Companies surrender to a number of illnesses as they grow in age and scale, transitioning from a founder’s mentality to a corporate mentality.

One such malady the recourse to propaganda.

By this I don’t mean political messaging. Nor do I mean external advertising.

By this I mean internal communications designed to influence and persuade a company’s own employees.

For example, persuasive messaging on pay and benefits, which is designed to reassure or pacify employees questioning their wages.

Or issue-based messaging designed to bolster sentiment on safety, development, or diversity, for example.

But the species of propaganda on my radar today is when a company trots out its senior leaders like show ponies. The goal is to reassure employees they are well led by elite professionals. For a variety of reasons, this doesn’t usually work too well.

Which brings me to what I call the propaganda paradox.

It describes a situation where messaging seeking to create confidence in leadership actually has the opposite effect. Confidence is eroded by the messaging, which leads to the need for more messaging, which instigates the cycle again. And so on.

People hate being propagandized. It makes them reject the message even harder.

Propaganda was something I commonly noticed during my time in military service. Towering, vertical, hidebound bureaucracies do what is in their interest, including shoring up internal opinion to avoid friction in the ranks.

The Air Force ran notorious propaganda campaigns in the middle of the last decade as it sought to rescue declining trust and morale across the force. Each one of these deepened the divide between its leaders and airmen in the field. The result was morale so low that the service refused to publish the results of its own sentiment survey. This is where propaganda bombardment leads.

A couple years ago, I noticed Amazon engaging in this tactic during its 2022 “Ops Live” conference, essentially a big meeting in Nashville for its senior operations leaders.

My takeaway from that conference was that presentations were completely scripted, low-impact, and devoid of two-way dialogue, despite that being the purported reason for the event. Questions from the crowd went mainly unanswered. Turbulence in the company was left unaddressed.

Many of us found it to be a fun party but professionally disengaging. You had 1200 senior leaders who wanted a dialogue and couldn’t get it. We were, of course, missing the point. This was propaganda, not discussion.

We walked away with less confidence than we had before.

I see Amazon now deepening its love affair with leader propaganda through its “Meet the Leader” series.

The most recent edition features Sarah Rhoads, the company’s VP of Health and Safety. This episode crystallizes three issues with leader propaganda which lead to the paradox outlined above.

No one in the audience cares that much about the perspectives of executives distant from their daily reality. They care more about their direct teammates and prefer executives focus on improving working conditions vs talking about themselves.

Staged interactions lack authenticity. No one feels anything from them, and no one believes them because they lack genuine humanity.

To the extent anyone pays attention, the details they notice degrade their confidence rather than bolster it.

Now that I’ve admittedly biased you, have a look at this video. I understand you may not have time to watch it all, but sample a few random snips to get an impression.

Immediate observations:

The video and article don’t make someone care what Sarah has to say. Aside from reciting her title, no foundation is laid to give her credibility. So the tendency for the audience to be aloof to the views of distant executives is not overcome.

The interaction is obviously staged, to the point of being clumsily pre-manufactured. It feels more like two droids trading ChatGPT outputs than a genuine exchange. This turns people off.

The closer anyone watches, the less confidence they will have afterward.

And here’s why.

People expect their VPs to exhibit strong leadership qualities, and there’s little of that here.

We hear a lot about Rhoads’ pedigree, the jobs she has held, what she has delivered.

What we don’t hear is who helped her get where she is. Who she helped along the way. Who inspired and influenced her leadership style. Who she has inspired. Certainly she has been mentored and supported to make it this far. But we don’t get any sense of that. It’s as if she’s done it all herself … no stories of team grit, recovery, or perseverance. Just personal successes, with a token mention of the “awesome people” who delivered the actual work.

This piece paints a picture of an individual flying solo, not a leader inspiring and elevating others to deliver team results. That may sound unfair, but it’s what we can derive from this brief heuristic.

And it illustrates a key risk of parading executives in this way. Given the lack of persuasive substance, how propaganda is received is tethered to pre-existing attitudes about the subject.

