On American War

As we honor Vietnam Veterans, we should also acknowledge how little we've progressed in our relationship with conflict

This week, America honors those who fought in Vietnam. And it should make us pause and think.

Quoting Viktor Frankl, an Austrian survivor of the Holocaust who went on to found an entire school of psychotherapy based on the search for life’s meaning, Vietnam veteran Max Cleland said:

“To live is to suffer, and to survive is to find meaning in something. For those of us who suffered because of Vietnam, that’s been our quest ever since.”

Cleland contributed these words to Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s excellent documentary The Vietnam War back in 2017, about four years before he died.

A politician active on matters of war and peace and an ardent supporter of the veteran cause famous for the phrase “war is not over when the shooting stops,” Cleland represented a generation of veterans whose voice is fading from the American conversation. Today’s youngest living Vietnam veterans are in their mid-70s, and by now they’ve watched their country repeat many of the mistakes for which they suffered.

It’s at this point I will personalize to a degree, which will crystallize why March 29th and the war it commemorates have a way of bringing this issue home.

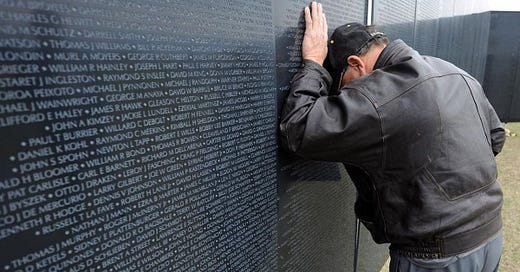

The picture below is my Dad, Sgt. Dale Carr. He was drafted into the war straight out of high school and deployed in 1968. Deeply opposed to war and violence in general, he nonetheless answered the call. He fought in Pleiku province, carried an M-60 for his squad, and came home half-dead with malaria, his spirit broken from watching his best friend die in combat.

That’s about all I know, because he seldom spoke about the war, even in the ripeness of time as we stood on common ground as fellow veterans. When the subject was breached, the room went cold … a wicked wave of turmoil visibly washing over a man who exerted massive energy to bury his feelings about his time “over there.”

Dad died in 2019. The demons who climbed aboard his shoulders in Vietnam followed him into his grave, and the wounds he suffered there chased him into it prematurely. His mood, his temperament, and his worldview were shaped if not wholly defined by the short time he spent in Vietnam during his formative years. This speaks to the depth of the trauma he experienced there, an experience representative of the millions of young Americans called into action.

While the war took half a century to drag my father down, it was more swift and merciless with many others. 58,300 Americans gave their lives, falling in the shadow of the estimated 3 million Vietnamese soldiers, insurgents, and civilians killed on both sides of the divided nation. This death toll doesn’t begin to touch the actual damage in despair, disruption, instability, and massive upheaval triggered by this generation-spanning bloodbath.

The war has been collectively felt as a national wound, and later, a national scar. It has echoed across generations as a sorrowful warning: avoid war at all costs, because once unleashed, it brings Hell to Earth.

To oversimplify, America’s involvement in Vietnam was a costly geopolitical misadventure. It began as a misguided attempt to confront and harass the spread of a threatening ideology. It continued on the steam of outright lies from generals and politicians falsely portraying it as a worthy and successful cause because it was in their interest to do so. And it was guided into catastrophe on the rails of absurd divergence between goals and resources, between rhetoric and reality, between principles and actions. As the war unravelled, so too did the American conscience, and so too its sense of unity and collective greatness.

After thirty years of scarring and a seeming embrace of Vietnam’s lessons, America felt different; as though the wisdom of the war had made its mark. Enmity for the soldier was replaced by love and respect. Generals in senior positions advocated war policies which recognized the limits of military force and demanded exit strategies before considering its use. Veterans of the Vietnam experience populated senior posts in government and diplomacy, forming a vanguard of cautious sobriety.

And then, in the space of one terrible day in 2001, the entire body of lessons we observed was intellectually shoved off the table. Turns out those lessons weren’t written in blood or carved into stone. They were scrawled on an etch-a-sketch which was summarily shaken clean the instant we perceived the fresh spread of a threatening ideology.

And so the cycle began anew. Not one but two costly geopolitical misadventures. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began as attempts to confront and harass the spread of a threatening ideology (an earnest attempt in the former, specious in the latter). They continued on the steam of outright lies from generals and politicians falsely portraying each war as a worthy and successful cause because it was in their interest to do so. And they were guided into catastrophe on the rails of absurd divergence between goals and resources, between rhetoric and reality, between principles and actions.

This time around, there was no broad sense of national shame. No unravelling. These wars were experienced by a tiny sliver of the population and were fought entirely by volunteers. Americans were not taxed for them. Americans didn’t even vote for them in any meaningful sense given that both major political parties endorsed the conflicts.

While it’s great that soldiers haven’t been spit upon or cursed at the airports and Americans are not biting at each others’ necks (over this issue anyway) … it’s alarming that twenty years of elective war at a cost of 900,000 human lives and $8T have not managed to stir anything close to an appropriate level of national debate.

