Once upon a time, there was a farmer. He needed to protect his hen house, so he asked one of the local foxes to stand guard.

He knew foxes enjoyed preying on chickens, but he he was confident that the fox was a good guy. He discussed the job with the fox and appointed him to the role.

Predictably, the fox held the gate open for his friends from the ‘hood. They proceeded to feast on the hapless chickens.

Beneath the farmer’s outward expressions of shock and dismay, there was a knowing resignation.

It was as if he knew all along what the fox would do.

Which brings us to the subject of the Inspector General (IG).

The IG is designed to look like a shield against the abuse of power. But it’s a fox guarding a chicken coop.

And as many military members have learned over the years, the IG does not exist to protect whistleblowers. It does not exist to police abuse or document fraud.

It exists for one reason, and that is to protect the chain of command. Those who have believed otherwise have suffered the grim fate of hapless chickens.

It’s been clear to interested observers and experts for a long time that there are only two instances in which an IG will find against the chain of command and in favor of a complaining servicemember.

They are:

When evidence already available in the public domain makes the avoidance of an unfavorable finding impossible. Example.

When an unfavorable finding is otherwise in the interest of the chain of command. E.g. when a scapegoat is needed or the organization decides to turn against a toxic individual in an effort to reclaim or preserve its moral authority. Example.

At all other times, raising an IG complaint will almost certainly lead to frustrating oblivion. A long wait for justice punctuated by disappointment. I’ve seen it hundreds of times.

And yet, I return to this issue after a few years away only to learn that people still commonly believe in and endorse the IG process.

I don’t pretend the power to change that. But I intend to use my little corner of the internet to challenge it.

People need to understand what the IG isn’t. To advance that understanding a degree or two, I shall digress into a brief tale. It’s an oldie but goodie from a domain I know well: the occasionally unfortunate fuckery of Air Force senior officers, whose certainty sometimes travels at a higher velocity than humility, curiosity, or advice.

To make this story more digestible, I must detour briefly into the Air Force’s official position on the role of the IG.

Here’s something an Air Force spokesman said to me once on this subject. It remains the standard talking point, rolled out absent noticeable alteration, nearly a decade later.

“[I]f a person does not feel a situation or circumstance such as a perceived wrong or violation of law or policy can be resolved or adequately addressed within the chain of command, then filing an IG complaint is certainly an option available to that person.”

This sounds intuitive and kinda cool. If you were shopping for a can of IG in the store and this was printed on the label explaining what it does, you would feel pretty good about buying it.

After all, what an excellent function, right? If your complaint can’t be resolved by the chain of command, this probably means the chain of command is the problem. And having some recourse and protection in this case is reassuring since the chain of command signs your paychecks and controls your life.

The mere fact of the IG’s existence, especially with this statement as a backdrop, implies that occasionally, it will provide a remedy to those unjustly done.

But this is where it gets tricky, and the small print on the label becomes important.

That small print can be found in Air Force Instruction 90-301:

“IGs serve as an extension of their commander by acting as his/her eyes and ears to be alert to issues affecting the organization.”

Wait.

“Extension” of the commander. That means the IG is working for the commander. That means the IG is there to protect the chain of command.

Less reassuring.

It’s not just my preference for animal metaphors when I say this phrasing construes the IG is less a watch dog and more a guard dog. Or maybe more a lap dog. Certainly a dog.

Which makes it unsurprising that IGs routinely work to turn off complaints rather than pursue the right outcomes for those complaining of abuse or reprisal.

Which brings us to the case of an instructor pilot at Laughlin Air Force Base about a decade ago.

This pilot was placed under investigation for drug use, which was later forensically disproven. But at first, during the “presumed guilty” phase, his group commander was pretty sure he needed to be destroyed.

After this pilot was initially interview by investigators, the group commander, an Air Force colonel, issued an order insisting that he:

“not discuss the details or nature of your interview, the investigation overall, or anything related to said interview or investigation with anyone except me; your squadron commander; [investigators]; or your Area Defense Counsel (ADC).”

Astute readers will note several fundamental deficiencies with this order.

First, it provides an extremely limited list of permissible contacts. In doing so, it restricts the officer, who is under career-threatening criminal investigation, from seeking counseling from a mental health professional, chaplain, spouse, other family member, confidante, pet cat, Avon Lady, or anyone else the officer might turn to for help.

In this way, the order contradicts principles of resiliency and suicide prevention. Airmen in crisis are socially isolated, emotionally vulnerable, and at elevated risk of self-destructive thoughts and actions. The opportunity to associate freely enough to keep such tendencies in check is important.

Second, the order is unlawful. The commander who issued it, not a judge, misfires in attempting a judicially-styled gag order. If such an order were deemed important to an ongoing investigation, it should have been sought from someone qualified to consider the legal merits and issue it properly.

A properly qualified order would have taken into account how limiting speech and association can impede the ability of someone accused of a crime to raise a proper defense. These impositions must be weighed against the risk of a compromised investigation.

The improperly issued order is overbroad, robbing the accused of any ability to marshal appropriate advice, enlist witnesses, or seek representation.

