Lots of positive media for Amazon lately. “Most Admired Company” according to a survey of executives and analysts. $30B profit in 2023, capping off $80B in four years. Even named “Top Employer” by the Top Employer Institute.

(Though in fairness, this is a bit like me paying a fee to be named Top Writer by the Top Writing Institute).

A neutral observer might conclude it’s all sweetness and light. But it isn’t.

I found the experience of working in a senior role at Amazon to be a story of both successes to celebrate and opportunities to improve. I am moved to share what I learned by relating what I experienced.

Some of what follows isn’t pretty. If you’re a fan of Amazon, brace for impact.

Last year, I made the decision to leave Amazon after an eventful 7.5 years in its UK fulfillment network. It was a complicated personal and professional decision which I will partially but not fully explain.

A lot happens in the Amazon environment in a width of time, so it’s like dog years. Basically I just finished a 50-year career. And in some ways, I do feel undead. Zombified by the sheer relentlessness of the journey.

As I reflect, I wish I could claim revelation. I wish I could say I grasped the sword of experience and pulled it from the stone, seizing a magical weapon of enlightened management genius forged in the fires of the counter-intuitive.

But what I learned is what I already knew. Which is maybe why I heard the bell of doom tolling before many others, including many who yet don’t hear it.

When companies get big, their natural tendency is to become shit places to work.

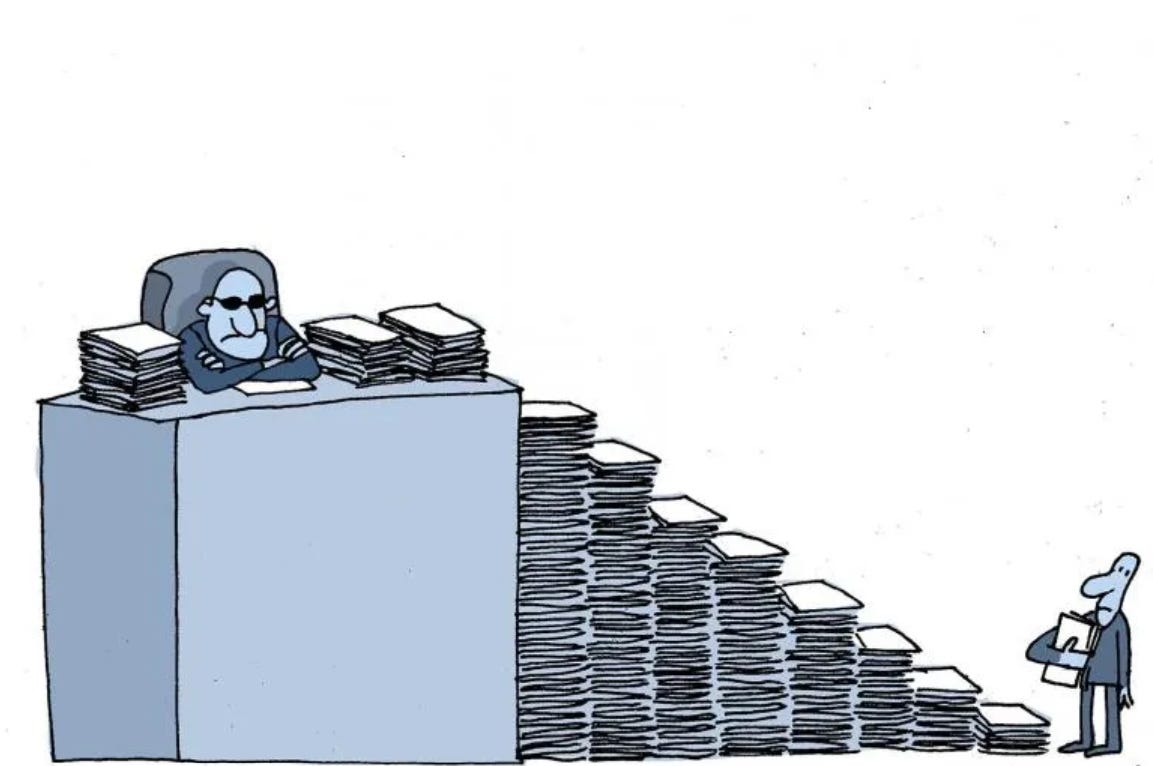

As organizations scale, decision makers become distant from action. No longer able to personally direct everything, they face a decision.

