The Hope That Kills

The hollow gesture ... a "gift" that keeps screwing everyone the whole year 'round

If you are an employer, an employee, a prospective employer or employee, a former employer or employee, a fan of pre-millenium Christmas classics, or just someone fascinated by condiments, chocolates, pizza, or empty gestures, this post is for you.

Which should just about cover the whole of civilization.

In the movie National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, the fictitious Clark Griswold understandably loses control of his emotions on Christmas Eve. Tearing into the long-awaited telegram containing his bonus, he’s expecting a check big enough to fund an in-ground pool.

His expectation was reasonable. In the past year, he has unilaterally engineered a semi-permeable, non-osmotic, non-nutritive, crunch-enhancing cereal varnish which promises to boost his company’s revenues. In the quaint universe of Christmas Vacation, we’re meant to believe Griswold still believes there’s a link between the value added by an employee and the end-of-year remunerative gesture made by the employer.

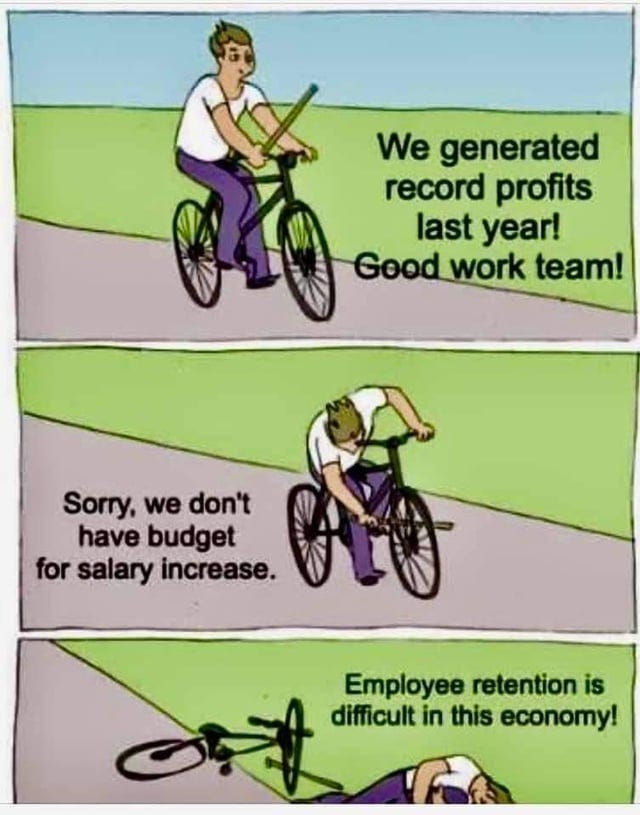

But we and Clark come to find out we’re in a world of declining horizons. In such a world, individuals work just as hard as they always have (or harder), create as much value for their employer as they always have (or more), and receive less in return.

Griswold receives not a bonus, but a subscription to a monthly condiment club. Only after his supervisor is kidnapped, beaten, falsely imprisoned, exposed to a supermajority of the torts available in civil litigation, and publicly told he is too greedy by his fur-sporting wife does this wayward, jelly-flogging grinch relent.

He restores Clark’s bonus.

Of course, in doing so, he gives Griswold an inflated sense of hope, that despairing hobgoblin of false expectations.

But the core proposition of the plot comes moments before, when Griswold holds his Jelly of the Month certificate in his trembling hands, stupefied. As his dream is pulled from orbit, Griswold boils over with rage, bombarding his line manager’s good name with a payload of creative aspersions, which we can economize here as “bug-eyed, spiny-lipped, snake-licking, dirt-eating, inbred sack of monkey shit,” before chugging booze and pleading for Tylenol.

Griswold is a man over the edge.

Now some advice. If you’re an employer, go back and watch Griswold melt down again, but this time imagine he’s one of your employees.

I promise this is how your people feel at the end of the year when they have done enough to reasonably expect a genuine gesture, and instead you make a hollow one.

Too many companies fall into the trap of believing their people are too dumb, too unassuming, or too aloof to be offended when a year’s worth of value injected into the bottom line is recognized with an immaterial half-measure, often delivered with a phony smile.

Don’t be Frank Shirley. Be honest with yourself and with your people.

As the end of the year approaches, has your business unit beaten financial projections? If so, do you attribute this to the ingenuity, commitment, and discretionary effort (at personal sacrifice) of your team, or at least certain among them?

If the answer is yes to both, give them money.

Yes, money.

Not free donuts in the office introduced with a 30-second monologue pried from the pages of an airport bookstore self-help manual.

Not a t-shirt to commemorate the work they did.

Not a water bottle or a keychain or a lanyard.

Not a ticket for a raffle. You didn’t profit by chance, but on purpose. Their purpose.

Not a donation to The Human Fund.

Not an occasional handful of chocolate candies delivered with a threadbare verbal offering of thanks (yes, Amazon, that one’s for you).

And please, for the love of God, not another pizza party, which fails on both substance and originality.

Look, I get it. Companies exist to make money. When they succeed, it should enrich those whose capital at risk enabled their growth.

But this principle doesn’t stretch to infinity. Or maybe I’m saying I hope it doesn’t, or wish it didn’t.

Companies that behave with a sense of fairness and justice earn the respect of their employees. Companies that properly recognize those who create value enjoy comparatively higher job satisfaction and retention. Discretionary effort goes up along with innovation. Costs of turnover come down. The bottom line swells.

When people feel accurately recognized, expectations stabilize and they begin to trust. With trust and the sense of belonging that soon follows, you have the promise of a positive work experience, which is something employers should create and safeguard.

And the inverse of everything in the preceding two paragraphs is also true.

But I have one more volley for those who say “but that extra profit goes to those who invest in us.”

Your employees invest in you too.

It sounds obvious. But actions in the real world suggest it’s not well understood.

Whether they hold shares in your company or not, your people are probably your biggest investor base. You get their vitality, their energy, their focus, their commitment.

You get most of their awake life. More than their families get when we count the time we typically count. Even more when we count the time off-clock when they are thinking of work, preoccupied with work, and doing work, usually in defiance of what’s best for their health and relationships, but in support of what’s best for the team and business.

If you want your people to feel about you the way Clark Griswold felt about Frank Shirley, shower them with penny chocolates or a slice of Aunt Bethany’s jello mold.

Sure, it is “a cheap, lousy way to save a buck,” but it’s a move, and you won’t be alone making it.

But if you care, or at least want to unleash the productivity and loyalty of credible appearing to care, give them a slice of the commercial value they created. This is what every study, abetted by common sense, tells us they want.

If you can’t or won’t provide monetary recognition for money-generating deeds, cross your arms and do nothing. And accept whatever follows. Don’t fake caring in a way that is obvious and insulting.

You will at least spare the insult too often added to injury.

Thanks for reading my newsletter. It is free to subscribe. Please feel free to do so, and to invite your friends.

TC is a former senior leader in both commercial and military operations who writes and speaks on leadership. He is an expert in organizational leadership and the creation and development of high-performing teams.

Fresh off the receiving end of such described "gestures", this hit home.