In my travels to Ireland over the past 10 years, I’ve picked up a wonderful phrase (by the way: go to Ireland, and talk to the cab drivers … each of them is like a rolling firehose of folksy wisdom).

The phrase is “my ghost told me.” The usage of this phrase is that something bad was about to happen, and then a voice seemed to whisper at just the right moment … to step in a different direction, make a different decision, or hesitate at the critical moment. Disaster averted, because of timely advice from a past version of oneself.

This is a wonderful way of thinking about the value of prior experience and how it informs judgment and intuition. The idea is that out there in some ephemeral plane between the vague parts of our consciousness we don’t fully understand and the concreteness of reality, versions of our former selves roam, each possessing important knowledge we learned at key moments in the past.

These ghosts intercede at key moments, when this prior knowledge is most critical, injecting what we’ve learned into our decisions to keep us out of trouble.

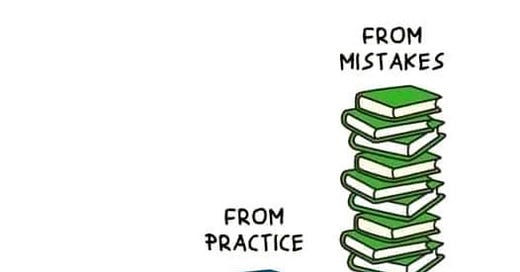

What I’ve noticed over the course of time is that experience is a lot more valuable than theory or abstract ideas when it comes to success in dynamic endeavours, such as leading teams of people under intense operational conditions. And the best kind of experience is that gained through mistakes — preferably ones made by someone else.

What I’ve also noticed is that everyone seems to agree about these basic propositions. But when it comes to applying them in large-scale organizations, it’s actually rare to see them operationalized effectively.

This spurs me to offer a few thoughts on the matter.

Theory Has Limited Value. Standing alone, theory doesn’t do a lot to inform judgement or equip someone for success in a dynamic enterprise. No matter how powerful the ideas, they tend to gather into woolly clouds of vague understanding which float around in the consciousness but never really form into a coherent foundation upon which to base decisions or actions.

Not All Book Learning Is Equal. While the above suggests that someone armed only with what they’ve learned in an academic setting will not be as prepared for a dynamic environment as someone with experience, not all debutantes are built alike. Exposure to theories which leverage histories, traditions, and case studies based on situations faced by others can create a degree of vicarious learning superior to the purely theoretical.

As a required element of US Air Force pilot training, students learn about prior accidents by reading case studies which set context, describe the chain of failure in detail, and allow students to empathize with those who experience the mishap first-hand. This method of knowledge transfer gives students a vivid and effective grasp of the different ways they can get themselves into trouble. Their ghosts are able to talk to them a bit more effectively as a result.

It’s Unnecessary to Choose Between Theory and Practice. The premise thus far suggests that we should always favour immersing someone in their job to get them direct experience instead of feeding them theories which are unlikely to stick. But this is a false dichotomy. The best model interlaces these two elements, providing a thin foundation of theory to create an outline for learning in situ, then providing experience which makes sense out of that theory, then introducing additional theory which encounters a mind better able to contextualize and absorb it. By alternating these elements across time in a system of continual learning, it’s possible to make theory more valuable and performance more effective.

I’ve noticed this dynamic playing out in different ways during my time leading warehouse operations teams in a large retail organization. New managers are given a baseline of theory about the business but struggle to make much sense out of it until they’ve had a few months and a few intense sequences of experience in the live operation. Revisiting and deepening those initial ideas again after getting some experience, many lights bulbs get lit and the manager goes back to the role feeling more grounded, confident, and effective. This underscores the importance of having a continuing programme of education to reintroduce key concepts at the right moments to constantly develop the skill and confidence of the team.

This leads, however, to a trap often encountered by big organizations. Once everyone notices that continuing education creates highly-effective teams, the temptation for the larger business is to replicate successful approaches across the entire organization. Implementing a continuation training program at scale, with a predictable resource model and standardized method, tends to create a bureaucratic constituency focused on delivering development as a corporate process. This leads to process fixation. By focusing on how to systematize it at a large scale and with high efficiency, we move away from a tailored approach which notices what each individual needs at each stage.

Scaled approaches that operate on deadlines, often driven by when the most cost-effective contractor is available to deliver the content, end up compromising the impact of continuing education by moving focus too far away from the customer (in the case, the recipient of the content).

This is pretty much the danger with anything successful, which as a result grows in popularity until it becomes bureaucratized, efficiency overpowering quality as the key performance indicator.

Failure is the Best Teacher. Getting something wrong has an important psychological impact. It breaks down our normal thought process, makes us question ourselves, causes us to review our actions and decisions in excruciating detail, and ultimately leaves us vulnerable to the absorption of new knowledge in a way success cannot. This of course assumes that failure is acknowledged and embraced as a learning opportunity, which assumes a positive organizational culture.

This is where I’ve seen leaders go wrong in a particular way. It’s common for leaders to mouth along with the unassailable principle that failure is necessary for learning over time. Many even mean what they say, and refrain from actions in the wake of a failure which might chill the willingness of others to risk failing in the future. But this is not enough.

To cultivate a true learning organization, a leader needs to proactively, notoriously, and constantly demonstrate top cover of the team. This means aggressively creating a feeling of psychological safety so individuals have zero doubt in their minds that honest mistakes, even if anecdotally costly to the organization’s objectives, will be embraced as learning opportunities rather than drawing scorn, backlash, or embarrassment.

The Air Force’s aviation community is exceptionally good at this. Errors made with the proper intent but the improper execution are opportunities to learn and improve for next time. Debriefs often last hours, with each frame of execution reviewed to break performance errors down into minute detail. This requires a culture of mutual trust and humility, which in turn requires leaders who are careful with the vulnerability exposed by individuals engaged in an earnest effort to learn from their misfires.

Most Failures are Disguised. Just as important as extracting value from obvious failures is taking the trouble to learn from what seemed to go well overall. Hidden in every successful event is a catalogue of lucky moments, close calls, and avoided risks that, with a few twists, could have changed the whole story. In organizations with a tireless commitment to learning, successes are peeled apart and studied.

It’s important to note here the reality of accidental or incidental success. If you overtake a slow-travelling car on a bending country road and it works out fine, you tend to count that as a success. You don’t think critically about what might have gone wrong or ask yourself why it was necessary in the first place. What made you feel you needed to rush? Did you plan the right amount of time for the journey? Did you leave on time? Did you take the best route from A to B? These questions sit idle because you didn’t crash.

Because of a powerful psychological bias leading us to believe that what worked before will continue to work, you might make the same series of mistakes again with a different outcome. That is, unless you pull apart your success and acknowledge the elements of it that you didn’t create or control.

Theory is essential. Experience is worth exponentially more. Experience and theory interwoven, even better. Mistakes made in the arena while gaining experience are the deepest wells of learning opportunity.

But all of these propositions assume a cultural commitment to learning which, while we all seem to agree is best for everyone involved, continues to be a rarely achieved thing.

Tony Carr is an American writer, theorist, and restless learner with 30 years experience leading dynamic operations. He writes from his home in the UK.