The order also assumes the officer will consult with a military defense counsel rather than seek out a civilian lawyer. This unacceptable limitation on due process makes the order unlawful all by itself. It also underscores that the colonel had no idea what he was doing.

Having been given an unlawful order, the accused did what he was entitled to do and indeed what our system expects: he violated the order to the extent necessary to get the counseling he needed and to organize a defense for himself.

When the colonel learned of this, he retaliated, issuing the officer a formally documented admonishment. The colonel cited disobedience of a direct order, ignoring that this only applies only to lawful orders.

Having been unlawfully restricted and tarred with an administrative reprisal, the accused officer did what the system expects. He did what the quote from the spokesman above suggests. He filed an IG complaint.

That complaint alleged the colonel had violated a plentiful array of laws, including defense department instructions concerning counseling services, chaplains, and mental health services. It also called into question the consistency of the colonel’s actions with the First Amendment as well as Art. 38 of the UCMJ, which provides that an accused member is entitled to seek and employ a civilian defense attorney.

The complaint also alleged the colonel had violated Title 10 of the US Code, Section 1034, which provides that:

“no person may restrict a member of the armed forces in communicating with a member of Congress or an Inspector General.”

This provision is clear and unambiguous. It means military superiors can’t bully and intimidate subordinates into political obedience by issuing unlawful orders under the false color of legal authority.

It means, in this case, the military commander involved wasn’t authorized to give an accused a definitive list of permissible contacts which excluded the IG. In doing so, his order almost certainly violated federal law.

Given so many clear violations and the reassurances of how IGs help when the chain of command can’t resolve stuff, the officer involved expected a positive resolution from the IG. This was reasonable to expect.

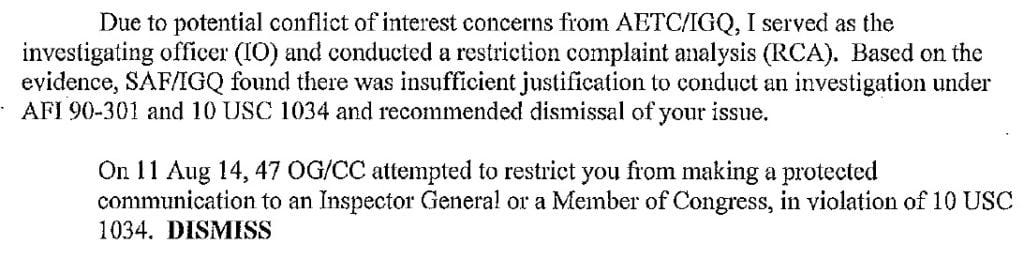

Instead, here’s what he received after a five month wait:

Inscrutable and ultimately pathetic.

It arrives at an incorrect conclusion, which would be bad enough. But it also fails to provide any analysis upon which that conclusion is based.

This effectively denies the complainant any opportunity to challenge the finding, since by giving no rationale, the response renders itself unfalsifiable.

It also addresses only one violation of the half dozen cited by the officer in his submission. What about the rest of the laws that were broken?

While distressing, none of this is surprising. Which is even more distressing.

We can’t escape the conclusion that the IG exists to help the chain of command minimize the impact of its abuses and mistakes, not to genuinely provide redress for those victimized by abuses and mistakes.

In current form, the IG complaint resolution process is a cruel joke. It fools people into believing they have a means of seeking accountability when the chain of command abuses them.

In reality, it’s a continuation of that abuse … barely obscured behind a thin beard of faux concern. It fools those who believe most in the positive intentions of their organization. Which is just disgusting.

The IG process is a high form of bureaucratic cynicism cloaked in just enough pretension to prey on those already scorned by role models to whom they lent their trust.

When an IG behaves like this, it legitimizes command misconduct rather than addressing it. This makes it a means of corruption rather than a check against it.

This is something I need to put on your radar. Because the first step in getting something broken to work correctly is to define the problem. To actually expose its true nature.

When it comes to the IG, what’s going on is that US government agencies are being policed by people who have an interest in protecting them from accountability.

Which is to say they are not policed at all. And therefore unaccountable.

If my diatribe doesn’t persuade you, or if it does and you want to go deeper and become more active about it, check out this article from Francesca Graham, who is doing a lot of work to raise the decibel level on the decrepitude of this process.

Within that article, you’ll find linked a video where a currently serving bureaucrat unsuccessfully rationalizes the lack of accountability for tainted drinking water poisoning military families.

I’ll link it here too, because I bear no guilt for rage-farming when the rage is justified. Start at about 10 minutes if you really want to piss yourself off quickly.

“It’s accountability within the system we have established.”

Accountability within an unaccountable system. Which, by definition, is none at all. And that’s what you can expect when you let a fox guard the chicken coop.

It turns out the farmer doesn’t really give a toss about protecting the chickens. He just needs observers to believe he is making an effort, therefore keeping the chicken advocates at bay so he can continue to run his farm as he sees fit.

In the hundreds of cases I’ve seen, this is pretty much exactly what the IG has delivered. It is not there to help.

If that comes as a surprise, then I am sorry, and you’re welcome.

TC is an American writer, veteran, and former member of the advisory board at the Center for Defense Information at the Project on Government Accountability.