Either:

(a) scale by developing others in a shared value system and trusting them to execute based on leader intent; or,

(b) create process, structure, and bureaucracy as proxies for that intent.

Most organizations start out preferring the former but default into the latter.

Because it promises efficiency by turning human activity into an orderly commodity exchange.

Because it’s what gets taught in MBA classrooms.

And because as executives lose intimacy with the action that creates value in their business, they also shed the empathy and humanity they once felt and cherished. Save, of course, for those who were always heartless cyborgs.

As businesses get massive, executives come to prefer order and predictability. And they prefer the easy exercise of fly-over authority to the messy and strenuous exercise of influence.

Absent intentional, proactive, genuine effort to the contrary, big corporations will devolve into contemporary salt mines. Everyone will be miserable except for senior executives and shareholders, though others will pretend or rationalize to the contrary. Because that’s what you do when you need to keep your job and feed your family.

This isn’t just an Amazon problem.

But it is an Amazon problem, and important context for what follows. During my tenure, the network more than tripled in size, trading its scrappy and entrepreneurial spirit for something else.

My journey wasn’t all bad. I met some exceptional people. I had a hand in hiring and developing some superior professionals. The growth I was able to experience in a second career was way beyond what I expected. And there were moments of genuine camaraderie … shared endeavor and fun powerful enough to forge lifelong associations.

But the positive lessons I’ve come away with are in many cases my own fabrications from negative examples. Amazon was mainly a master class in what not to do.

Here’s some of my journey and what I learned.

Amazon’s value system was real …

One of the reasons I chose Amazon was its commitment to a framework of core values, expressed as leadership principles. I’d heard from others that the company baked these principles into the day-to-day experience of working there.

For years, I found this was true. And it was the number one reason I continued.

The principles were ever-present. They were real commitments. In daily performance, in talent reviews, in hiring, in administrative processes, they were always there, guiding action and analysis.

… And then it wasn’t.

Share price uber alles. That’s a modern corporation, no matter what it says on the label.

After the pandemic, Amazon’s share price took a temporary hit as inflation and interest rates exerted downward pressure on household spending.

The result was abject panic.

Never mind that Amazon’s losses tracked largely with overall market trends. Never mind that the company had made money hand over fist for years. There was no rainy day fund and no patience.

Amazon started melting its leadership principles. Operations and support staff cuts were enforced autocratically. Senior managers positioned to gauge the impact were voiceless. A spreadsheet detailing the cuts was issued like a stone tablet from on high. It wasn’t a plan. It was a commandment.

The absence of opportunity to challenge something central to operational delivery was a 180-degree reversal of the culture I had previously experienced. We were going to create management staffs that couldn’t possibly support their associates to a high standard, and there was no debate to be had about that.

This made it obvious to me that the leadership principles were fair-weathered. Which is to say they weren’t principles at all, but unreal slogans.

I had good leaders who looked after me …

When I needed to step away to deal with family issues or weather the loss of my Dad, my line manager understood and supported. After a health scare in 2019, the business gave me time to recover. It was the genuine care and connection of my manager that convinced me to continue my career at that point.

There was a tacit recognition that I was working silly hours and adding a lot of value, so it was fair and sensible to give a little latitude when life happened.

This is what happens in a positive culture.

… And then I didn’t.

In early 2023, Andy Jassy’s molecular obsession with the timekeeping of corporate employees seemed to infest the brains of others.

Alongside peers, I found myself explaining the details of my diary, accounting for my chosen balance between physical and virtual presence in the office, and rationalizing how I was achieving results rather than what I was delivering.

I wasn’t having this level of micromanagement, especially while delivering superior results. The team I’d built crushed a difficult launch operation with my hand on the tiller. I’d voluntarily doubled my commute to step up for the business. I’d been rated a “role model” on Amazon’s leadership principles and built a strong track record and reputation.