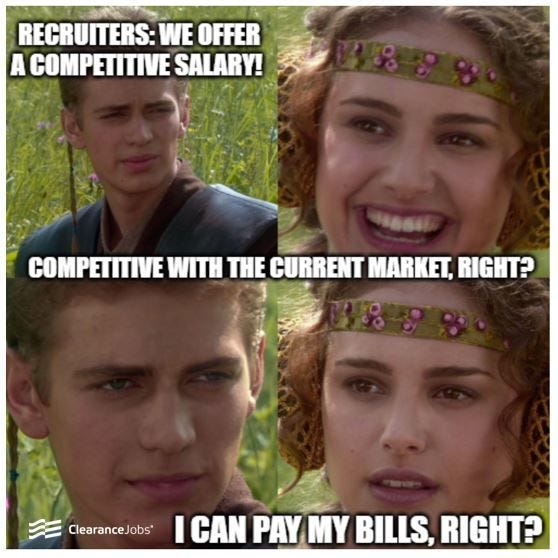

For example, if you say “we offer a competitive pay package,” that is a vagary without any real meaning. It can’t persuade. If someone already thought pay was competitive, this will confirm it. If they didn’t, it won’t change their mind.

In this case, there is no persuasive substance to make anyone confident Sarah Rhoads is a strong leader. If someone already thought she was great, this won’t dissuade them. If someone already thought she wasn’t great, this will reinforce that pre-existing view.

In this case, the perceived self-importance of its subject might entrench pre-existing views.

Sarah’s reputation in segments of the ops network is not good. Many leaders, some of whom I worked with over the years … some who enjoy my trust and respect … portray her style as toxic. Famously autocratic and forceful in her methods, she was known to publicly dress down others, often oversimplifying complex issues, zeroing in on minutiae, and driving people to try harder without providing additional support.

None of this made her ineffective. At the time, these methods were accepted in a fledgling UK network still working to build itself out.

But it remained a fun drinking game over the years for GMs to wonder how Rhoads and some others who drove the UK network's early growth would have fared had they been forced to compete in that same network years later … with dozens of superb leaders in the mix capable of getting results without crushing teams. A network where genuine leadership and team development were expected.

This is a compliment to Sarah and others for building something that developed into a much more complete and mature organization.

But it does rubberize the landing of propaganda efforts like this one. When people who have worked with her watch it, they just roll their eyes. They are unmoved. Their views are reinforced.

This is not to say the interview is all bad. You can discern the outline of a philosophy hard-earned in the unique, global journey of a high achiever who wants to bring the whole world along with her. Sarah’s safety pitch and philosophy of getting upstream to remove hazards is really strong, and it’s excellent to see someone with a deep operational background leading all of safety for the company.

But the takeaway message is all about ambition, individual performance, and individual progress. And the problem … is that this is totally consistent with Sarah’s reputation. So to the earlier point, to the extent this propaganda is accurate, it does more harm than good.

To the extent Amazon’s internal comms team recognize this message doesn’t resonate, they’ll feel compelled to shore it up with more propaganda, which instigates a vicious cycle.

Or maybe I will be completely wrong and it’ll be an internal PR home run.

But I doubt it. Because people hate being propagandized. And it makes them reject the message even harder.

One of my colleagues made a wonderful habit the past few years of using social media to tell the stories of his frontline workers. Those delivering at the coal face of operations have stories no less compelling than those who occupy the high tower.

His messages gave everyone a deeper notion of the identity of the individuals comprising his team, and of the team’s sense of unity and shared purpose. It was popular with the team because here was their boss, using his outsized megaphone to celebrate not the senior managers, but the rank and file. Making them celebrities for a moment gave them cherished recognition.

I’d love to see Amazon and other big companies do more of that sort of internal communication and less aggrandizing of those at the top. They should be imagining themselves at the bottom of an inverted pyramid, supporting everyone who does the work that creates value, and showcasing those individuals is a more worthy objective.

But if Amazon is to persist with its leader showcase, I recommend ditching the script, killing the spin, and letting people catch genuine glimpses.

It’ll resonate a lot more. And it’ll help the company avoid the propaganda paradox, which ends with broken confidence and chasm of emotional and intellectual distance between executives and employees.

Because people hate being propagandized. And it makes them reject the message even harder.

This was on my radar today, and now it’s on yours.

TC was an Amazon leader for more than 7 years, holding senior roles in four buildings and leading teams of thousands. He is now an independent writer and keynote speaker on leadership, applying lessons from his 33 years in private and public enterprise with the goal of helping build positive cultures and high performance teams.

“Corporate Communications” wasn’t even a thing until the 1990s. It sure sounds better than “Dissent and Disgruntlement Suppression.”

Is it too much to find a place to work that doesn’t generate cynicism and does generate joy? I had 4 assignments on active duty that brought me JOY. I was a valued team member making adequate pay with excellent benefits in well led high performing organizations doing important work. That was all I needed. Why is that so hard to find?

My mileage since that last assignment has been varied.