The Sheer Stupidity of Sweating the Small Stuff

Why broken windows theory should stay in criminology where it belongs

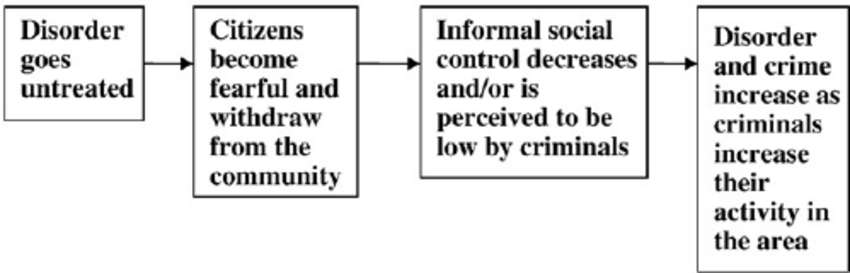

Broken windows theory is a popular idea from the world of criminology. It proposes a link between respect for an environment and criminality.

When you fix broken windows, you create pride in an environment which discourages small-time violations. As overall criminality reduces, the likelihood of more serious violations comes down with it.

And conversely, when you let respect for an environment degrade, darker things tend to follow.

This theory was planted in the popular imagination by the rejuvenation of New York City in the mid-90s. Bill Bratton, hired as police commissioner in 1993 by newly-elected Mayor Rudy Giuliani, cleaned up the city by focusing on small-time offenses that had an outsized impact on how citizens felt about the environment.

It worked well in the situation, but was afterward unduly popularized when Giuliani expanded it into a leadership philosophy and wrote it into a book. Back when he was still a broadly admired figure.

In the years since, this concept has been misappropriated by various organization theorists, gurus, and “content providers.” It’s been taught in management classrooms.

Over a generation, it has fruitfully multiplied in the infested brains of rank and file managers.

As a result, we are now seized with the notion that you should actually go out of your way to sweat the small stuff.

How many times have you heard one of these formulations from someone holding themselves out to the world as a management professional?

If you take care of the small stuff, the big stuff will take care of itself.

If you don’t care about the small issues, your people won’t care about the big ones.

The only discipline is perfect discipline. Everything matters.

These great-sounding phrases obscure fundamentally flawed reasoning. Let me explain why I think “sweating the small stuff” is the worst idea since ketchup and mustard in the same bottle.

These arguments are interrelated and overlapping. I offer no apology for that.

It validates top heaviness.

I can tell you in a matter of seconds whether an organization has too many managers by simply observing how they spend their time.

When someone is promoted to a given level, that advancement makes them feel responsible to make impact and justify their presence. If there are too many managers at a particular level, there won’t be enough legitimate issues to go around. What we see then is people who feel the need to look busy zeroing in on things way below their intended eye-line.

Air Force General officers should be focused on strategic matters. Not the dimensions of smoking areas. Not the temperature of the orange juice poured at the club.

But when we collide “small stuff matters” with under-employment created by over-promotion, we will find overpaid people studying the anatomy of a gnat’s ass.

It allows shit managers to justify their paychecks.

Amazon doesn’t have many traditions, but one which persists is for directors to physically visit and tour their business units periodically. This is a good practice which lets them assess operations first-hand and hear from the people doing the work.

But it’s also an opportunity for what I call stunt management … finding a way, no matter how great the team are doing, to make them feel inadequate. And hence, to be seen adding value.

When a building is performing at an elite level and is well-tended and organized, pickings for stunt management get slim. But in a warehouse the size of 20 football fields, you can always find a small housekeeping problem, like a dusty shelf, overflowing trash can, or crooked pallet.

Director-level leaders making top 2% salaries should be focusing on how to reduce dust generation in warehouses, not pointing out the obvious fact that dust has settled somewhere.

But by the magic of “small stuff” … pointing out trivial issues equates to adding value. It gets rewarded, and it continues.

It encourages zero-tolerance overreactions to small problems.

As a culture, the Air Force has done two things over the past few generations which have fundamentally changed the service for the worse.