And then suddenly, I wasn’t trusted as a General Manager.

Then again, it just stands to reason. Being flexible for the network meant I was shuffled through six line managers across four regions in less than 2.5 years. I finally found one that didn’t like the cut of my jib.

After a period of illness, I returned to a work environment that felt hostile. My name had been dragged through the mud in my absence, some of my decisions publicly questioned when I wasn’t present. Unkindness to the absent is a hallmark of toxic organizations.

And yet I was reluctant to blame my line manager, who was inexperienced and struggling to reconcile multiple conflicting styles across her massive region. The span of control, number of reports, breadth of financial accountability, and sheer weight of obligation upon this individual was excessive. I don’t believe they were developed or equipped by Amazon to handle it.

Thing is, I’ll stand in the bread line before I’ll endorse a toxic environment by working in it. So this situation was the final hammer blow to the final nail in my decision to resign. It was a sad contrast from just a few years earlier, and a symptom of allowing values to be neglected in the process of scaling.

I’d like to tell you this element of my story is unique or just some personal beef with Amazon. But I’d be lying on both counts.

I got actionable feedback …

My first several roles at Amazon came quickly, with team sizes growing from a few dozen to a few thousand in less than four years.

The propellant for this rapid growth was clear, actionable feedback. My managers took an interest in helping me accentuate my strengths and address my opportunities. Feedback was constant, and so was my growth.

My first few managers were exceptional. Every time I started to get even faintly comfortable, they’d stretch me a little more, let me struggle enough to open my mind, and fill it with gold-plated discovery.

… And then I didn’t.

In early 2020, I was nominated to be a site leader, which is Amazon’s business label for general manager of a warehouse.

The process was to compete at a panel. This hadn’t previously been the process, but as the business scaled, senior leaders who had been promoted based on their performance slammed the door shut behind them. Panel auditions were interposed to add a layer of assessment on top of actual performance.

And frankly, to provide a vague and subjectively defined process giving a small number of senior managers arbitrary control over which individuals they wanted to elevate in the business.

I played along, preparing dutifully for the panel, which involved answering behavioral questions with examples illustrating particular leadership principles.

I felt I’d performed well, and waited impatiently with naive optimism for a verdict. I say naive because for a brief moment, I believed I was involved in a fair process where the panel would objectively call balls and strikes.

Eventually, I was summoned into an office to have a phone call with my director, who informed me in about 90 seconds that my 90-hour investment in preparation hadn’t been enough.

Bizarrely, I wasn’t allowed to know why. When I probed for feedback, he struggled to provide any. He said I had pretty much nailed the panel. He spouted a few vagaries that didn’t make a lot of sense. His advice was to keep doing what I was doing and try again.

Try again how? Change what?

The feedback wasn’t actionable. It didn’t explain how I could improve, or even how I had fallen short. I assumed someone else had performed better. But that didn’t bring me any closer to knowing how I could win next time.

Squinting into the opaque veil of the process, I developed the impression I and others had been used as denominators to make a predetermined process appear competitive. No other explanation explained the circumstances and outcome.

Manipulating people into expending vain effort to compete for something they have no chance of getting isn’t cool. Even if it is common practice in life, love, and war.

Changing absolutely nothing about what I was doing, I competed again seven months later, delivering no better a panel performance. And I was successful, for reasons I still don’t understand.

I include the preceding paragraphs on behalf of myself and countless colleagues left disengaged by internal promotion panels in Amazon operations. It’s a multi-year open secret how shitty and disengaging these panels are.

Yet, the paper promotion process is no better. I’ve lost track of how many colleagues have been passed over for promotion based on a document review conducted by distant and aloof technocrats lacking the first clue about the individuals whose fates they are deciding.

Promoting people based on how well they play a game is not just wrong, but bad business. When you promote based on results, you get stronger results. When you do so based on how well someone plays a stupid game, you get more gamesmanship.

Ever try to get anything done with an organization led by game-playing pragmatists? You can’t turn a wheel.

Disrespect was legitimized.

