Organizations often adopt policies that seem sensible in principle, but become self-defeating when activated in the real world.

The first time this happens, it’s reasonable to call it misguided.

But after it’s understood and yet continues to happen, we must give it the appropriate label: dumb.

I never stop being fascinated by the capacity of large organizations to adopt dumb ideas.

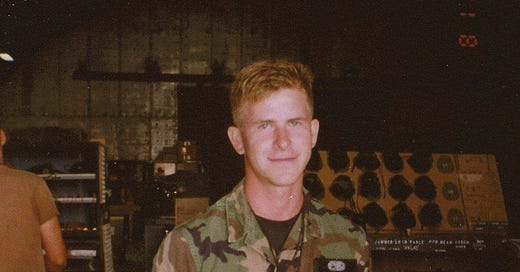

In August of 1994, I made Staff Sergeant in the US Air Force. Me getting promoted isn’t the dumb idea I want to pull apart. Though it might be argued it was, also, dumb.

SSgt was my first opportunity to earn a promotion. It felt powerful to shape my own future.

Back then, promotion was a matter of (a) points from time served in your current grade, (b) points from performance as compared to peers, and (c) points from promotion testing.

(a) could not be influenced or controlled.

(b) could be influenced but not controlled.

(c) was almost completely in the individual’s control.

I was low-tenure but had performed well.

I focused on what I could control and studied for a solid year. That year of focus reflected my ambition for more responsibility, which some of my peers did not yet have.

When the results came, I had scored high enough to overcome my low tenure. I was totally jazzed. I bought my cat some gold-label Fancy Feast.

No one had to push me to pursue that promotion. I wanted those stripes and the additional work and duty they would mean. The system was simple and clear, placing my destiny in my own hands.

The promotion rate that cycle was just under 18%. And still some idiots made it through. I am living proof of that.

Now, imagine a world where 40% of candidates are promoted. Think how many more idiots will advance in a system like that.

That’s the world I found myself in 17 years later as a squadron commander. And as concerned as I was about some of the wrong people getting promoted with such a low bar, it was all made worse by a guy named Terry.

Terry was the senior enlisted advisor for our organization. Kind of a Grand Poobah for the enlisted ranks whose role was ostensibly to safeguard their interests, though I rarely witnessed him do so.

One day, in a staff meeting with my fellow commanders, I received a sermon from Terry about how our promotion rates to SSgt were too low. Apparently, other units were getting slightly more people promoted, and this was earning Terry some unwanted attention from his eight bosses.

To burnish his street cred, he needed to get that metric into the green, even if it meant someone incapable of generating steam on a mirror became a USAF NCO.

I supposed the premise was fair. When your people are comparatively slower to progress, it raises fair questions about whether you’re setting them up for success.

The correct response to such healthy pressure is to, you know, set them up for success.

Give them a sustainable workload.

Give them resources so they can perform at their best.

Give them solid leadership.

Inspire them so they want to perform well and progress.

Tend to their physical and mental wellbeing.

Make sure they have time to study. Time is the most valuable thing you can give your people.

Terry’s response was to insist people who lacked ambition be “pushed” to study harder. Be required to attend study skills sessions. Be required to attend “development” sessions explaining and helping them better game the promotion process. Be required to absorb counseling from an anointed Grand Poobah on their previous test results and how to improve.

Now imagine a legion of Terrys Terrying incessantly in a scaled organization, with tens of thousands of promotion eligible airmen being led like horses to water.

Some of them chose to drink, resulting in marginally improved promotion rates. Which made various Terrys look slightly better on an obscure scorecard.

But it also resulted in an even higher-than-reasonable rate of idiots getting promoted.

This all had a deleterious impact in the quality of the NCO corps, and was totally uncool for airmen subjected to shaky supervision in the years to come.

The USAF now has enlisted retention and recruitment problems. It has suffered from years of noticeable deterioration in its overall discipline and morale. It is a brand in decline.

I don’t know anyone who believes there isn’t a connection between these current maladies and the antics of Terrys past.

Aliens watching from space would draw the conclusion that when half your people are progressing to the supervisory level, it’s not selective enough.

If someone lacks the ambition for more responsibility, they should not be coerced or pushed or cajoled or hectored into progressing.

Best case, you annoy them into distraction and their performance suffers.

Worst case, they actually listen to you and seek progression they don’t want. Which by definition means they are unsuitable.

Even worse case, they succeed in gaining a role for which they have no ambition.

