We think we know a story. But we don’t. We only know how it ends.

In 2006, I came close to killing myself.

I was piloting a C-17 on a low-level training mission in the Colorado mountains. We diverted from our planned route briefly to overfly a secluded lake. It was a wondrous few seconds.

But there’s a reason, aside from the timeless beauty of an untouched back country vista, why I’ll never forget it.

Wonder gave way to horror as we realized instead of the outlet route depicted on our chart at the far end of the lake, there was only a cliff with a shallow crevasse. We had walled ourselves into a box canyon.

With a lap full of control stick and throttles against the forward stop, I worked desperately to get us back the altitude so frivolously shed on a fool’s errand. But we were at the mercy of math. We’d either caught our mistake in time or we hadn’t.

Passing less than 50 feet from terrain in an aircraft with a 170-foot wingspan, we survived by margins as threadbare as they get. But it was enough. A change of underwear and many gray hairs later, I’m still here to tell the story.

Eight years after this incident, I came close to killing myself again.

This time around, the moment was less vivid. My heart rate didn’t so much as twitch. In fact, I didn’t even recognize it had happened.

I’d handled the equivalent of a nuclear bomb capable of vaporizing my life and ruining my family. Of altering the trajectory and dimming the prospects of everyone in my orbit.

And yet, I was clueless, wandering through life never knowing just how close I’d come to a much different and much darker journey.

That is, until now.

They say nothing creates clarity quite like having a loaded gun pointed at you. In 2006, I found this to be true.

In the weeks after the box canyon, long after the debrief which freed everyone to move on from it, I continued to ruminate.

I would, from time to time, spend a few hours in a self-built psychic jailhouse. Forcing myself to relive those few adrenalized ticks of a near-doomsday clock. It was my way of keeping myself open until everything I needed to learn was internalized.

It was on my planning checklist for every mission I flew for a long time. I was iteratively branding those lessons onto my brain by embedding them into habit patterns.

Don’t fly unplanned route changes without necessity. Don’t deviate cheaply from a well-made plan. Don’t fly low to the ground in unfamiliar terrain without a fresh risk analysis.

These things got spliced into my DNA.

Before I tell you why the aftermath in 2014 was different, let me tell you about a fella named Randy Ramseyer.

Summertime in our household is also known as football drought season.

Wandering in the relative desert of entertainment, we survive by scraping the built-up barnacles from our various streaming playlists.

This summer, the exercise led us to twin docudramas Dopesick and Painkiller, each taking its own stylistic and narrative angle through the same story, the epidemic of opioid addiction which has claimed more than half a million American lives.

It was in these stories, and in the subsequent fascination with Beth Macy’s writing and activism on the subject, that I encountered Ramseyer.

He’s one of the federal prosecutors who challenged big pharma in an effort to throttle the opioid crisis. We might call it a Herculean effort, but it managed only a milquetoast outcome. More than a 100 people continue to die every day from narcotic painkiller addiction despite Ramseyer and a legion of other unknown heroes pouring their lives into combating it.

Ramseyer is also a prostate cancer survivor. He was prescribed OxyContin to control his post-surgical pain, but opted for Tylenol. He’d been in the trenches fighting the epidemic for years by that point. He knew the danger.

In a poignant Dopesick scene, Ramseyer’s character crystallizes the opioid patient dilemma when he explains how being prescribed Oxycontin scared him more than his disease. In that moment, he calculated that cancer might kill him, but his medicine definitely would.

Think about that.

Here’a guy splayed half-lifeless on a gurney, hurting from head to toe. Sweat beads pool between the bulging lines on his forehead as physical anguish chisels his normally affable and soft-featured face into a haunting grimace.

A nurse warns him to be careful about gnashing his teeth.

He’s insecure about the future. Wracked with worry. Weak. Too hungry to sleep, too tired to drink. Never more vulnerable.

And in this moment, he is clear about what scares him most.