First, it has criminalized minor mistakes.

Second, it has adopted a philosophy that mistakes are recoverable but crimes are not.

The result is really good airmen losing their careers and life horizons over painfully small stuff.

Like having an underage beer or failing to report someone who does. Like getting a speeding ticket. Like conducting an otherwise normal sexual engagement with a counterpart somehow verboten by policy. Like breaking curfew. Like missing a mortgage payment or bouncing a check.

There was an airman from a unit in New Jersey a few years ago who was prosecuted in court for being late to work twice in six months. Is there any more mundane or human frailty than failing to plan for traffic?

Getting infatuated with the idea that attacking small issues prevents larger ones is not only illogical, but destructive to an organization’s goals. You need people who can make mistakes, learn, grow, and recover.

And you need to understand with crystal clarity that there is no such thing as perfect discipline or an unerring human being. This is one of those two-types moments: there are people who admit to having broken the rules, and there are liars.

If you think I’m wrong, check out this book. You’ve probably violated several laws already today, and you’ll violate more before and during bedtime. In our culture, law has become a construct to hold us all at risk, with government deciding arbitrarily who will be prosecuted. “Small stuff” fixation perpetuates this.

The biggest sin: sweating the small stuff is a license to ignore real problems.

Those who have followed my work over the years are aware of my seething relationship with Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. It has always been a nasty, bitter, and shallow misery trench … a barren and filthy hellhole where jackasses roam free and morale goes to die.

At the height of the Air Force’s corporate dysfunction, the base was busy pumping out an 83-page supplement to the service’s uniform regulation. Because, you know, something like how to get dressed in the morning needs a lot of clarification, preferably in long and preachy paragraphs.

And while the base was busy cranking out simian gibberish about how to tuck in a t-shirt properly, airmen were packing their lungs with mold spores, contracting excrement-borne illnesses, and hacking up belly fulls of unsafe drinking water.

It took Congressional threats to move the needle.

And yet, a dozen generals cycled through Al Udeid to bigger and better things, touting their ability to tell airmen exactly how to suck eggs as proof of readiness for more.

And they were encouraged to do this by a false belief that getting people to pay closer attention to dress and appearance would make them more combat capable.

When the actual path to that goal was through the land of additional resources to better support and materially enable them … instead of painting over both mold and graffiti and pretending it was leadership.

In my recent podcast with Chris McGhee, we discussed the USAF’s suicide problem.

It’s an issue with immediacy and seriousness that should jar and clarify thinking instantly, yet has proven elusive for the service to tackle.

I believe the reason the USAF has a worsening suicide problem … after years of opportunity to address it … is simple.

It wants to address it for free.

No one has the stones to actually fight for and secure and provide the additional resources it will take to improve the conditions leading to its higher incidence.

So they avoid any conversation which might lead to the conclusion more resources are required.

And how do they do so?

By focusing on small stuff. Marginal stuff. Trivial stuff. And pretending this is a valid way to manage. And getting away with it.

Sweating the small stuff isn’t just a little bit wrong. It’s totally and completely inappropriate conduct for a responsible manager. Priorities exist. Resources, to include time and focus of managers, must map to priorities.

Anything else is buggery, whether intentional, reckless, or merely negligent.

Sometimes, you can move a theory from one context to another and it works.

“Moneyball” is a good example. Economic analysis of output per unit of input, it turns out, is a great theory for building a baseball team.

But you have to be careful moving theories around. Because more often, it’s like riding a jet ski in the snow. Same basic idea, but not quite the same in execution.

And sometimes, it’s like trying to ride a bicycle in lake.

Stupid, misguided, and often fatal.

TC is an independent writer, speaker, coach, and consultant specializing in organizational leadership. He has 33 years experience together with graduate degrees in law, strategy, and organizations.

Boy the AlUdeid comments were so true. We were setting manholes and adding conduit and fiber cable to the tune of miles per week and we were frequently badgered on dress and appearance by those who live in the AC.

“Where jackasses roam free, and morale goes to die!” Lmao. So true, Tony! Love your insights and your writing. Cheers