In fact the main news story on Vietnam Veteran’s Day this year had nothing to do with war. Instead we were transfixed by a fake debate over whether discussing Michelangelo’s David in schools is somehow sexualizing the education of our young people. This is a silly dishonor on a day solemnly intended to house the opposite. Though admittedly, it evinces a level of inexplicable and confounding contradiction normally reserved for the innate madness of war … and gives a level of underserved focus to the irrelevant and banal reminiscent of the pathologies common in bureaucratic war machines.

But rather than asking “where did the Renaissance sculpture hurt you?” … I believe we should be using this occasion to raise different questions; serious, national questions. Questions we ponder but seldom openly entertain.

When should we go to war?

How should we decide?

How should we authorize, resource, and conduct it?

How do we know when it’s over?

How should we think about its risks?

This kind of exercise takes us back to our core national identity and the fundamental notions of war and peace that informed our nation’s founding.

Founding ideas about war and peace probably seemed complex to their authors in the late 18th Century, but have since been made more so by a wholesale revision of the context within which they are applied, and the emergence and refinement of a “law of war” … which attempts in its own nobly absurd way to marginally govern the ungovernable.

While we can’t wish away the two centuries of societal and global change that have introduced variance between what we set out to be and what we’ve become, we can embrace a citizen debate about the relationship between war and American society. As a nation, we’re trapped in a cycle of perpetual conflict, constantly ensnared in offshore violence that may or may not be debasing the national conscience, but is certainly carrying us further from our ideals. Founded on tranquillity, we’ve become warlike.

We’re also going broke from all of this. Or more precisely, our descendants are going broke before they’re born. And in the meantime, we’re spending less on domestic priorities Americans care about, mainly because our hard-earned revenues are invested in foreign activism. Though, to be fair, we are far from consensus on national priorities, as one recent poll indicates.

Why do we fall into the traps of war? Why does it seem our war decisions actually work against our interests? In the main, it’s because we make our war decisions the same way we make our other political decisions — incrementally, and using fractious processes that abandon principle and rationality for the sake of noisy compromise (or at least a theatrical version of it).

But this model doesn’t work well when it comes to war because although war is an extension of politics, it doesn’t behave like a normal political product. Once unleashed, it can no longer be actually or perceptually governed, compromised, tweaked, or regulated. It is a one-way door; once you go through there is no coming back … you must build a new exit. To undertake it means accepting that it will obey and reward those who understand it and will punish those who don’t.

Understanding it is largely about history. We can’t hope to prevail if we don’t understand what has allowed us to prevail or caused us to suffer in the past. We can’t minimize risks and costs if we don’t internalize the lessons our enemies have taught us in past wars. And that’s bad news for us. We’re an ahistorical, prospecting culture; we look forward and spare only a passing glance for what’s already happened … especially when looking at it would be inconvenient to our wishes for the future.

But we’ve most fundamentally lost our way in understanding the peculiar way in which war interacts with our political system (or should). Our founders installed heavy safeguards to prevent involvement in war in all but the most extreme circumstances of self-defense. They were openly against the use of violence to solve problems, and having studied history, they understood how the risks of war could be obscured by power, populism, and bloodlust. They envisioned their new country’s future as modest and cloistered rather than globally involved and powerful.

But that future was not to be, and as the world and our own choices have pulled us away from that modest vision, we’ve become more susceptible to the prospect of frequent or even endless war … the troubling notion that compelled our Constitution’s framers to put their hands on the scale in favor of restraint. As the country they founded has been drawn into a powerful role of global leadership, the temptation to develop far-reaching interests and secure them with armed force has overwhelmed political constraints designed to rarefy war. It has also centralized Federal power and concentrated it in the Executive Branch in a way that would have made the framers more than a little nervous.

With the march of time, war has morphed insidiously from an activity to be avoided at almost any cost to an activity with political and economic incentives often irresistible to an executive branch with more power than was ever intended and a relatively free hand to justify and prosecute war without a meaningful brake on its authority.

But even when war is justifiable and executed with initial clarity of purpose, it can drift into disaster if we’re not thinking iteratively and coherently about it. Given that political consensus for war is front-loaded and consensus to disengage from it is elusive, it is perpetually at risk of becoming perpetual.

That is, unless we steer it with a set of ideas around which we’ve gathered a governing philosophy. If we were given a clean slate and allowed to write our own theory of war, what would it look like? We’d have to quarrel about it a lot to get to anything like a consensus.

But quarrel we must. If we don’t revise our approach to war and peace, history provides little reassurance of a future. Endemic war is a reliable predictor of collapse, and the American predilection to avoid difficult discussion for the sake of theater, distraction, or comfort has arguably already set us on such a path.

How do we change course? I believe we start by contending internally with the meaning and operation of war in our society. I have my own propositions to start that conversation, but I will save them for later.

For now I will simply propose that war is the ultimate human paradox and the ultimate American problem. The only way to prevent being seized with it is to proactively obsess over it. The object of war is control, but war itself cannot be controlled. Pay it too much mind and it will drag you down … ignore it and it will ambush you. The fractured American psyche is at once drawn to it and terrified by it, a cycle we can only break by that ultimate form of talking therapy: democratic debate.

Written for Dale E. Carr, a hard-working husband, father, and American war veteran, 1948-2019.

TC is an American writer, manager, veteran, and strategist writing from his home in the U.K.

Amazing TC.