The medication prescribed by his doctor.

This the book definition of fucked up.

Both of these shows are eminently watchable, and they are important. But before I explain why I think so, let me tell you about a condition called gout.

Gout is an inflammatory problem of the extremities, usually the joints of the feet. It’s a type of arthritis. We associate it with old-timey monarchs and wealthy feudal landlords because the consistently rich diets and girthy waistlines of “the good life” are among its triggers. It’s more complicated, but not important.

What I really want to say about gout is that it hurts like hell.

The pain varies by the severity of a flare-up, but in pure form it’s unlivable.

Like someone boiling your foot in acid, causing it to swell until the skin is taut as a snare drum. Then relieving the pressure by stabbing it repeatedly with an ice pick, then using the red-hot glowing surface of a scalding coal to cauterize the wounds. Then cooling it off in an acid bath teeming with baby piranhas.

There is less comedy in that description than you think.

I asked AI for an overview of gout pain and here’s what it had to say.

Walking on a foot inflamed with gout is not possible. At least not without shrieking in a socially unacceptable manner. Just ask the people of Killarney, Ireland, all of whom heard me cursing my own birth and begging for a hacksaw as I limped the mile from the pub to my hotel a few years ago.

Putting a sock on such a foot is a non-starter, much less a shoe. And at the height of a gout attack, you can forget about sleep.

In 2014, for reasons I didn’t understand but do now, I suffered a gout attack in my right foot. The pain was unlike anything before or since.

It made me nauseous. Ill-tempered, like a caged dog getting poked with a stick. Basically non-functioning, unhappy, and compelled to do something I hardly ever did back then.

I went to a doctor.

And snarled with menace, through a clasped jaw, “WTF is wrong with my foot.”

The general practitioner wasn’t sure. But after spider bite, allergic reaction, and broken bone were disqualified, gout was the default verdict.

The doctors weren’t certain what had triggered it, whether it was a one-off or the first in a series, or how long it would take for the attack to fade.

What they did know how to do was assess and treat my pain. So they asked me a few questions and made some tactile and visual observations.

The doctor told me if it the attack didn’t clear in a week, to make a specialist appointment.

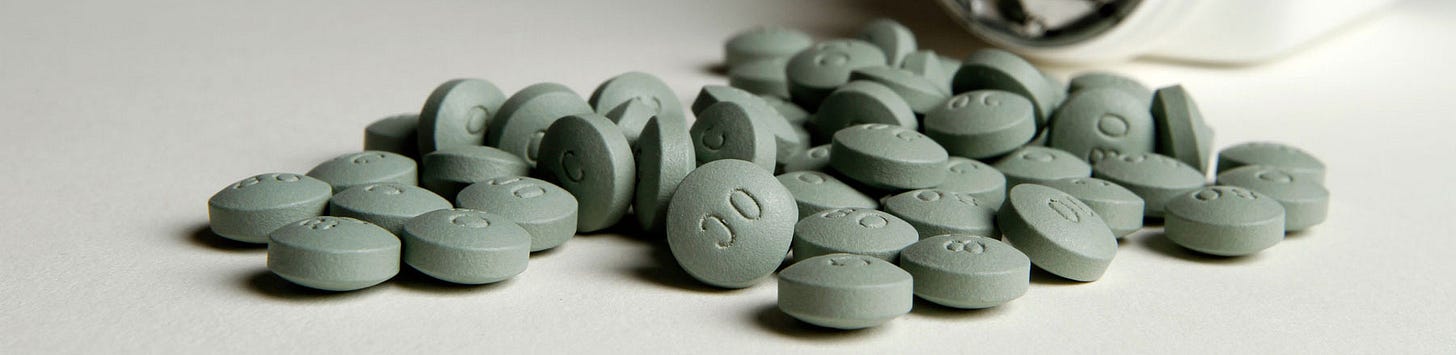

And then he handed me a prescription for 50 OxyContin pills.

