.

Not enough days in theater. Insufficient grade for the medal to be given. Narrative doesn’t contain five unique facts distinguishing the achievement. Requires 3-star endorsement and we decline to request it. Current commander says no more of these for a while. Block 14a improperly annotated. Objective area not defined in command register.

The reasons demonstrated a breathtaking disconnect between those of us fighting and others over-indulging in playing referee.

It was one of the hammer strokes on the final nail in the coffin of my decision to retire from active duty. When we won’t recognize people properly, we will leave them under-appreciated. Which is not only the fastest path to mediocrity, but just wrong.

Whether you are a Fortune 100 CEO, a small business owner with five employees, or a flag officer with a hundred thousand people in your command, this message is for you.

Processes, rules, and policies are terrible proxies for leadership. Don’t create new structure or administration as a substitute for your presence.

Instead, provide your intent, drive your values, sustain your desired culture, and trust people to get the decisions right. If they don’t, they’re the wrong people for the job.

Individual humans are usually wonderful. But when we get together in groups, we’re capable of really dumb behavior, because we accept, encourage, and reinforce popular positions even when they are clearly decrepit and wrong.

None of us is as dumb as all of us.

So choose to lead. Trust other leaders to lead on your behalf. Make bureaucracy the tool of last resort to achieve your objectives. Because bureaucracies are like gremlins. Feed them and they will multiply in the dark, eventually turning on their owners with homicidal nihilism.

It is a stain on the US Air Force that legions of airmen have gone under-recognized and under-decorated for what they gave to the war effort.

They may say they don’t care about medals, and they may mean it. But in so saying and believing, they are trusting those who should care to get it right.

I’m happy the tide was turned in this instance. But I am aware of many others to the contrary.

We’re still a long way off.

TC is a retired Air Force officer with both a seething hatred and a deep comprehension of bureaucracy.