There’s some shit you just don’t pull. Like, dishonorable enough that you have to believe for someone to tolerate it, they’d have to give over their dignity and lay low enough to use a snake for a pillow.

When such things happen in an organization, respect isn’t prevailing.

After I failed my first site lead panel in 2020, it was made clear to me I needed to move to another role in a different building in order to preserve my chance at progression.

Somehow, my four years of strong performance in one of the toughest buildings in the network was unconvincing. I needed to show more.

“No problem,” I said, with earnest humility. I accepted that I needed to persuade more people what I was about. So I played along. I wanted the chance to lead on a bigger platform.

My manager, GM of our building, was in the promotion process himself. I had proxied for him and run our warehouse for periods of time as he auditioned for a directorship.

His promotion would create a vacancy where I was already established, creating an ideal opportunity to lead on an interim basis and show decisively that I was ready for more.

Unfortunately, the faceless empowered were averse to common sense. Apace with their mindless bureaucratization of our growing enterprise, there was an arbitrary edict from the high tower stating their would be no more interim appointments.

If my boss got promoted, a permanent backfill would be hired instead of me or anyone else “stepping up” to cover.

Accepting this, I took a temporary appointment to Amazon’s warehouse in Tilbury, southeast of London. There I would have the chance to demonstrate I could thrive with a new team in a different context. It was the largest warehouse in the Amazon’s entire European network, and I was excited for a chance to contribute and grow there.

But it wasn’t all sweetness and light.

No sooner had I relocated and started my new role, it become public knowledge that my old boss was getting promoted and an interim site leader was being appointed in my former building. Someone, I don’t mind saying, less proven for the role. The goalpost had been moved overnight. The joke was on me. So much for no more interim appointments. Someone had wanted me out of the way, and I had naively accommodated. Because I trusted and believed in my leaders.

The appointed individual proceeded to under-perform over the next year before relocating to another UK warehouse, then to the US network, then out of Amazon not long after and without further progression. As a fascinating sidenote, she’d been pushed for the interim appointment by a since-disgraced former Amazon director rounded up in a child sex crime sting.

If you’ve ever pined for a jolting, horrifying advertisement of the dangers presented by the germ-infested underbelly of cronyism, there you have it.

I had a great tour in London. I learned a lot. Massive team, huge challenges, superb teammates. I cherish it. I’m actually glad it worked out the way it did, because I grew a lot from that tour.

But mainly I’m just really glad I could get out of the way so a sponsored ingenue could use what me and my teammates had built as a pummel horse before predictably exiting from a misfit career.

Expectations were unstable.

If you’re an Air Force veteran reading this, you might remember how things got so chaotic that people were leaving service just to settle their lives down.

Stable expectations mean a lot. They are strong arguments to join a big company. But alas, it’s a trap.

One of the contradictions of large organizations is that the more bureaucracy takes over, the less stable expectations become. This is because bureaucracies serve as art houses for the curation of absurdity. Just when you think you’ve seen it all, they will shock your senses.

In 2022, my job was to stand up a new Amazon warehouse in Liverpool. What a fantastic opportunity. I got to hand-pick my team, interact with new elements of the business, expand my own expertise, and create a positive organizational vision and culture from the ground up.

It was also an chance to be cost-conscious. My team and I were committed to driving costs to an absolute minimum through process innovation and responsible risk acceptance.

We saved Amazon most of £1M in avoided cost.

The launch was smooth. Stellar. Universally praised. No one needed to manage us. The foundation of operational excellence we built carried the site to lofty heights on Amazon’s official scorecard. The site was in the top 3% of over 120 buildings of its type worldwide a year after its first shipment.

Along the way, I’d achieved the company’s Bar Raiser certification, graduated from its Director course, and voluntarily invested substantial time to develop leaders and teams across the network.

My reward came on compensation day in early 2023, during Amazon’s share price fever dream. My manager released my compensation statement to me a few hours before our scheduled call to review it.

When I saw the statement, I understood why she’d waited.

My reward for being a conscientious and committed Amazon leader, for employing my influence, brand, and reputation to project its leadership principles far and wide while stuffing as much money into its shareholders’ pockets as possible, was a 20% year-on-year drop in compensation.