“These will get your pain level down and help you sleep. If you need a higher dose, call the office and I’ll update your scrip.”

My wife and I had been relatively observant people. Aware of what was happening in the world around us. We watched the news. We had kids and kept ourselves informed and civic-minded, if for no other reason than to protect them.

At the time, I was a prosecutorial intern in the US Attorney’s Office in Boston. Not long before gout hunted me, I’d sat through a seminar about clinics in Massachusetts over-prescribing narcotics.

So I knew in some vague sense that these drugs were still a problem, even if I also knew OxyContin manufacturer Purdue Pharma had pleaded guilty years earlier to misleading the public.

Hailing from an Ohio town ravaged by painkillers and soon after by heroin, I probably had more than an average interest in the opioid epidemic. I knew the damage it was inflicting.

And yet, at least at first, I didn’t bat an eyelash when given the prescription.

I was in considerable pain. I trusted my doctor. He knew his business. And in my mind, there was this vague sense that the opioid crisis was something in the past. That accountability had been exacted, and changes had been made to the formulation of the drug to reduce addictive properties.

Actually, the only adjustment to Oxy production was to prevent it becoming a powder when crushed, so it couldn’t be snorted. But it was the same chemical it had always been.

Which meant that as my wife drove me home from the pharmacy, I wasn’t holding a bottle of pills in my hand so much as a 1-gram life grenade.

I didn’t clock that. Didn’t spot the issue. So when we got home, I took one.

What happened next is the reason I can write this story instead of having a different story told by others.

For 8 hours after taking a single 20mg OxyContin tablet, I didn’t feel my pain anymore. In fact, I didn’t feel much of anything. I didn’t care about anything. I wasn’t worried about anything. I was basically levitating.

I was able to walk just fine. No shrieking, limping, or gnashing of the teeth.

And it was fantastic.

And I understood instantly why people in pain sought out this drug.

And it scared the living piss out of me.

Having seen the impact of drug abuse in my family as a youngster, I had a chip on my shoulder about it. I judged. I furrowed my brow. I disapproved and quietly shamed. I kept my distance.

My attitude today is different. I’ve softened. I’ve come to recognize our attitudes about drug use and addiction have been socialized and in same cases propagandized into us.

I’ve thought about how addiction happens, and become more tolerant toward those who fall into it. Because that’s what it is: something you fall into, not realizing the magnitude of it until you’re immersed and drowning in its consequences.

But in that moment, the stonewall attitude carried from youth did me a favor. Because as the effect of that Oxy pill wore off, I didn’t reach for another one.

With instincts triggered by the fear of how that first pill had felt, and honed to a sharp edge by years of rejecting the culture of drug abuse, I calmly collected the bottle of pills and made my way down the stairs, gingerly hobbling on the inflamed foot no longer swaddled by narcotics.

I took off the cap, upended the bottle, and poured the contents into the toilet.

Then flushed.

And then politely asked my wife to hit the Star Market and get me some Ibuprofen.

At the time, it didn’t feel well-reasoned. I wasn’t consciously swerving a disaster. The amygdala was in charge. Even if logic could have subdued fear, I didn’t give it a chance.

I just reacted.

I could just as easily have talked myself out of it, because I wasn’t attuned to the severity of what I was playing with. But I didn’t. I acted decisively, and nothing intervened to pause events, which would have given me time to hesitate and think.

I was lucky.

To look at it any other way would be dishonest.

Many others were not lucky. They didn’t feel fear, or reacted to it logically rather than intuitively.

Wracked with pain, they did what their doctors told them to do. And they felt better, at least at first.

And then the pain came back, so they upped the dosage under doctor’s orders. And that worked. And so it went. Until one day, they had forgotten about the pain altogether, but couldn’t stop thinking about the medication.

They needed it to function. And needed more. And when they couldn’t get it, withdrawal hit them like a physical and mental wrecking ball. They couldn’t think. They couldn’t sleep. They couldn’t work. Breathing itself felt like a tall order.

