A few days ago marked the invasion of Iraq, which 21 years ago damned US military forces, their adversaries, and everyone caught in the crossfire to successive waves of senseless exertion, abyssal loss, and numb exhaustion.

And Iraq didn’t happen to us. We happened to Iraq.

Whatever happened there, however deep our scars, Iraq was pain we chose.

Later this month, we will honor the veterans of Vietnam, that bloody monument of generational suffering whose impact was supposed to warn us away from avoidable conflict once and for all.

Vietnam was pain we chose.

And in this moment, having only just crawled free of a three-decade quagmire, we sense the tightening of tentacles encircling our wallets if not our very limbs, reaching from distant cataclysms in Gaza and Ukraine.

Absent clear purpose, we risk defaulting into pain. And to default by collective indecision and ambivalence is itself a choice.

If we look back in a decade and find ourselves bloodied and broken yet again, it will have been our choice.

It’s a moment for looking in the mirror.

In doing so, we hazard a reflection of terrifying futility. A series of grim admissions about our own nature, the inevitability of violence, and the compounding gravity of competitive mayhem once unleashed.

And yet, we need that mirror.

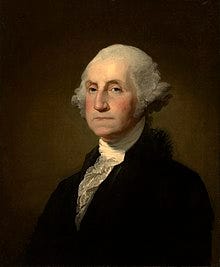

Without facing up to the primacy we’ve allowed war to occupy in our national life, we risk running further afoul of the worried wisdom George Washington gave us in his farewell address.

Political factionalism, over-reliance on changeable alliances, and the merciless grip of conflict once undertaken … these timeless pitfalls of failed societies troubled Washington’s realist mind.

So too should they trouble us now. Because we are now, and have been for a while, in so far over our heads that it’s hard to see our way out of a world gone mad. As leaders of that world, we can only look to ourselves to understand its madness.

We can no longer, if ever we could, pretend war is something which keeps happening to us.

It is pain we choose. We can stop choosing it, but I wonder if ever we will.

Quoting Viktor Frankl, an Austrian survivor of the Holocaust who went on to found an entire school of psychotherapy based on the search for life’s meaning, Vietnam veteran Max Cleland said:

“To live is to suffer, and to survive is to find meaning in something. For those of us who suffered because of Vietnam, that’s been our quest ever since.”

Cleland contributed these words to Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s excellent documentary The Vietnam War back in 2017, about four years before he died.

A politician active on matters of war and peace and an ardent supporter of the veteran cause famous for the phrase “war is not over when the shooting stops,” Cleland represented a generation of veterans whose voice is fading from the American conversation.

Today’s youngest living Vietnam veterans are in their 70s, and by now they’ve watched their country repeat the mistakes they bled to illustrate.

It’s at this point I will digress into personal reflection, which will crystallize why this time of year gets my wheels turning about this subject.