If there is a broad lack of ambition for promotion, the answer is to make promotion an attractive enough proposition that strong performers want it and compete actively for scarce opportunity. Not to push people into wanting it so some Terry can say they made their numbers.

I wish this was just a vignette about USAF NCO promotions, but this pathology exists pretty much everywhere.

For example, some military pilots want to become commanding officers, and are willing to undergo the education, development, and leadership tests required to earn that privilege. Even if it interrupts or dilutes their experience of flying airplanes.

Other military pilots want to fly their whole careers. They love exercising a particular set of skills and a certain level of solemn responsibility, but they don’t desire promotion, fame, politics, or bureaucracy.

The USAF has always, to its own grave disadvantage, insisted on fighting this distinction instead of embracing it. It has always countenanced sideline-dwelling Terrys castigating combat-seasoned operators who aspire to simply continue killing enemies rather than become professional managers.

This has always been a brake on morale. It’s gotten much worse in recent years as the Terrys have gained the upper hand, enforcing a policy called “up or out.”

An up or out promotion system means everyone must be ambitious or eventually lose their job. And since promotion requires seasoning outside the cockpit, the Air Force systematically plucks pilots from their flying roles to send them to schools, staffs, and other non-flying roles so they can preserve the opportunity to advance.

This is one of many policies that has turned people away from one of the coolest jobs in the world, resulting in a pilot shortage of about 2,000 which has persisted for years as an undeclared national emergency.

Think about that. The best air service in the world can’t retain enough pilots to fly all of its aircraft. And part of the reason is that it refuses to let them fly, insisting instead that they Terry their way through a flying career, pretending to care about management so they can avoid getting culled.

Little wonder thousands of them end up at the airlines instead of continuing to serve. And for every one who decides to emigrate to private enterprise, the USAF pisses away millions of dollars in taxpayer-funded training.

I saw the same foolishness in Amazon talent assessments, where we routinely discussed “time in current role” so pejoratives could be applied to those managers not in enough of a hurry to climb the ladder. Sit in role too long and you’d get managed out of the business.

Up or out is one of the dumbest ideas ever, right up there with ketchup and mustard in the same bottle. It is motivated by the principle that stagnation is bad for teams, but persists because it also serves as a handy tool for manicuring staffing when the need arises.

And because through the arrangement of pathological incentives, it has gained a bureaucratic constituency. A legion of Terrys to push it along. And these Terrys are by no means passive, but evangelists who spread their spores into every molecule of the organization’s atmosphere, until the mold of careerism populates every surface.

But …

If an operations manager doesn’t want to become a VP but they are doing well at current level, leave them be. They are adding value.

If a pilot doesn’t want to be a commander or a general, just let them fly. Their expertise could be critical when combat comes again.

If an airman wants to turn wrenches for a few more years before taking on supervisory responsibility, don’t rush them. Their depth of skill often makes a huge difference.

Organizations need a cohort who are superb at their jobs and undistracted by the requirements of ambition.

Up or out routinely exceeds the reach of principle and becomes a way to isolate people who are not mega hungry all the time. But if everyone is mega hungry, who is just getting their head down and doing the job?

The result, most often, is a lot of irritated people and organizations which have diluted their own readiness. Which they then blame on other stuff.

One of the marks of a great organization is its protection and celebration of those who create its value.

When you see an organization harassing this group of people, even under the banner of well-intentioned policies, you’re watching decline before your very eyes. Because greatness will not emerge from the mass rationalization of dumb ideas.

And the poster child for such decline will be a passionate bureaucrat pretending to care about others but really just trying to clean his own name and feather his own nest. A mindless minion reacting to pressure from his boss rather than doing what makes sense.

In other words, a Terry.

With apologies to all the good people out there who happened to be called Terry.

TC is an American military veteran and organizational behavior expert passionate about elevating the leadership conversation. This piece touches on themes featuring in his upcoming book “Tailspin: How an Authority Culture Broke America’s Air Force.”

Using rank as a proxy for pay and privileges drives this pathology.

After a decade working with Air Force Reserve, I found they have a superior model. Those who want to be fly, turn wrenches or be super technicians can spend their entire career doing so. Promotion opportunities are presented but the individual must seek them out. As a citizen Airman they can choose to be full time or a weekend warrior. It is a place where individuals can thrive.

My son joined the Reserve directly for ROTC. He sees the same advantages I saw. He’s thriving in the environment.

IMO more if not the majority of the Air Force Mission should move to the Reserve. It will improve morale, retention and the mission.