They were addicted.

Not because of street dealers, cartels, or criminal gangs. And not because of their own weakness or criminality.

They got addicted not by breaking doctor’s orders, but by following them. OxyContin addicted people when used as directed.

Doctors were unwittingly made into street dealers by the real drug lords and their facilitators.

They prescribed OxyContin because the FDA had certified it wasn’t an addiction risk when used properly. And the FDA did this because it had been misled by executives, or had been furnished enough cover for an approval decision and then co-opted into granting it.

The FDA was at that time chronically understaffed, under-funded, dysfunctional, captured by industry, endemically corrupt, and lethally inept. Most of which remains true today.

Once the hook was set, addicts sought and secured their drugs however necessary. They spent life savings. Sold their houses. Bankrupted and alienated their families.

Once homeless, they slept in their cars. Then eventually sold them, choosing to stay medicated rather than have a roof over their heads.

They stole from, robbed, and harmed others. Many prostituted themselves.

They were dehumanized, navigating the horrors of addiction and pressures of rehabilitation alone after destroying every relationship they had. They sold their souls to the devil only to find him a cold companion.

And along the way, many turned to substitutes when Oxy could no longer be had. Heroin was a popular proxy. Untold thousands died of overdoses in filthy drug houses, needles still astride their veins.

Months before, they’d been normal. Upstanding. Lovable. Affectionate. God-fearing and law-abiding. In many cases sweet, modest, educated, capable, and important to others. Loved. Cherished.

And none of that mattered once they were in the grip of addiction.

And it all started because they went to the doctor and followed that doctor’s instructions. In doing so, they trusted not only the doctor, but the entire system of regulations and safeguards designed to protect them. Safeguards paid for with their taxes.

These 500,000 pain-sufferers were not marginal dregs roaming the fringes of society. They were ordinary, everyday people. Professionals in many cases — people whose shame was compounded by the idea that they should have known better.

Many addicts were themselves doctors, nurses, and pharmacists. Others were police officers, detectives, and lawyers.

One lesson of the opioid epidemic is that you could find yourself in the clutches of addiction through no fault of your own. And the more responsible and drug-free your prior existence, the more confusing and confounding the predicament of being addicted without having taking a culpable action to get there.

Addition is not a character flaw. Addiction changes brain chemistry.

“Willing your way through” doesn’t work. “Try harder” doesn’t work. The choice to take a drug or flush it exists in a brief and fleeting moment. Once the brain begins to change in response to the drug, choice doesn’t work the same way.

Professional care and intensive therapy are usually required for recovery after that point. Even after drug abuse stops, the brain can take years to heal. And in that time, the addict is one fragile moment away from undoing everything.

In the pain of recovery, hounded by the shame of what they did to sustain their addictions, many decide they'd be better off feeling nothing at all.

Addiction claims lives even among the sober.

This is not a call for activism or reform. Though we could all be forgiven for expecting such things.

Instead, my modest goal is to provide the three lessons now clear in my mind after revisiting my near-miss with OxyContin in light of what I now understand.

First, sometimes the cure is worse than the disease.

Dope pushers, be they legally sanctioned or otherwise, cloak themselves in the benevolent garb of pain relief.

But pain is part of life. It’s as much a part of life as breathing.

Trying to remove pain from life is an affront to nature. Experience tells us that avoiding one sort of pain only leads to more of another sort. It will bubble out of us no matter what, because pain is an inexorable force of nature as elemental as oxygen.

This is not to say all pain is constructive.

There is such a thing as unnecessary pain. Pain which serves no purpose and is therefore cruel and excessive. The humanist impulse to eliminate needless pain is powerful and valid.

The power of that premise is what big pharma leveraged to make their money. Erasing the distinction between necessary and unnecessary pain, they pursued a vision of removing all pain.

And there’s a reason they took that approach.