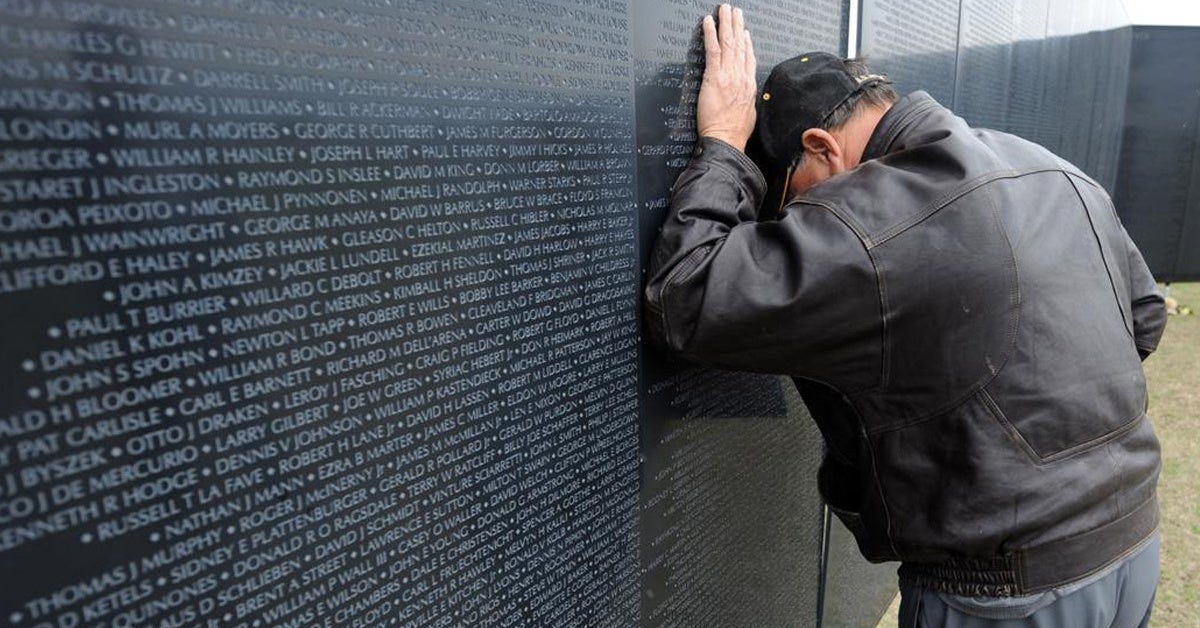

The picture below is my Dad, the late Sgt. Dale Carr of Marion, Ohio.

He was drafted into Vietnam straight out of high school and deployed in 1968. Deeply opposed to war and violence in general, he nonetheless answered the call of duty.

He fought in Pleiku, carried an M-60 for his squad, and came home half-dead with malaria, his spirit broken from watching his best friend die in combat.

That’s about all I know, because he seldom spoke about the war, even in the ripeness of time as we stood on common ground as fellow veterans.

When the subject was breached, the room went cold. A wicked wave of turmoil visibly washed over a man who exerted massive energy to bury his feelings about his time over there.

Dad died in 2019. The demons who climbed aboard his shoulders in Vietnam followed him into his grave. The wounds he suffered there chased him into it prematurely.

His mood, his temperament, and his worldview were shaped if not wholly defined by the short time he spent in Vietnam during his formative years. This speaks to the depth of the trauma he experienced there. Something representative of the millions of young Americans called into action.

While the war took half a century to drag my father down, it was swiftly merciless with many others. 58,300 Americans gave their lives, falling in the shadow of the estimated 3 million Vietnamese soldiers, insurgents, and civilians killed on both sides of the divided nation.

This death toll doesn’t begin to touch the actual damage in despair, disruption, instability, and massive upheaval triggered by this generation-spanning bloodbath.

The war has been collectively felt as a national wound, and later, a national scar. It has echoed across generations as a sorrowful warning: avoid war at all costs, because once unleashed, it brings Hell to Earth.

America’s involvement in Vietnam was a costly misadventure.

It began as an earnest attempt to confront and harass the spread of a threatening ideology.

It continued on the steam of outright lies from generals and politicians falsely portraying it as a worthy and successful cause because it was in their interest to do so.

And it was guided to catastrophe on the rails of absurd divergence between goals and resources, between rhetoric and reality, between principles and actions.

As the war unraveled, so too did the American conscience, and so too its sense of unity and collective greatness.

After thirty years of scarring and a seeming embrace of Vietnam’s lessons, America felt different; as though the wisdom of the war had made its mark.

Enmity for the soldier was replaced by respect. Generals advocated war policies which recognized the limits of military force and demanded exit strategies before considering its use. Veterans of the Vietnam experience populated senior posts in government and diplomacy, forming a vanguard of cautious sobriety.

And then, in the space of one terrible day in 2001, this entire body of lessons was shoved off the table.

Turns out they weren’t written in blood or carved into stone. They were scrawled on an etch-a-sketch which got shaken clean the instant we perceived the fresh spread of a threatening ideology.

And so the cycle began anew. Not one but two costly misadventures.

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began as attempts to confront and harass the spread of a threatening ideology (an earnest attempt in the former, specious in the latter).

They continued on the steam of outright lies from generals and politicians falsely portraying each war as a worthy and successful cause because it was in their interest to do so.

And they were guided into catastrophe on the rails of absurd divergence between goals and resources, between rhetoric and reality, between principles and actions.

This time around, there was no broad sense of national shame. No unraveling.

These wars were lived by a tiny sliver of the population and fought by volunteers. Americans weren’t taxed for them. Americans didn’t even vote for them in any meaningful sense given that both major political parties endorsed the conflicts.

While it’s great that soldiers haven’t been spit upon or cursed at the airports and Americans aren’t biting at each others’ necks (over this issue anyway), it’s alarming that twenty years of war at a cost of 900,000 human lives and $8T have not managed to stir anything close a national debate.

And now, in what passes as peacetime, we tender a historically massive defense budget, all by itself bigger than the GDPs of several major nations, which yet manages to under-deliver.