All my discretionary effort landed me no better than I would have been by being lazy and risk averse.

This is the textbook definition of not being valued for what you contribute.

The pay cut took me back to a point inferior to where I had been before my last promotion, nullifying years of work spent fighting for advancement.

This isn’t a snowflake moment. I wasn’t unique. Most salaried Amazon employees took a beating on pay in 2023, some by up to 50%.

I expect there will be pay beatings in the current year as well, despite huge profits.

The reason is simple: during a time of downsizing, the corporation is perfectly willing to alienate employees and trigger voluntary resignations. It doesn’t say so out loud, which is a failure of transparency corrosive to its “Earn Trust” leadership principle.

Had my dip in compensation come with candor, transparency, and reassurance that my deeds were seen and appreciated, I would have felt differently about it. But there was none of that. My manager dismissed my questions and hijacked the call to discuss trivialities.

While pay wasn’t my reason for resigning, it certainly didn’t help. Especially in the context of a historically profitable and successful company consistently refusing to pay people properly.

Hourly pay for Amazon’s employees had also been a bone of contention for years, declining from market leading to market mediocre just as revenue growth exploded.

There came a point where we were told to stop raising it as an issue, despite it being the number one topic most associates wanted to discuss.

Eventually, I was no longer willing to stand in front of my employees and tell them what a great deal I thought they were getting when I no longer believed it.

Many Amazonians who pulled a heavy oar during the pandemic felt hard done by in the aftermath. And they had a point.

You have to go back seven years to find a net quarterly income of less than $2B or a trailing 12-month net income of less than $5B. Yet employees who powered all that growth were the first orphans of a couple quarters of income still profitable but marginally below projection.

Given not a single unprofitable quarter since 2014, Amazon’s decision to slash employee compensation over what it likely understood to be a momentary share price fluctuation is cynical, and feels opportunistic.

Amazon’s shareholders have enjoyed a 706% return on investment over the past decade, powered by the sweat of workers slapped successively with the palm of pay stagnation and the backhand of inflation.

The company has lost track of how its value is created. It is not created by executives with their asses planted in swivel chairs. It is created by front-line employees.

A company that doesn’t value its people properly is bad enough. But one that claims at every turn to do so while not doing so is a whole other thing. It’s not a situation which will attract or retain people of character.

Looking back, the hourglass of my patience was overturned at “Ops Live,” a 2022 summit for Amazon’s senior operations leaders in Nashville. There we gathered, expecting meaningful interaction with the company’s senior VPs and the CEO of worldwide fulfillment.

What we got instead was a deluge of internal propaganda.

Here’s why everything is great. Here’s why you should be optimistic. Here’s a series of teleprompter speeches and semi-scripted Q&A sessions.

But good companies don’t need to convince themselves of what they’re about. Good companies don’t waste valuable opportunities for interaction on hollow cheer-leading and statements of the obvious. Bureaucracies alone are infatuated with glorified, theatrical meetings comprised of one-way communication.

Ops Live should have been cancelled. Its costs, including hiring Bon Jovi for a private concert at the Ryman Auditorium, should’ve been divided into thousand-dollar loyalty bonuses for veteran Amazon associates who had stood strong and pulled the company through the pandemic.

Gathering to waste money under the banner of needing to save money was a signal Amazon had scaled itself into a bureaucracy. Because it is the only organizational form comfortable with such contradiction.

When I got home from the conference, I told my family it had been a great time, but I expected to leave Amazon in the next couple years. I hoped things would change, but the cultural direction of travel was painfully clear.

I’d love to tell you the darker aspects of my journey were unique, but the things I describe happen all the time. In fact, I reckon my journey had fewer potholes than most. I knew others passed over for promotion without useful feedback and not given another crack. Still others never given chances at promotion because someone didn’t like their style.

I’ve known too many Amazonians who’ve fulfilled roles above their paid level for extended periods, sometimes years, without being given the level and pay reflecting their contribution. Trusted, relied upon, exploited. But not recognized and certainly not paid. This is alarmingly commonplace in Amazon’s HR organization, which is supposed to police such things but is instead one of the worst offenders.