The world is full of pain. If your drug treats it, and removing it is always good, then you have an unlimited market.

But we need it. Pain teaches us, and by learning we avoid more pain.

There are those among us who desperately need help controlling pain that isn’t helping them. We can easily imagine and maybe even know people in this situation. Including many whose pain is permanent, meaning that without help to contain it, they have no life at all.

But pain also gives definition to pleasure. Without pain, pleasure loses its feeling, and in the restless search to find it again, we find only different flavors of pain.

Second, sometimes the cure is worse than the disease.

I grew up in an environment socially and ideologically opposed to bureaucracy. My adult journey has only served to intensify skepticism about overgrown organizations.

I’m literally writing a book about how big organizations develop pathologies that make their people miserable. Obesity isn’t just an individual human problem. It’s a metaphor for problematic companies, nonprofits, military services, and government agencies.

But sometimes, in our haste to debilitate bureaucracies, we can harm the part of an agency that was actually functioning and important.

The FDA’s failure to properly regulate OxyContin is a national scandal and should be the subject of a national review. Even more damaging is the FDA’s hesitancy to correct itself once the bloody and lethal evidence of its error became obvious.

The FDA has been chronically underfunded and perennially assailed by a powerful drug lobby. In a quarter century, it has never gotten the budget requested, which was already way lower than it actually needed. The agency has openly told us for decades that it cannot effectively regulate. Pleas met with further cuts.

It’s one thing to say we’re not gonna be huge on regulation because we understand how that chills markets and reduces the solutions available to the public.

It’s another to say we’re going to limit what we spend on assuring the safety of our food and drug supply to less than 1% of what we commit to military budgets.

Our cure for bureaucracy is allowing greedy nihilists direct access to consumers who understandably but wrongly trust in the safety of the drugs they’re being sold.

That cure is worse than tolerating the ills of an overgrown FDA.

Third, sometimes the cure is worse than the disease.

The judgment and shame we wield serve a social purpose. Collective disapproval for a thing reduces its incidence. While we could do without some of the forms stigma takes, we can’t deny that the impact of it has often been positive.

But our attitudes toward drug abuse have not changed even as the pathways of abuse have fundamentally shifted.

We now find ourselves in a situation where addicts without culpability for their addictions are marginalized and shamed, compounding the psychological challenge of recovery. And they are ostracized and often imprisoned for the actions they took to sustain their addictions, having crossed the line into culpability when they were not of sound mind. Not making good decisions.

Our judgments seek to cure a social ill. But by acting as an obstacle to recovery, they make things worse. An addict who sees no real chance of redemption has no incentive to stay clean. Stigma in this context prevents recovery and sustains demand for the illicit drugs addicts turn to when their legal access runs its course.

There are those of us whose lives were directly touched by the OxyContin cataclysm. And the rest of us are the lucky ones.

I’m in that lucky category. I came within inches of slipping over that line separating sanity from madness. There but for the grace.

Being honest about it is the path to knowledge.

In 2006, it was obvious I needed to learn. In 2014, it wasn’t. But it is now, and circling back to that unmarked, unconscious crossroads has taught me a lot about human frailty.

And a lot about my own judgments. The shape of my mind and heart have changed by empathizing with those who, for whatever reason, didn’t flush away their bottle of pills.

As a country and as communities, we have to be honest about the opioid epidemic, how it happened, and why it has killed so many people and destroyed so many families. If we don’t understand that in at least the same detail we understand reality TV, we’re too far adrift to deserve saving.

And if we don’t learn, we will suffer again. That’s the nature of pain.

We think we know a story. But we don’t. We only know how it ends.

That ending marks the final waypoint in a long journey that starts with good people, animated by positive intent, falling into traps we set for ourselves without even knowing it.

It’s in our power to know the whole story. I think we ought to try.

Tony is an American writer.

TC…powerful and illuminating piece. Thanks for sharing.