Chronic manpower shortages, housing costs not covered by paychecks, and a suicide epidemic kicked into the tall weeds by cynical bureaucrats are among the treats we get for 20% of every tax dollar we pay.

What those taxes should afford us is at least a conversation.

But that will only happen if we start asking questions and stop defaulting into painful choices.

When should we go to war?

How should we decide?

How should we authorize, resource, and conduct it?

How do we know when it’s over?

How should we think about its risks?

We might think these questions are answered by our Constitution or by legislation such as the War Powers Resolution. Or by our National Defense Strategy, which purports to make intent actionable within legal and budgetary constraints.

But the truth is we’re in default mode.

Administrations make defense choices and act upon them. Congress pays for those choices, offering little meaningful resistance or oversight.

Each time this happens, an additional degree of unchecked war power accrues to the Executive Branch.

Wars are no longer declared. They are “authorized” by Congress, which is just a way of providing money for what Presidents have already decided to do.

Without a process to declare war, we bypass a national debate about its costs and consequences. We later express shock and dismay at what it’s cost us.

But given we elect legislators too distracted by perpetual election cycles, fundraising, and rage-farming to properly represent our interests, we are getting exactly what we should expect. We are choosing this.

Founding ideas about war and peace probably seemed complex to their authors in the late 18th Century. They have been made more so by a wholesale revision of the context within which they are applied.

While we can’t wish away the two centuries of societal and global change that have introduced variance between what we set out to be and what we’ve become, we can embrace a citizen debate about the relationship between war and American society.

As a nation, we’ve trapped ourselves in a cycle of perpetual conflict, constantly ensnared in offshore violence that may or may not be debasing the national conscience, but is certainly carrying us further from our ideals. Founded on tranquility, we’ve become warlike.

We’re also going broke from all of this.

Or more precisely, our descendants are going broke before they’re born. And in the meantime, we’re spending less on domestic priorities Americans care about, mainly because our hard-earned revenues are invested in foreign activism.

We make our war decisions the same way we make our other political decisions — incrementally, and using fractious processes that abandon principle and rationality for the sake of noisy compromise (or at least a theatrical version of it).

But this model doesn’t work well when it comes to war because although it is an extension of politics, it doesn’t behave like a normal political product. Once unleashed, it can no longer be actually or perceptually governed, compromised, tweaked, or regulated.

War is the ultimate one-way door; once you go through there is no coming back. You must build a new exit.

Seeming to understand this, our founders installed heavy safeguards to prevent involvement in war in all but the most extreme circumstances of self-defense.

They were openly against the use of violence to solve problems, and having studied history, they understood how the risks of war could be obscured by power, populism, and blood lust. They envisioned their new country’s future as modest and cloistered rather than globally involved and powerful.

But that future was not to be, and as the world and our own choices have pulled us away from that modest vision, we’ve become more susceptible to the prospect of frequent or even endless war.

We’ve become a leading nation. And with global leadership comes the temptation to develop far-reaching interests and secure them with armed force.

This has overwhelmed political constraints designed to the contrary. It has also centralized Federal power and concentrated it in the Executive Branch in a way that would have made the framers more than a little nervous.

With the march of time, war has morphed insidiously from an activity to be avoided at almost any cost to an activity with political and economic incentives often irresistible to an executive branch with more power than was ever intended and a relatively free hand to justify and prosecute war without a meaningful brake on its authority.

But even when war is justifiable and executed with initial clarity of purpose, it can drift into disaster if we’re not thinking coherently about it.

Given that political consensus for war is front-loaded and consensus to disengage from it is elusive, it is perpetually at risk of becoming perpetual.

How do we change course?

I believe we start by contending internally with the meaning and operation of war in our society. I have my own propositions to start that conversation, but I will save them for later.

For now I will simply propose that war is the ultimate human paradox and the ultimate American problem.

The only way to prevent being seized with it is to proactively obsess over it.

The object of war is control, but war itself cannot be controlled.

Pay it too much mind and it will drag you down. Ignore it, and it will ambush you.

The fractured American psyche is at once drawn to it and terrified by it, a cycle we can only break by regaining situational awareness, asking questions, and following the answers where they lead.

Until we do that, we risk continuing to default into painful choices that defy our interests and defile our consciences.

If that continues to happen, we will have no one to blame but ourselves.

War, at this moment in time, is not something inflicted upon us.

It is a pain we choose.

Written for Dale E. Carr, a hard-working husband, father, and American war veteran, 1948-2019.

TC is an American veteran writing from his home in the UK.

Beautifully written. Thank you for sharing.