The narrative of Amazon as a top employer or great place to work needs to be counterbalanced and questioned. What it really means to work there needs to be transparent.

In particular, I want fellow veterans, actively recruited and often attracted to the company, to understand some of the reasons why it remains a carousel of employee turnover.

Paradigm shifts are psychologically powerful. Once I had made the decision in early 2023 that it would be my last year with Amazon, everything that occurred looked grimmer through the new lens.

A program to address frontline manager overwork languished for a fifth consecutive year. Flashing red warnings that a sustainable workload had been left behind the scaling process were not only ignored, but the network doubled down by reducing manager headcount.

And as the calls for “more with less” … which is hate speech in my book … began gaining volume, I heard senior leaders mocking the value system. Likening calls for improved associate pay to being “Earth’s most naive employer” was just one of the more ridiculous phrases utilized to push challenges into the margins.

For the sake of the company’s 1.5M people and its $1.6T market capitalization, I’m hoping it won’t continue the lurch toward typical rinse-and-repeat corporate chicanery which has seemed underway since Jeff Bezos stepped down.

Be proudly different, as it once was.

Be excellent for all customers, including the employees who are ultimately the customer base for its several hundred executives and directors.

Be a good enough employer to validate good PR and prove it wasn’t purchased.

Create a positive enough culture that people who otherwise want to be there don’t get alienated. This will mean resisting the march of Day Two bureaucracy.

Learn.

Here’s the topline of what I’ve either learned or re-observed from my Amazon experience:

You can’t scale without trust. Or more precisely, you can use bureaucracy instead, but you’ll lose your identity and ethos in the process.

Scaling means balancing imperatives. Every manager is a leader (people, teams, values, vision, culture), a manager (priorities, adjustments, campaigns, metrics, financial performance), and an administrator (compliance, policy, regulation, documentation, order, organization). These imperatives must be constantly re-balanced and each of them respected along the entire spine of the organization. When mid-level managers respect this principle but executives let financial performance squeeze everything else out of the frame, misery and defeat take over.

Transparency is key. Don’t play games with people. Don’t prey on their good nature. Expect authenticity from everyone in the organization.

It’s better to not have values than to pretend having them. People will make rational peace with the realities of any environment and content themselves with value-maximizing in that environment as defined. But when you trick them into buying in only to find your value system cheap, hollow, and easily melted, they will feel emotionally betrayed. You will lose people, starting with those who are value-driven, when the truth bares itself.

Written partially on behalf of my friends who work for Amazon and are contractually precluded from public honesty about their employment conditions.

TC is a former Amazon ops GM with three decades of leadership experience. He is also a retired USAF Lieutenant Colonel and combat commanding officer with graduate degrees in law, strategy, and organizational management.

Hey TC,

Nice to see your thoughts again.

Bummer Dude... sad to hear that Amazon took such a turn, but it definitely looks like personal growth is still something you can take from the experience.

I was sharing with a friend your comments on when people quit complaining, that as a leader you then have a real problem. Since they've given up trying to improve the situation. I'm sure you recall...

Best of luck

Adam Pearsoll

TC,

Thanks for being brave and courageous to post your experience and thoughts. Many people don’t understand the courage behind speaking truth to power, especially at Amazon, but you and I do.

You know where I stand and my Amazon experience. Great people, energetic and inspiring junior leaders learning and growing how to lead and manage people. However, at the GM and Regional level, the level of ‘save your ass’ at whatever cost and sell out those under you to meet numbers at any cost is tragic. The definition of toxicity to me is changing your values when you succeed, lead by tyranny, so you can keep getting promoted . I came out not convinced the core values were really true….smoke and mirrors . Shame. And I was not the only one….

What I have learned from leaving and working a different sector is that you can get back to your passions and you can get back to your values of serving something bigger than you that values you as a human and a talent. And your health will thank you! :)

Keep moving the needle my friend! Understand and appreciate the people you impacted in the right way…they will remember you (and continue to have you mentor them) well beyond Amazon! I am loving proof. All the best TC